Roland Eavey, M.D. (1987–88 ERG), the chair of the otolaryngology department at Vanderbilt University coauthored a report in The Journal of Nutrition on May 11, 2018, that showed women with healthier diets had a lower risk of hearing loss. The healthier diets emphasized fruits, vegetables, fish, seafood, nuts, beans, legumes, and olive oil over dairy, meat, and poultry. The longitudinal study spanning 22 years and including more than 70,000 women showed those with a better eating habits cut their risk for moderate or worse hearing loss by 30 percent. —Yishane Lee

Hearing Loss Lives with Me

By Sonya Daniel

I was born with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. I didn’t know the official term for it until 2008. When I was a kid in elementary school I passed every hearing test that the mothers in the PTA administered. I was a pretty clever little girl. I learned that every test has a visible “tell” and knew how to guess “right” on all of them. I never wanted to fail any test. I learned to read lips, and assumed everyone heard that annoying ringing constantly. That, of course isn’t true.

The tinnitus became too overwhelming to deal with everyday. I hadn’t had my ears tested since I was little, so I didn’t know what to expect. It was much worse than I had ever imagined it would be. And now it had a name. I left the audiologist knowing at some point I’d be completely deaf. But, no one knows when that might be. I was a mother to three young boys. I wondered how much longer I’d hear, “Mommy, I love you.” Or If they’d hold out long enough to hear their grown-up man voices. How much longer until I couldn’t hear music?

Music is my passion. In fact, it’s my chosen profession. I never remember wanting to do anything but be a musician in some capacity. My dad played the guitar. My mother said when I was little I would sit in front of him and touch his guitar and I would stand in front of the stereo and touch the speakers. I suppose I was trying to “hear” the music. I knew I’d go to college and major in music as a vocalist. I knew I wanted to share my love for music and teach others.

College was a very difficult and stressful time. There was a course called “Sight Singing and Ear Training” required to complete my Bachelor’s in Music. I mean, come on! Ear training? I struggled. Professors struggled to teach me. Some never gave up because it was apparent I wasn’t going anywhere.

I did get to teach music to every level. I can’t do that anymore, but I still do music everyday. Sometimes in life you have to know that there are things that your body just won’t let you do. I’d like to be a 6’0” tall, blonde supermodel, too. My body said “no” to that and I think I’m ok.

Living with tinnitus and hearing loss can be overwhelming and difficult. I’m not as afraid of living this way as I used to be. Everyone has a thing. This is just mine. I like to say I don’t live with hearing loss; it lives with me.

My journey has brought me to the cochlear implant. I’m a candidate in the preliminary stages of that process. Technology changes so fast it’s hard to keep up. My current devices have stronger receiver tubes and ear molds.

That’s just my journey with my ears. My life isn’t defined by or consumed with my ears, although it’s felt that way at times. I’m constantly learning and growing. I’m getting stronger with each high and low I face. But, isn’t that just life?

Sonya Daniel is a musician/teacher, writer, and voiceover artist. She is a participant in HHF’s “Faces of Hearing Loss” campaign.

Receive updates on life-changing hearing research and resources by subscribing to HHF's free quarterly magazine and e-newsletter.

Clear Speech: It’s Not Just About Conversation

By Kathi Mestayer

In the Spring 2018 issue of Hearing Health, we talk about ways to help our conversational partners speak more clearly, so we can understand them better.

But what about public broadcast speech? It comes to us via phone, radio, television, and computer screen, as well as those echo-filled train stations, bus terminals, and airports. There’s room for improvement everywhere.

This digital oscilloscope representation of speech, with pauses, shows that gaps as short as a few milliseconds are used to separate words and syllables. According to Frank Musiek, Ph.D., CCC-A, a professor of speech, language and hearing sciences at the University of Arizona, people with some kinds of hearing difficulties require longer than normal gap intervals in order to perceive them.

Credit: Frank Musiek

In some cases, like Amtrak’s 30th Street Station in Philadelphia [LISTEN], clear speech is a real challenge. The beautiful space has towering cathedral ceilings, and is wildly reverberant, like a huge echo chamber. Even typical-hearing people can’t understand a word that comes over the PA system. Trust me; I’ve asked several times.

