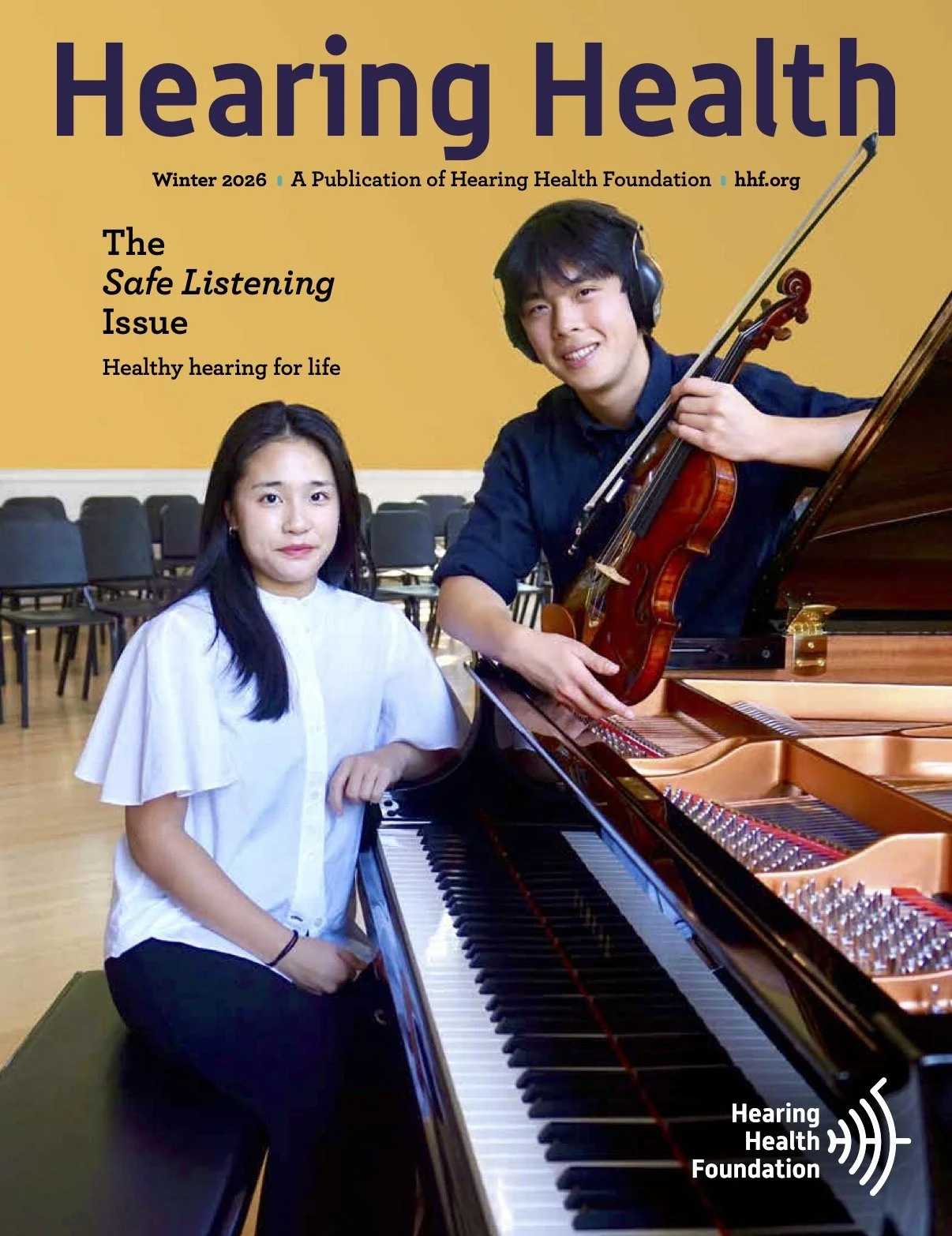

When wearing earplugs earns a reprimand from a master teacher, two high school classical musicians decide it’s time to change the conversation about the risk of hearing loss among their peers.

By Khaos Kook and Kaitlyn Gia Lee

Introduction by Sharon Kujawa, Ph.D., Hearing Health Foundation Board Member and Scientific Trustee:

High school students Khaos Kook and Kaitlyn Gia Lee originally contacted me in relation to their efforts to better understand risks to hearing from sound over-exposures. As classical musicians with years of exposure accumulated through near-daily practice, rehearsals, and performances, they had already done a huge amount of self-directed study of hearing and hearing loss prior to our first meeting. They had a good appreciation of possible consequences of loud sound exposure and expressed their desire to educate their peers, who they believe underappreciate their hearing loss risks.

We have subsequently met on a regular basis to discuss these issues and review the existing literature. These remarkable and very talented students have now undertaken a project with both research and educational components in which they aim to test their hypotheses about hearing status, attitudes, and practices of young musicians and non-musicians and to educate them about hearing-related risks of loud sound exposure.

