A practical reference, not a lecture, from a music industry professional on how to protect our first instrument: our hearing.

By Alexander Wright

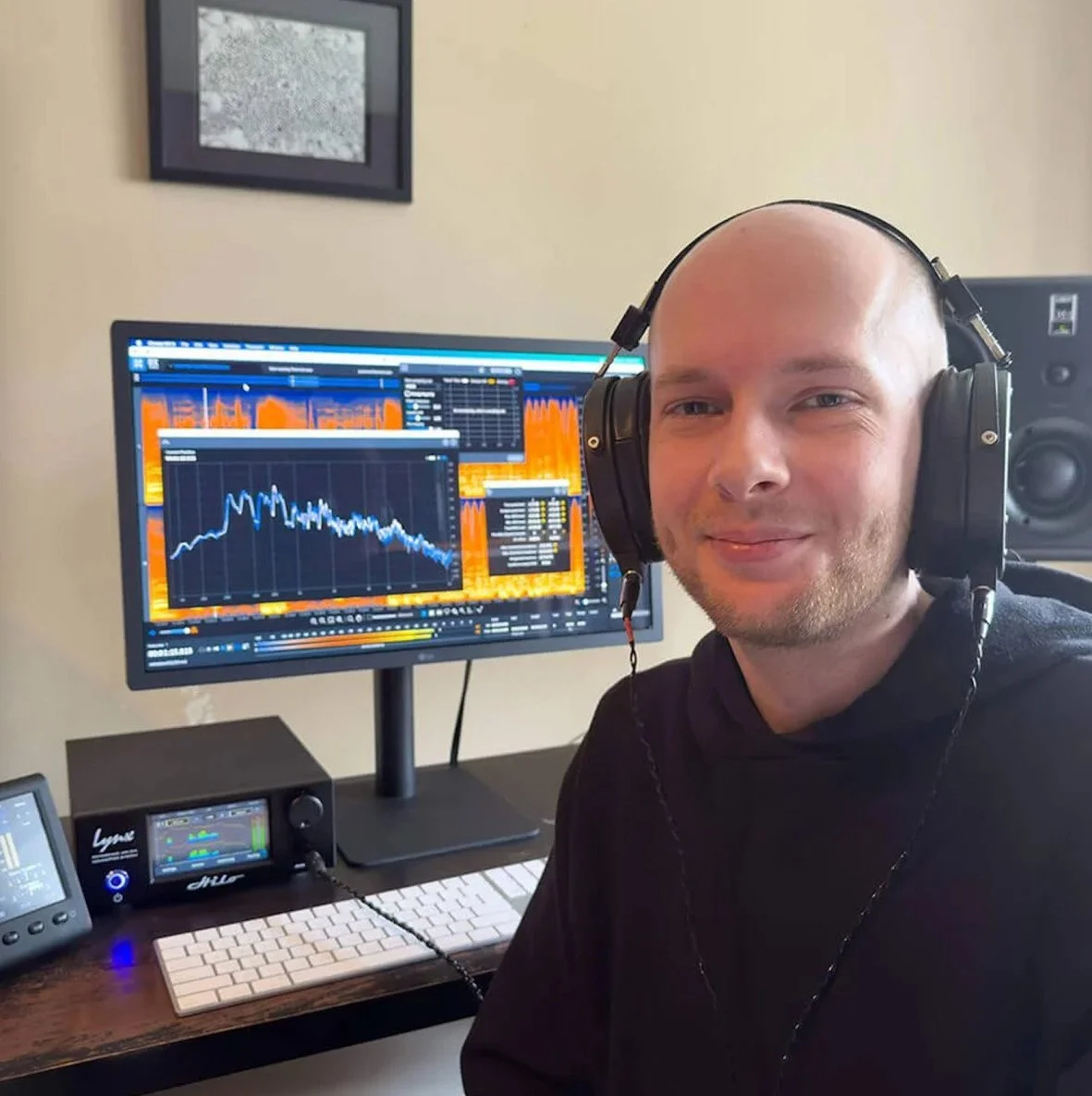

Alexander Wright is a Berklee-educated mastering engineer who shares healthy hearing tips for other music industry professionals on his website.

I’m an independent mastering engineer in Seattle. I work full-time with artists, mixers, and producers, and I also write and teach about perception, hearing health, and safe listening for musicians and audio folks.

I’ve recently added Hearing Health Foundation to my monthly giving and have started pointing my audience to HHF as a solid, research-driven resource on hearing loss and tinnitus. I like to be sure I’m aligned with current evidence when I talk about prevention.

I first became aware of the impacts of hearing health after seeing my father experience profound hearing loss. He saw AC/DC in pubs back in Australia and Led Zeppelin in ’74—needless to say he’s a music lover who can no longer hear much at all.

