Many in the hard of hearing community are primarily verbal communicators. But most communication access plans fail this majority, who do not use sign language or use it fluently. Here, two self-advocates—both late-deafened, both hard of hearing—share examples and their lived experiences to help illustrate what inclusion truly looks like.

By Tremmel Watson and Chelle Wyatt

The phrase “Deaf and hard of hearing” is often used as if it describes a single, unified community. But for many hard of hearing (HoH, or HH) individuals, that label doesn’t reflect our reality.

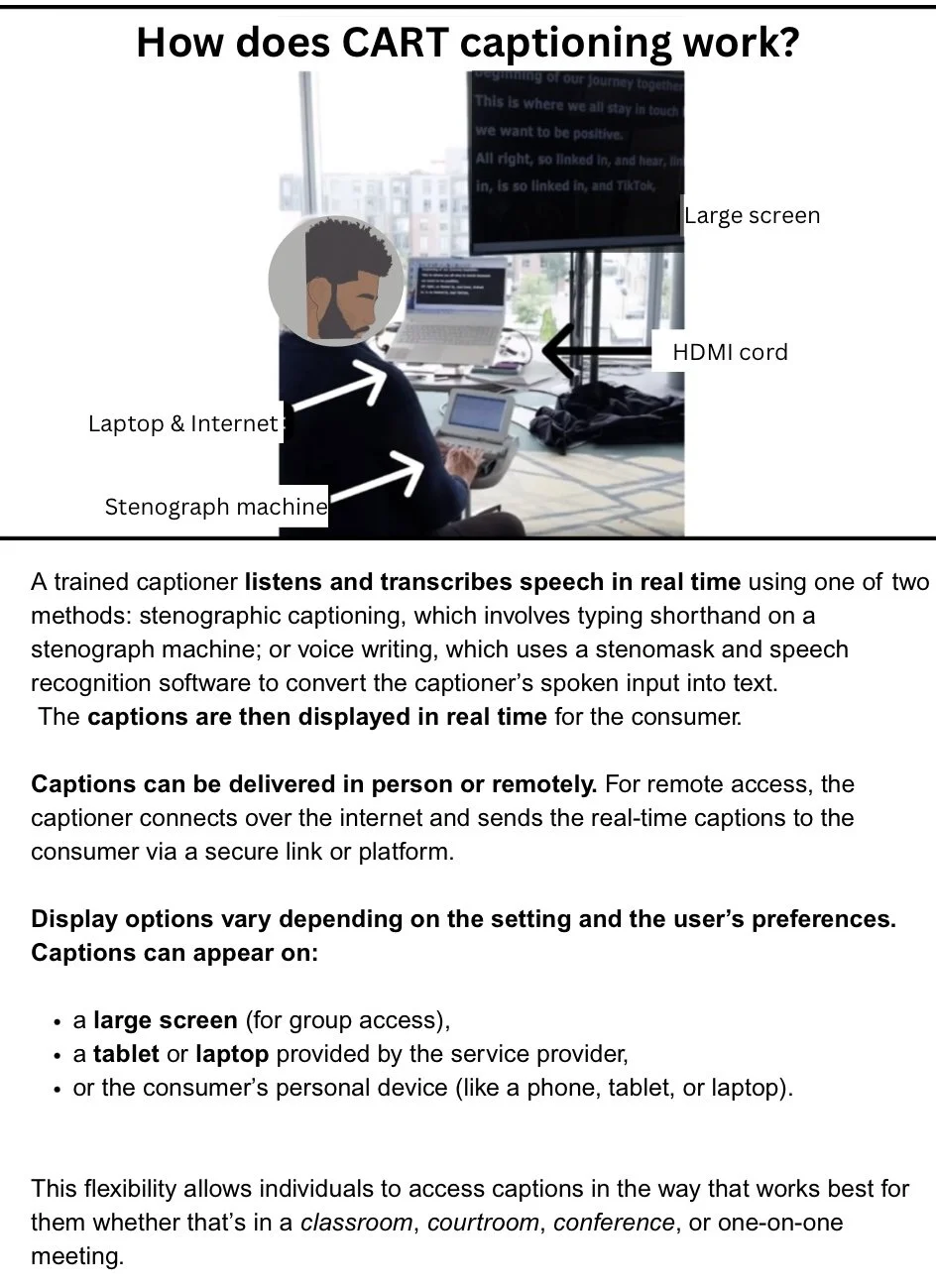

We don’t use sign language as our primary mode of communication. We rely on spoken language, lipreading (speechreading), hearing loops, captions, CART (Communication Access Realtime Translation), and hearing technology.