As these young individuals will have no shortage of opportunities for such exposures over the course of their lifetimes, the activities undertaken by Kaitlyn and Khaos have the potential to result in positive hearing health outcomes.

Khaos: Standing Out to Stay Safe

If I possessed slightly more courage and slightly less social abashment, I’d carry a card that reads: “Please excuse my hearing dysfunctions. Protection necessary. Thank you for understanding.” And I, a violinist with tinnitus and hyperacusis, frequently encounter situations calling for such an explanation. After all, have you ever seen a classical musician wear earplugs, then go a step further by also donning industrial-grade earmuffs?

The tinnitus arrived first, settling in during the early months of the COVID pandemic. Initially it was relatively unobtrusive, but the volume and pitch of radio static in my ears grew insistently over the years.

Three years after the onset of tinnitus, hyperacusis also decided to join the onslaught. Over the years, the duo’s irksome clamor has continuously demanded my attention, but I’ve had no inclination to give in.

To protect against these conditions, my mom introduced me to earplugs of the standard plastic variety to wear during practice. Though I’ve now settled on foam earplugs for maximal attenuation, I’ve cycled through enough different kinds of plugs in my five years of usage that opening a secondhand earplug shop on Amazon is an entirely attainable (albeit unsanitary) entrepreneurial endeavor.

However, while the plugs provide some protection and are mostly inconspicuous, the noise reduction they provide is insufficient to mitigate the severity of my hearing disorders. Thus, wearing earmuffs, which suffocate the ears of sound, is my only course of action, even when performing.

In classical music, a deeply unorthodox appearance is one thing, but being ostracized from certain groups as fringe or anomalous is another topic altogether. Most observers simply cannot fathom the reason for donning such obtrusive apparel, especially in a craft synonymous with elegance and class.

And while I have slight consolation that I may be the first classical musician in history to have the gall of performing with earmuffs, critics are often less understanding of such blatant nonconformity.

Kaitlyn: To Listen Differently

Having grown up as a classical musician, I was naturally sensitive to sound. Being immersed in a world saturated with the sounds of music, the idea that they could have damaging effects had never crossed my mind.

Until recently, the only hearing test I ever took was in 4th grade: “Press the button when you hear the beep.” No one since ever asked me to think about my ears as anything but passive recipients of my music making.

It wasn’t until I met Khaos that I saw someone experiencing the flip side of music performance and began to reconsider this ingrained assumption. Watching him play with earplugs and earmuffs forced me to confront a question I hadn’t been asking: What if those passive recipients were not a given?

Only in retrospect have I begun to notice the warning signs that always existed. During solo piano performances with various symphonies, I found myself unable to hear my own passages, played only a few inches away from my ears, over the orchestra’s wall of sound. Instead of listening to the keys, I relied upon muscle memory and pulse, trusting the piano to project toward the audience and my hands to guide themselves onto the correct ivories.

After later talking with Khaos about his conditions and his hearing protection, I considered myself enlightened on the risks of loud sound exposure and hearing health practices. Yet during jazz band rehearsals of “Caravan” (a piece popularized by the film “Whiplash”), I didn’t feel inclined to mitigate the piece’s volume in any way.

As the vibrations pounded through my chest, trumpets blared, drum sets collided in rhythm, and the whole room shook with energy, I thought about the possible detriment being presented to my ears. Maybe some hearing protection was warranted, for all of us in the room. So I looked around: Nobody wore protection, nobody changed anything—so neither did I. Perhaps there are others out there who feel the same: aware of the danger, but unsure how to act, because it feels awkward to be the first one who takes that first step forward.

It almost seems that in the classical music genre, discussion of hearing protection is virtually nonexistent. At least for me, no one has ever bothered to mention anything remotely related. I’ve always thrived as a musician, but I now thrive on the edge of something I can no longer ignore.

Khaos: Inside the Culture

Although some musicians accommodate the usage of hearing protection, a larger proportion seem to take affront on behalf of classical musicianship. On multiple occasions, I’ve been lectured as to why hearing embellishments blight the art of violin and how the best cannot stand for such things.

I’ve also been told to “deal with it like the rest of us,” and even among the more accepting pedagogues, the default response is a variation of “find a more inconspicuous option.” And while this is undeniably better advice than outright denial of protection, earplugs alone no longer provide me adequate protection.

But beyond my personal struggles with industry perception, the most pressing issue is that the majority of young musicians fall into two main categories of hearing health awareness: unaware of any safe listening practices, or vaguely aware but indifferent to action. It is well evidenced that classical musicians are susceptible to much higher rates of hearing loss and related auditory comorbidities, so the general attitude of harsh rejection and inattention to hearing health preservation in this community is troubling.