We have had some discussions about his regret and sadness at no longer fully hearing the music he loves. His experience motivated me to take care of my hearing, especially as a music professional myself.

After growing up on the Mornington Peninsula outside Melbourne in Australia, I arrived at Berklee College of Music in Boston thinking everyone would be wearing earplugs, only to find out that (to this day) very few are, and the education around it was lacking.

One professor, mastering engineer Jonathan Wyner, told us, “We work in music, so our first instrument is our hearing.” I’ve learned that everything else—gear, taste, translation—sits on top of that.

Why Our Risk Is Higher

As music professionals, we spend more hours around loud sound (rehearsals, gigs, headphones, studio). We also need to be able to hear more subtleties in sound than the average person in order to do our work.

But hearing damage is cumulative and irreversible. Once we lose the fine detail, we’re mixing and mastering around a permanent bias. This is potentially career-ending.

There are U.S. workplace regulations that require a hearing conservation program at 85 dBA for an eight-hour average workday (“dBA” refers to decibels adjusted for human hearing) and that set a legal permissible exposure limit of 90 dBA for an eight-hour day.

However, these limits were written to stop factory workers from ending up obviously deaf, not for preserving a mastering engineer’s ability to hear nuances. (The 40-hour work week also doesn’t take into account our 24/7 sound exposure.)

So for music professionals, these workplace limits are outer boundaries.

Daily Habits

Along with hourly 10-minute rests in quiet, during his workday Alexander aims for 70 to 80 decibels—with 80 dB a ceiling, not a target.

During most of my workday, I aim for roughly 70–80 decibels and treat 80 dB as a ceiling, not a target. This is comfortably under “fun loud” (which I put in quotes, because fun does not mean dangerously loud!).

In rehearsals or clubs, or if I need to physically be by the stage, it can easily hit 95–100 dB. This is brief, protected time—earplugs in, breaks in quiet, and not living there for hours.

When we need to be close to the speakers or snare drum, or anything that feels physically aggressive, this is in the 110-plus dB world. Safe exposure is measured in minutes or even seconds.

For quick checks, I use the NIOSH Sound Level Meter app, iOS only; the app Decibel X is also on Android. But there are clues that require no gear. If I have to raise my voice at arm’s length to be heard, I know my dose clock is running fast. If I step outside and the world sounds muffled or I hear a new ring, that was an overdraft on tomorrow—I know I need to pay it back with quiet and sleep.

I treat fatigue as data. If my top end feels “soft” by late afternoon most days, that’s my system asking me to do less, not to turn up more. I take real breaks in quiet, with a timer, 10 minutes per hour. This is not laziness; it’s maintenance.

Earplugs 101

We should all wear plugs we can live with and keep them in every jacket and coat pocket, bag, drawer, glove compartment, instrument case. Don’t be a hero. “I’ll just do this one song unprotected” is exactly how exposure sneaks up on us.

Foam plugs are cheap and effective, but they distort sound and muffle high frequencies. These are better than nothing but best as backup.

Universal (non-custom) musician plugs are inexpensive, provide reasonably flat attenuation, and reduce volume more evenly across frequencies, so the music stays clear.

Custom musician plugs are the adult move. These are molded to your ears, with interchangeable filters that cut 9, 15, or 25 dB to lower sound intensity without losing clarity. Comfortable for long gigs and full rehearsals and shows, they’ve never reduced my enjoyment of live music.

Custom in-ear monitors are molded earpieces that both isolate external noise and deliver a personal mix directly to the ears. That sound isolation allows me to run quieter, not louder.

I always have two plug options on my person, and I seat them properly—deep, snug, inserted with jaw relaxed. A half-inserted plug is almost only cosmetic.

Live Reality

This is where most industry players take the biggest hits. When I work with bands, I measure rehearsal once using the NIOSH app for a couple of songs. Knowing whether our room sits at 92 dB or 100 dB changes how we plan.

I insist on lower stage volume. Guitars, keys, wedges—if we can get everyone to cooperate and knock the stage down even 3–6 dB, our ears and the front of house both win.

I plan quiet days after loud ones. I follow festivals, double-sets, or long studio days at higher sound intensities with lighter listening days for recovery.

We can frame this in sound terms: “If we pull this down a bit and everyone wears plugs, we’ll actually hear one another and tighten up.” People will often do more for better sound than for “health!”

Originally from Australia, Alexander lives in Seattle with his wife Maya and their dog Ozzy.