In that space, a large visual display in the center of the hall and the lines of people moving toward the boarding areas get the message across: It’s time to get on the train. I wonder why they even bother with the announcements, except that they signal that something is going on, so people will check the display.

Radio is very different, at least in my kitchen. There are no echoes, so I can enjoy listening to talk radio while I make my coffee in the morning. The other day, the broadcast about one of the station’s nonprofit supporters was described as: “…supporting creative people and defective institutions…”

Huh? That couldn’t be right. It took a few seconds for me to realize what had actually been said: “supporting creative people and effective institutions.” Inter-word pauses are one of the key characteristics of clear speech. A slightly longer pause between the words “and” and “effective” would, in this case, have done the trick.

In the meantime, I chuckle every time that segment airs (which is often), and wonder if anyone else thinks about the defective institutions!

Staff writer Kathi Mestayer serves on advisory boards for the Virginia Department for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing and the Greater Richmond, Virginia, chapter of the Hearing Loss Association of America.

Simple Treatment May Minimize Hearing Loss Caused by Loud Noises

John Oghalai, M.D. (a 1996–97 ERG scientist), of the University of Southern California, coauthored a May 7, 2018, study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showing promise for preventing noise-induced hearing loss. Using a mouse model, the investigators found that in addition to immediate hair cell death after loud noise exposure, a fluid buildup in the inner ear occurs, eventually leading to nerve cell loss. Because the extra fluid shows a high potassium level, the researchers saw a method to rebalance the fluid by injecting a salt and sugar solution into the ear. Nerve cell loss was reduced by 45 to 64 percent, which the team says may preserve hearing. The team sees future applications for military service members exposed to blast trauma and patients with the hearing and balance disorder Ménière’s disease. —Y.L.

