By Stefan Heller, Ph.D.

CURRENT INSTITUTION:

Stanford University

EDUCATION:

Studied Biology at the University of Mainz, Germany

Ph.D. at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt, Germany

Postdoc at The Rockefeller University, New York, NY

We are grateful for your interest in Hearing Health Foundation (HHF). Through Spotlight On, HHF aims to connect our supporters and constituents to its Hearing Restoration Project (HRP) consortium researchers. We hope this feature helps you get to know the life and work of the leading researchers working collaboratively in pursuit of a cure for hearing loss and tinnitus

What is your area of focus?

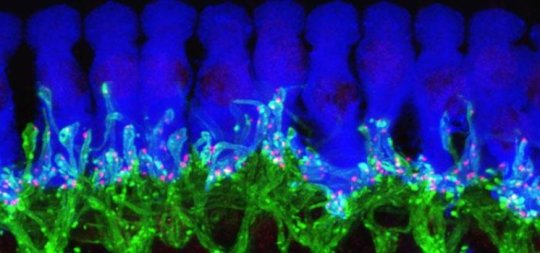

My laboratory seeks to understand how a small patch of embryonic cells forms the inner ear, particularly the sensory hair cells of the cochlea and vestibular organs. We are also very interested in the biology of supporting cells, which in chickens have the ability to regenerate lost hair cells. Another research interest of ours is the use of stem cells to generate inner ear cells “from scratch.”

Why did you decide to pursue scientific research?

As a kid, I convinced my parents to buy me a chemistry lab kit. On numerous occasions the basement needed to be evacuated because of nasty fumes that filled the room. This experience probably gave me an edge when studying science in school, where I had encouraging teachers who inspired interest in neuroscience and genetics. I realized that science provides an endless playing field to connect basic discoveries to the development of useful applications.

Why hearing research?

Serendipity! My Ph.D. thesis focused on how nerve cells are affected by so-called neurotrophic factors. This field of research was popular in the early 1990s because it promised to lead to cures for disorders such as ALS, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s. With many researchers already working on finding cures for these conditions, I believed a cure was right around the corner and I’d be out of a job quickly. So I looked for a new challenge and found the laboratory of Jim Hudspeth, an HHF Emerging Research Grantee in 1979 and 1980, whose research focuses on inner ear hair cells. Five minutes with Jim and I was hooked.

What do you enjoy doing when not in the lab?

I enjoy renovating our family’s 65-year-old midcentury modern house one step at a time. After 10 years, I am about half done. I also enjoy camping trips with my wife and dog; we like hiking and being off the grid to recharge our batteries.

If you weren’t a scientist, what would you have done?

I’ve always felt that research is the best fit for me. I like modern architecture, and although I am not necessarily talented in drawing, I might have liked to do something in that field.

What do you find to be most inspirational?

Interacting with creative people and living in the Bay Area, a region where innovation is cherished and rewarded. All of my mentors have one important trait in common, and that is generosity. They were generous in volunteering their time to discuss wild ideas and scientific problems, giving me resources to explore and experiment. I try to apply this principle to my laboratory group as well.

Hearing Restoration Project

What has been a highlight from the HRP consortium collaboration?

The most valuable aspect of the HRP is that we get together as a group and talk about experiments, approaches, and the problems at hand. There are not many researchers focusing on hearing restoration, so bringing them together frequently is very helpful. We meet twice a year in person and once a month via conference calls, which is optimal for fruitful discussions. Having unlimited access to this talented group brings a lot of value.

How has the collaborative effort helped your research?

Without the HRP, I would not have started to focus on chicken hair cell regeneration. The collaborative approach, made possible through funding from HHF, has helped us to implement novel tools and the latest technology. Combining resources and technologies strengthens our research and expedites projects that help us reach our goal to find a cure for human hearing loss and tinnitus.

What do you hope to have happen with the HRP over the next year? Two years? Five years?

I envision that we will have started to fill in some of these missing components and that we have identified ways to reactivate hair cell regeneration in the mammalian cochlea. I also hope that people connected to the cause, such as individuals living with hearing loss and HHF’s generous supporters, remain patient, because science takes time in order to reach a desired result. We are working on a very complicated problem, and with each new discovery we find new roadblocks that need to be eliminated. I dream of the day when these roadblocks are all gone and we do not encounter new ones. This will be the day we realistically can expect a cure.

What is needed to help make HRP goals happen?

Ongoing funding. HHF is currently supporting research projects at a dozen laboratories, and increased funding per laboratory would allow for even more research to be conducted. HRP researchers benefit from sharing knowledge and small collaborations, but I feel that large-scale concerted efforts and sustained funding are essential to make the HRP’s goals a reality. Hopefully one of the currently funded, small-scale, concerted collaborations will lead to a “eureka” moment that will allow us to leapfrog directly to testing new drugs. Finally, patience is a must! Combined, all of the laboratories working on finding cures for hearing loss and tinnitus totals fewer than 500 researchers worldwide. It is a small field with limited resources, but I am very encouraged about the progress we’ve made so far.

Empower the Hearing Restoration Project's life-changing research. If you are able, please make a contribution today.