Even within the d/Deaf and HoH umbrella, our access needs and identities vary widely. That in-between space can feel like nowhere—not “hearing enough” for the hearing world, not “Deaf enough” for Deaf spaces.

Our Hearing Loss Journeys

Tremmel: I lost my hearing in early childhood, after learning to speak. I didn’t grow up with American Sign Language (ASL) or Deaf culture. I relied on lipreading and using spoken language, and eventually relied on captions and CART. That’s why I identify more closely with the hard of hearing (HoH) community than the culturally Deaf community. I’m not transitioning to Deafness. I’m not in limbo. This is my identity.

Chelle: I started to lose my hearing after scarlet fever at 14 years old. It showed up as hidden hearing loss, then it slowly progressed with a few big drops over time. For years, I got by with hearing aids and assistive listening technology—then it dropped into the severe range which changed everything. With that drop in hearing, I lost my job and shied away from social interaction.

Thanks to a few HoH community support systems, I slowly learned how to communicate and participate in society in a new way. This included services like CART. It also meant I had to step out of my comfort zone with a new level of advocacy and get comfortable with educating others about my new communication needs.

Tremmel: When I lost my hearing in prison, I wasn’t met with care. I was met with suspicion.

Instead of being accommodated, I was put through a series of invasive tests just to be believed. One of them was the ABR (auditory brainstem response) test. They attached electrodes to my head to measure my brainwaves and decide if I was “faking.”

It didn’t stop there. Interpreters were allowed to deny me services if they felt I wasn’t “fluent enough” in sign language. If I didn’t meet their standard, I was denied access to basic information, programs, and support.

I’ve had sign language interpreters be dismissive. I’ve been made to feel like I wasn’t welcome because I preferred CART over interpreters. But I wasn’t being defiant. I was choosing my primary language, English. I can use ASL well enough to hold a conversation, but that doesn’t mean I’ll understand everything the other person is signing. That’s why captions work better for me. CART gives me full access without the guesswork.

People May Make Assumptions

Chelle: For personal one on one conversations, I tell people I use lipreading so they need to face me when talking. Unfortunately, many people tend to jump to the conclusion that I’m part of the Deaf community and use ASL.

Once medical staff ordered an ASL interpreter based on that assumption, without asking me if that was my preference. When the interpreter showed up, I was shocked. Although I know enough ASL to get by, I’m in no way fluent enough to follow interpreters. They didn’t think to offer CART, which would have given me the most benefit.

In many spaces, ASL is treated as the default accommodation. But fewer than 500,000 people in the U.S. use ASL as their primary language. That’s less than 1 percent of the 50 million Americans with hearing loss. One of the most common misunderstandings is the assumption that all deaf or hard of hearing people use sign language. That simply isn’t true.

The Diversity of Hearing Loss

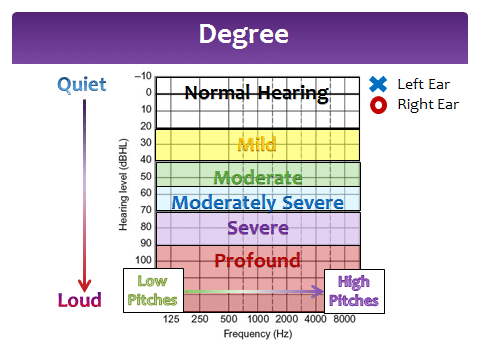

Credit: Arizona Hearing Specialists

Chelle: There’s a spectrum to hearing loss. It varies by degree, type, and how it affects a person’s ability to process sound. Medically, hearing loss is categorized by decibel loss: mild, moderate, severe, and profound.

Hearing loss can be high frequency, reverse slope, and cookie bite—all referring to how the audiogram results appear. It can be conductive (middle ear), sensorineural (inner ear), or a combination of both.

It can come early in life or later in life. It can happen suddenly and or as a slow progression.

Everyone’s hearing loss is individual and each one affects the sounds of speech differently. This is why the HoH have different needs and use different labels.