And Finally

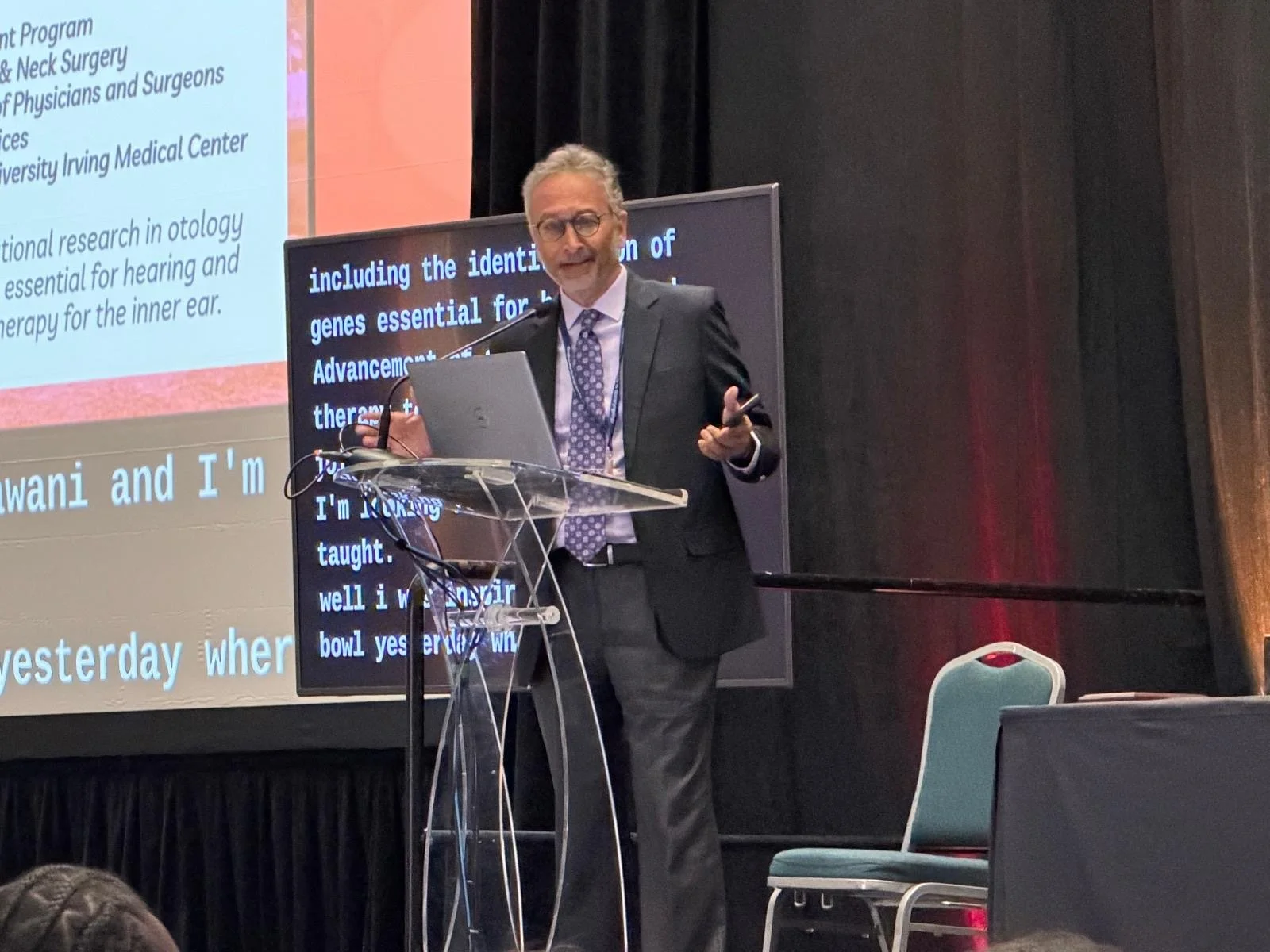

Get a baseline audiogram with an audiologist who works with musicians. I repeat hearing tests on a sensible cadence: every year or two, more often if there’s something to worry about, like any persistent ringing, specific frequencies that feel off, unusual sensitivity. I look for trends in the hearing test results, and treat my ears as part of the monitoring chain, not an invisible constant.

Tinnitus is extremely common in our world. A new, clear, persistent ring after loud exposure is a warning. Many short-term spikes do settle with quiet, sleep, lower total sound, and lower stress. The key is to stop giving our ears more to deal with while they recover. Intrusive, ongoing tinnitus deserves a proper look by an audiologist.

Pick a simple north star—for me, I want my hearing to still feel usable for creative work at age 70—and let that inform the boring choices: plugs, breaks, slightly lower monitor levels, the odd quiet day.

This is not medical advice; it’s the working practice of a music professional. The sounds we create tomorrow depend on the care we give our ears today.

Alexander Wright is a mastering engineer who works with artists, mixers, and producers around the world from his studio in Seattle. For more, including additional resources, see alexanderwright.com.

The internship last summer provided my first real chance to step into hearing science and learn the experimental side of speech perception under the tutelage of a senior researcher.