To provide a further anecdote: I recently attended a masterclass in Europe with violinists in my age group and happened to see a peer wearing earplugs while playing. For context, this is only the second youth musician I’ve ever seen wearing any form of hearing protection. Moreover, I learned that she wore them not for medical reasons, but solely for hearing preservation.

Although our session professor condoned my hearing protection out of necessity, she was not so kind to my earplug-adorned compatriot. After listening to the student’s desire to keep her hearing safe, the professor bluntly said, “Then you would be better off not playing the violin.”

As she is a well-meaning steward of classical music, I am sure the professor meant no harm. However, the discouragement of healthy hearing practices is without a doubt off-putting and deterring for young musicians who are just beginning to take action for their health, especially when such disparagement comes from authority figures.

Music, at its core, is deeply personal. Like any other art, its purpose is to evoke emotions, rouse the pathos of the audience, and communicate. Unfortunately, the moment hearing protection enters the discussion, this exchange becomes secondary. The music itself, which should command attention through distinctive artistry and interpretation, is overshadowed, and we are instead recognized for our deviation from the quintessential image of a classical musician.

Kaitlyn: Too Close for Comfort

Through Khaos, I observed how other musicians reacted to the risks of sound exposure, and it forced me to confront my own complacency about hearing health. The prospect of hearing loss had always seemed so distant and improbable, something that only happened to the elderly. But when you see a peer experiencing a very different reality to music in the same rehearsal room, suddenly the issue becomes real. The contrast in our musical experiences, where Khaos’s had been shaped by auditory conditions, and mine by unfamiliarity, showed me the extent of this divide.

Now that I’ve grown more acclimated to safe hearing practices, I find it both laughable and concerning that I initially forsook my health to avoid social discomfort. In general, Khaos and I have both found this paradigm to be present among those more aware of safe listening practices. What we knew from our experiences gave us a reason to care, and what we didn’t know gave us a reason to investigate.

So, we began to raise questions.

Is it really the case that our hearing is endangered by the sound of our instruments? If so, why is hearing preservation still such an uncomfortable topic in professional musicianship?

Unfortunately, nobody around us seemed to have answers.

Khaos and Kaitlyn: Research and Advocacy

In hopes of unearthing a satisfactory explanation, we turned to the scientific literature on loud sound-induced hearing damage in the classical music community.

Confirming our suspicions, we found a consensus on elevated musician susceptibility to auditory dysfunction, with the majority of players routinely exposed to harmful noise levels. Studies on the relationship between musicians and cochlear synaptopathy, a type of damage undetectable through standard hearing tests, also intrigued us greatly.

Given the wealth of existing research, the stark contrast between such robust scientific understanding and lack of musician awareness is paradoxical. One could reasonably imagine that classical musicians, out of all people, would be among the most ready adopters of hearing health education, considering the importance of proper auditory function in the making of music.

In an attempt to remedy this gap, we formed an initiative to outreach and educate our musician colleagues about this issue, with the goal of providing greater exposure on a topic so crucial to their professions. It wasn’t until we were fortunate enough to obtain Dr. Sharon Kujawa’s mentorship, however, that our hopes of first conducting a research study to lend further credence to our outreach efforts fully crystalized.

Focusing our work on the comparatively less studied population of younger classical musicians, we hope to illuminate any signs of early hearing risk or damage. We also want to encourage a cultural shift within the classical music industry toward greater cognizance and acceptance of safe hearing practices.

The Path Forward

Of course, we are not saying that non-musicians should be any less wary of noise-induced hearing loss and its subsequent health effects. Rather, the point is that even among those partaking in a craft reliant on acute auditory sensitivity, there exists a profound underappreciation of the risks noise exposure creates.

Also consider that music-related exposure is only part of the equation: If the acoustic load from recreational activities is added, the burden is increased. However, the solution need not be radical. Practical steps can dramatically reduce risks with little disruption.

Measures such as mandatory hearing health education in all music programs and institutes, widespread provision of musician’s earplugs, implementation of sound shields, and standards of safe practice in orchestral settings would without a doubt help reshape the culture around hearing preservation in classical music.

The path forward is one of individual and collective effort. Musicians deserve empowerment through continuous exposure to knowledge, rather than being burdened, unknowingly in most cases, by outdated notions of what defines a “proper” musician. The time is ripe to acknowledge that the protection of one’s hearing and the pursuit of musical excellence are not mutually exclusive goals.

High school students Khaos Kook and Kaitlyn Gia Lee live in Seattle. They play the violin and piano, respectively. Their love for classical music led to the creation of the youth-led nonprofit Project CliKK, which focuses on elevating musicianship in communities facing socioeconomic barriers and spreading awareness of hearing health. For more, see projectclikk.com. This appears as the cover story in the Winter 2026 issue of Hearing Health magazine, in mailboxes by the end of January.

The internship last summer provided my first real chance to step into hearing science and learn the experimental side of speech perception under the tutelage of a senior researcher.