Some people sign fluently. Others never learned. Many rely on a mix of tools like captions, CART, hearing aids, lipreading, and hearing loop systems. Our communication preferences aren’t based on assumptions. They reflect our lived experience.

These preferences are not fallback options. They are essential access tools for many of us. When we’re forced into ASL-only spaces, we’re not being difficult by asking for captions or assistive listening. We’re asking for what actually works.

Respecting Identity

Tremmel: Something else I’ve learned from moving through different disability spaces is that language varies. I’ve met people who still self-identify as “hearing impaired” or use other terms that aren’t widely preferred in advocacy circles. And that’s okay. People have the right to describe their own experience in the language that feels true to them.

That said, there are guidelines we try to follow. “Hearing impaired” is generally discouraged when referring to D/HoH people unless they use that term for themselves. It’s about respect and it’s also about meaning. The term “hearing impaired” reduces us to a problem that needs fixing.

Being hard of hearing isn’t about what’s missing; it’s about how we experience the world. Terms like “deaf” and “hard of hearing” honor who we are without framing us as broken. Language matters because it shapes identity, self-worth, and pride.

Not everyone has access to the same education around identity and terminology. Not everyone has been in rooms where those conversations happen. And that doesn’t make them any less part of this community.

This chart shows how assumptions about ASL fluency can block access.

When I talk with people about language, I try to share information without correcting from a place of superiority. I’m self-educated, and I’m still learning. I believe in meeting people where they are. You can teach without making someone feel small. That’s how you build real connection and lasting change.

I always say the hardest part of self-advocacy is the education piece. It takes grace, but also the ability to be clear and direct. I often find myself explaining to event organizers or healthcare staff how to request CART. In my experience, many sign language interpreter agencies also offer CART services, which surprises a lot of people.

So I usually tell organizers that if they know how to request an ASL interpreter, start there, and then ask that same provider if they also offer CART. I also explain that I became deaf later in life, and that captions are the most effective form of communication access for me.

We see “D/HH” on flyers, grant applications, and conference agendas. But when it’s time to deliver access, it’s often ASL-only. CART isn’t offered. Captions aren’t considered. And we’re expected to be grateful just for being named.

Building Power and Visibility

Chelle: While hearing aids and cochlear implants help, true rehabilitation goes beyond hearing devices. Most people with hearing loss are given hearing aids without learning their limits. Hearing devices help but they don’t fix the loss or give us back natural hearing abilities. They work best within 6 feet and though better than ever, background noise still interferes with speech.

Because people aren’t aware of the limits, family, friends, colleagues, and the wider general public have unrealistic expectations about our hearing devices. They don’t know they need to make some changes in communication habits as well.

To be truly successful with hearing loss, people need to learn how to self-advocate and navigate the hearing world with accommodations to fill in the gaps. After learning how to manage a severe hearing loss in public, I took it as my mission to help others with hearing loss do the same.

That is why I teach lipreading classes through Hearing Loss LIVE! Lipreading has several misconceptions as well, such as we lipread every word. That’s not true. We fill in the gaps with several other strategies.

And lipreading doesn’t always work depending on many obstacles. For this reason, we teach people to advocate for additional accommodations in our classes like CART, other technologies, and assistive listening. Most lipreading students don’t know they have access to public events in this way. More awareness is needed.

Our Recommendations

Let’s start with policies. Here are our suggestions:

• Require dual accommodation planning: ASL and CART/captions

• Fund captioning services at the same level as interpreting

• Include HoH representation in access planning and disability advisory boards

The Deaf community built their culture and power through decades of organizing. It didn’t start with full recognition. It started with connection, visibility, and collective action.

The HoH community deserves that same path. We may not have a shared language, but we have shared experiences. We deserve to define ourselves. People need to learn to listen to—and respect—our communication choices.

Tremmel Watson is a disability advocate and consultant with experience in assistive technology based in Sacramento, California. Contact him at tremmel.watson@disabilityrightsca.org.

Chelle Wyatt lives in Salt Lake City, Utah. She supports hearing loss awareness through her business, Hearing Loss LIVE! and through volunteering with local and national hearing loss support groups.

Graphics except where noted are courtesy of, or adapted from, Disability Rights California.

These findings suggest that the ability to integrate what is seen with what is heard becomes increasingly important with age, especially for cochlear implant users.