By Nadine Dehgan

Aboard my noisy flight to the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) Convention in June, I couldn’t help but reflect upon loud sounds—and what can be done to reduce our exposure.

I’d recently learned that the word “noise” is derived from “sea sickness” or “nausea” in Latin. Noise has literally been associated with poor health outcomes for thousands of years.

Synonyms for “loud” include “ear-splitting” and “deafening.” In fact, vibrations from loud noises travel through the eardrum to reach our inner ear, where sensory hair cells change them into electrical signals to be interpreted by the brain. Hair cells, however, come in limited supply. Humans are typically born with 16,000—and when these cells are damaged by noise, age, ototoxic drugs, or other factors, the brain’s ability to communicate with the ears is significantly weakened, resulting in permanent hearing loss.

Concerned about my fellow plane passengers’ hair cells, I opened my phone’s decibel (dB) measuring app, which indicated the maximum noise level after takeoff was 92 dB, while the average was 83 dB. The app also pointed out that this dB level is equivalent to that of alarm clocks. While this doesn’t seem uncomfortable, it’s actually not recommended for periods over two hours. I’d come prepared with both earplugs and noise-canceling headphones—which I limit to 60 percent of maximum volume in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommendation. But not everyone taking flights comes prepared for the dangerous levels of noise inside the plane.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) states noise greater than 75 dB can harm hearing, and in 1974, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommended that sound exposure should remain at or below 70 dB to prevent noise-induced hearing loss. Sudden loud noise—such as from blasts, gunfire, firecrackers, and bullhorns—also can cause hearing loss with levels reaching 165 dB! This is why so many veterans return with hearing loss and tinnitus. Tragically, they are the two most common disabilities for those who serve.

And yet our society glorifies noise. Two confessions explain my frustration. The first is I love to listen to love songs from the ’90s and my children think these songs are current hits. My second is when my kids are not in my car I often listen to classical music, but once in awhile I listen to current hits. One station’s tagline actually is “Ear-Popping Music.” I couldn’t believe that damaging eardrums was being advertised as a good thing! My youngest daughter, Emmy, had many eardrum ruptures—from infections, not noise—and she truly suffered. My anguish as a parent watching my baby and then toddler in pain was nothing compared to the pain she endured with no understanding of why.

How can we be okay with hearing loss and ear damage advertised as a positive experience? No one would advertise skin cancer from excessive sun exposure as a perk of a beach vacation. Nor would a beverage manufacturer tout soda’s negative impact on dental health.

It is my wish that one day we take the real risk of hearing loss seriously and recognize it for the epidemic that it is. Experts say approximately one in five American children will have permanent hearing loss (largely noise-induced) before reaching adulthood. University of Ohio scientists report that even mild hearing losses in children can cause cognitive damage that would typically not occur until at least age 50. This is horrifying.

Still, we surround our children with damaging noise. Birthday parties, movie theaters, weddings, and family celebrations can blast noise exceeding 115 dB. Football stadiums, hockey arenas, exercise classes, and music concerts have clocked in at over 140 dB, which can cause irreversible hearing loss—whether sudden or progressive damage—in minutes.

Recently, a friend told me she complained of high noise levels (105 dB) to her daughter’s dance studio. Instead of offering to turn down the volume, management told her that she could leave the class. While her daughter can no longer attend dance class, my friend has the consolation of knowing her child is safer. My thoughts go to the employees of fitness centers, stadiums, restaurants, bars, and other commercial establishments whose ears are constantly assaulted.

Before becoming CEO of Hearing Health Foundation (HHF), I didn’t appreciate the dangers and consequences of loud sound. I now know that even a mild untreated hearing loss can lead to social issues including isolation, depression, and poor academic performance in children. In adults, the stakes are also high, with untreated hearing loss bringing the risks of mental decline, falls, and premature death.

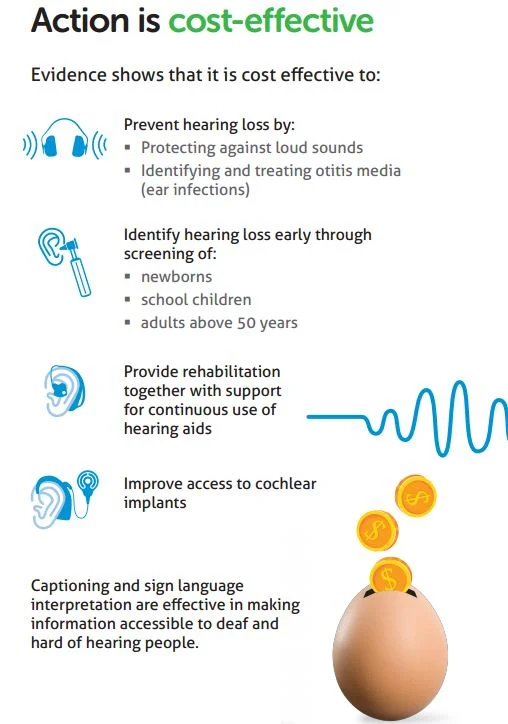

Hearing loss can be mitigated by technology including hearing aids and cochlear implants. While these treatments are beneficial and life-saving, HHF is funding research toward permanent cures. Birds, fish, and reptiles are all able to restore their inner ear hair cells once damaged—but mammals including humans cannot. HHF funds a consortium of top hearing scientists through our Hearing Restoration Project (HRP) who study how other species are able to regenerate their hearing in order to apply this knowledge to humans through a biological cure.

As the plane descended toward Minneapolis, my ears popped, but I know the minor discomfort can’t compete with what Emmy experiences. As the mother, sister, daughter, and granddaughter of individuals with hearing loss, I remember my two biggest wishes: for society to place a greater value on hearing protection, and for HHF to continue to support researchers on their quest to treat and cure hearing loss and related conditions.