View this page in: English | Español

La audición es compleja y requiere de una serie de acciones y reacciones para funcionar. El proceso implica que muchas partes del oído trabajen juntas para convertir las ondas sonoras en información que el cerebro comprende e interpreta.

Las ondas sonoras ingresan al canal auditivo y viajan hacia nuestros tímpanos.

Las ondas sonoras hacen que vibren el tímpano y los huesos del oído medio.

Pequeñas células ciliadas dentro de la cóclea, el órgano sensorial del oído, convierten estas vibraciones en impulsos eléctricos que son captados por el nervio auditivo.

Al nacer, cada oído típico tiene alrededor de 12.000 células sensoriales, llamadas células ciliadas, que se asientan sobre una membrana que vibra en respuesta al sonido entrante. Cada frecuencia de un sonido complejo hace vibrar al máximo la membrana en una ubicación determinada. Debido a este mecanismo, escuchamos diferentes tonos dentro del sonido. Un sonido más fuerte aumenta la amplitud de la vibración, por eso escuchamos el volumen más alto.

Las señales enviadas al cerebro desde el nervio auditivo se interpretan como sonidos.

Cómo funciona la audición (tiene disponible subtitulado en español)

Una vez que las células ciliadas del oído interno se dañan, se produce una pérdida auditiva neurosensorial permanente.

Actualmente, la pérdida auditiva neurosensorial no se puede restaurar en humanos, pero los investigadores de la HHF están trabajando para comprender mejor los mecanismos de la pérdida auditiva, y así encontrar mejores tratamientos y curas.

Traducción al español realizada por Julio Flores-Alberca, enero 2024. Sepa más aquí.

More Resources

I made one hat to solve problems, never imagining how many other adults and children would relate. It’s an honor to be able to give something back to the cochlear implant community that understands this journey so well.

These findings suggest that the ability to integrate what is seen with what is heard becomes increasingly important with age, especially for cochlear implant users.

Tinnitus Quest’s Tinnitus Hackathon prioritized active problem-solving, cross-disciplinary debate, and the development of a shared research agenda.

As the first known Black author to publish a 10-book children’s series centered on deaf, hard of hearing, and disabled heroes, I’ve created what I once longed for: stories where children see themselves as powerful.

Social platforms have become spaces to compare symptoms, crowdsource explanations, and seek community. For tinnitus, that openness has helped many people feel less alone. Unfortunately, it has also created space for confusion, misinformation, and discouraging myths that can delay effective care.

Often these surprising sources of loud sounds come about from a misguided belief that loud means fun—the louder it is, the more festive. The good news? Because the decibel scale is logarithmic, turning it down even a little can help save our hearing a lot.

When thinking about exposure to loud sounds, it is important to take a life-course perspective. That is, the health behaviors developed in childhood and adolescence can shape habits into adulthood.

I know the only way I could hear it is if we all stopped playing and moved up to the net every time someone has something to say.

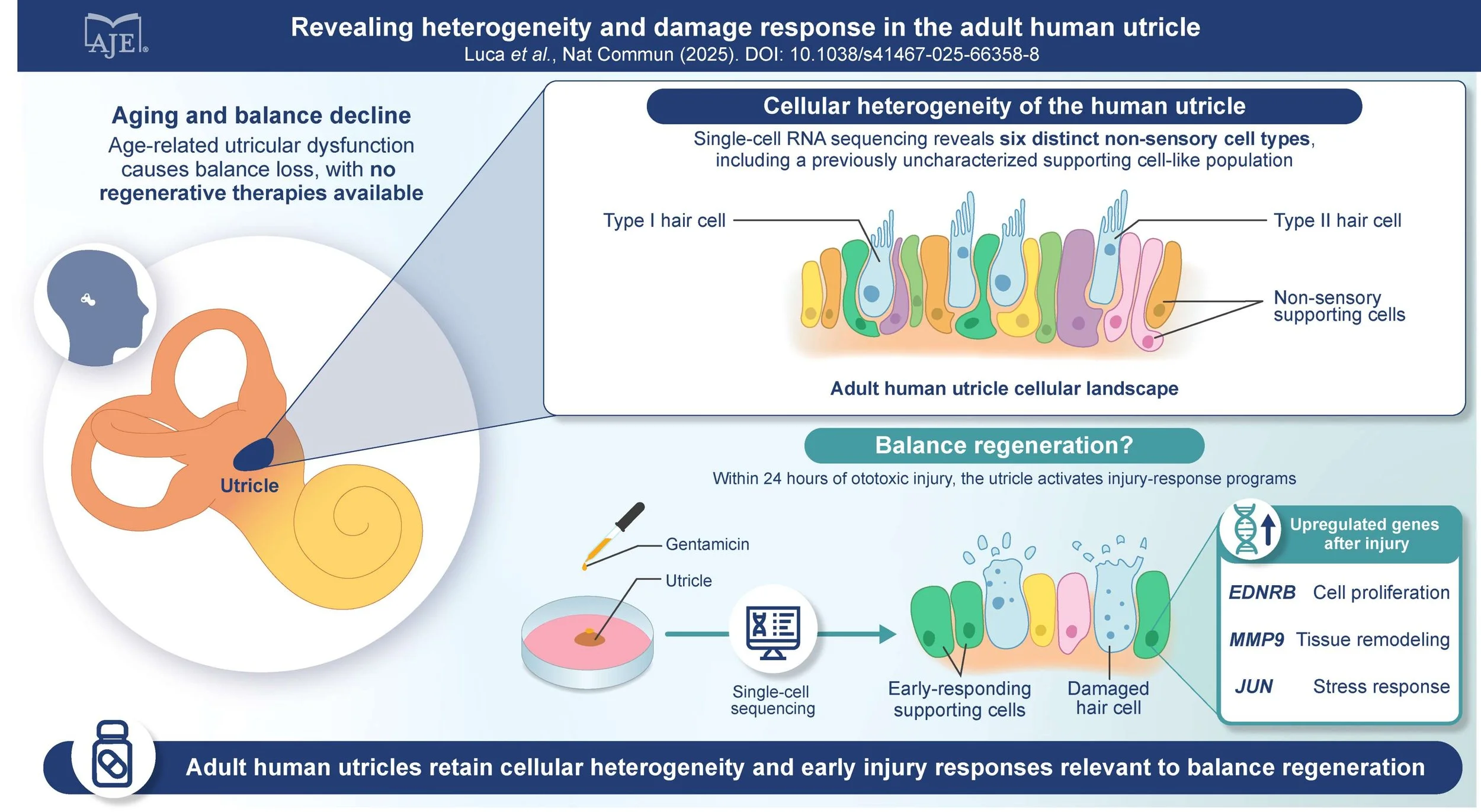

The team’s analysis uncovered a surprising diversity of supporting cells, the “non-sensory cellular guardians” that surround and protect the sensory hair cells and may facilitate their regeneration

It seems paradoxical that a hearing condition intended to work against me could give me the power to truly understand music, but this battle has taught me more about positivity and hope than any motivational speech could.

Because noise-canceling earbuds are so comfortable and block everything out, people wear them for three, four, five hours straight without realizing the cumulative effect on their ears.