Novel Drug-Delivery Method to the Inner Ear

By Gary Polakovic, USC News

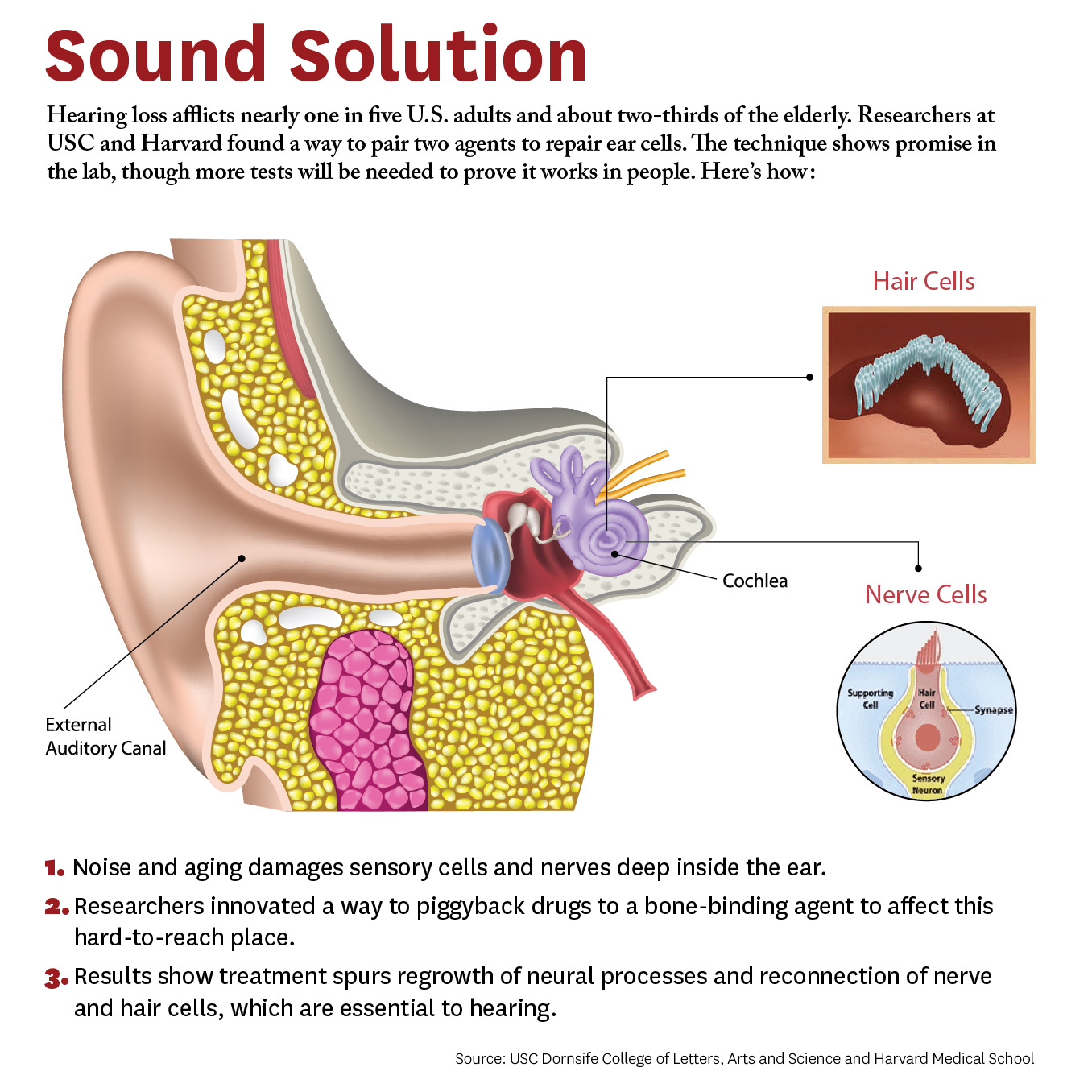

Researchers have developed a new approach to be able to repair cells deep inside the ear. The study, conducted by scientists at University of Southern California (USC) and Harvard University, demonstrates a novel way for a future drug to zero in on damaged nerves and cells inside the ear.

Credit: Matthew Pla Savino/USC News

“What’s new here is we figured out how to deliver a drug into the inner ear so it actually stays put and does what it’s supposed to do, and that’s novel,” says Charles E. McKenna, Ph.D., a corresponding author for the study and chemistry professor at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences.

“Inside this part of the ear, there’s fluid constantly flowing that would sweep dissolved drugs away, but our new approach addresses that problem. This is a first for hearing loss and the ear,” McKenna adds. “It’s also important because it may be adaptable for other drugs that need to be applied within the inner ear.”

The paper was published April 4 in the journal Bioconjugate Chemistry. The authors include lead researcher Judith S. Kempfle, Ph.D., a 2011 and 2012 Emerging Research Grants scientist, as well as Hearing Restoration Project member Albert Edge, Ph.D., both at Harvard Medical School and The Eaton-Peabody Laboratories in Boston.

There are caveats. The research was conducted on animal tissues in a petri dish. It has not yet been tested in living animals or humans. Yet the researchers are hopeful given the similarities of cells and mechanisms involved. McKenna says since the technique works in the laboratory, the findings provide “strong preliminary evidence” it could work in living creatures. They are already planning the next phase involving animals and hearing loss.

The study breaks new ground because researchers developed a novel drug-delivery method. Specifically, it targets the cochlea, a snail-like structure in the inner ear where sensitive cells convey sound to the brain. Hearing loss occurs due to aging or exposure to noise at unsafe levels. Over time, hair-like sensory cells and bundles of neurons that transmit their vibrations break down, as do ribbon-like synapses, which connect the cells.

The researchers designed a molecule combining 7,8-dihydroxyflavone, which mimics a protein critical for development and function of the nervous system, and bisphosphonate, a type of drug that sticks to bones. This pairing delivered the breakthrough solution, the researchers say, as neurons responded to the molecule and regenerated synapses in mouse ear tissue. This led to the repair of the hair cells and neurons, which are essential to hearing.

“We’re not saying it’s a cure for hearing loss,” McKenna says. “It’s a proof of principle for a new approach that’s extremely promising. It’s an important step that offers a lot of hope.” Hearing loss affects two thirds of people over 70 years and 17 percent of all adults in the United States, and it is expected to nearly double in 40 years.

This is adapted from "Hearing Loss Study at USC, Harvard Shows Hope for Millions" on the USC News website. The authors of the April 4, 2018, Bioconjugate Chemistry study, “Bisphosphonate-Linked TrkB Agonist: Cochlea-Targeted Delivery of a Neurotrophic Agent as a Strategy for the Treatment of Hearing Loss,” include lead researcher Judith S. Kempfle, as well as Christine Hamadani, Nicholas Koen, Albert S. Edge, and David H. Jung of Harvard Medical School and The Eaton-Peabody Laboratories/Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston. Kempfle is also affiliated with the University of Tübingen Medical Center. Corresponding author Charles E. McKenna, as well as Kim Nguyen and Boris A. Kashemirov, are at USC Dornsife.

The research was supported by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Herbert Silverstein Otology and Neurotology Research Award, an American Otological Society Research Grant, and a grant from the National Institute of Deafness and other Communicative Disorders (R01 DC007174).

Cochlear to Support Hearing Research By Reaching One Million Ears

Today marks the start of Better Hearing & Speech Month (BHSM), a campaign to advance public knowledge of communication disorders. To celebrate, international hearing implant manufacturer Cochlear is launching the #MillionEar Challenge with the goal of informing one million people about the importance of hearing health and research.

Proceeds from the campaign will benefit Hearing Health Foundation (HHF)’s longstanding Emerging Research Grants (ERG) program. Cochlear has pledged to donate to ERG when the #MillionEar Challenge is met.

“Awareness is at the heart of Hearing Health Foundation's efforts to prevent, treat, and cure hearing loss," said Nadine Dehgan, HHF’s Chief Executive Officer. "I am deeply grateful Cochlear is committed to raising awareness of hearing loss, which will inspire more to pursue hearing tests and life-changing treatments."

HHF staff thanks Cochlear in their own #MillionEar Challenge shirts.

Cochlear’s generous gift will allow HHF to continue funding up-and-coming scientists who investigate various hearing and balance conditions. Such funding has historically led to the development of many new treatments including cochlear implants which, today, benefit more than 300,000 people worldwide.

You can support the #MillionEar campaign with the purchase of a t-shirt, available in child and adult sizes. Read the full press from Cochlear release here.

Designing New Antibiotics That Aren't Harmful to Hearing

Anthony Ricci, Ph.D. (1999–2000 ERG), a professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Stanford University, and Alan Cheng, M.D. (2002–03 ERG), a Stanford associate professor of otolaryngology, are developing a new type of aminoglycosides, a widely used, life-saving class of antibiotic that fights a broad range of serious infections and diseases such as cystic fibrosis and tuberculosis, but that also has the side effect of hearing loss in one in five patients. The pair have been collaborating since 2008, leveraging Ricci’s knowledge of mechanotransduction (how sound wave vibrations are converted into electrical signals) and ion channels. Of the 18 potential replacement antibiotics they created, three show the most promise for preserving hearing while remaining effective in killing bacteria and will be tested further. —Y.L.

Tony Ricci, left, and Alan Cheng have built a team to develop a safe replacement for a type of antibiotic that can cause deafness. The researchers use a patch clamp rig in Ricci’s lab to see which forms of the drug can enter Hair cells — cells crucial for hearing. Max Aguilera-Hellweg photography.

Is It Overstimulation?

By Eric Sherman

My younger son Cole has been wearing cochlear implants (CI) since 2005. He was barely a toddler, between 18 and 24 months old, when he rejected them.

The initial response from our audiologist was, “We just mapped your son, just do your best to keep the processor on his head.” Unique to every CI wearer, mapping adjusts the sound input to the electrodes on the array implanted into the cochlea. It is meant to optimize the CI user’s access to sound.

But after several weeks, and our audio-verbal therapist told us there was something wrong and referred us to another pediatric audiologist, Joan Hewitt, Au.D.

Eric Sherman and his son, Cole

We learned that refusing to wear CI processors is generally a symptom of a problem that a child can’t necessarily express. Their behavior becomes the only way to communicate the issue.

“Our brains crave hearing,” Hewitt says. “Children should want to have their CIs on all the time. If a child resists putting the CIs on in the morning, cries or winces when they are put on, or fails to replace the headpiece when it falls off, there is a strong possibility that the CIs are providing too much stimulation. Some children appear shy or withdrawn because the stimulation is so great that interacting is painful. Others respond to overstimulation by being loud and aggressive.”

Hewitt says research discussed at the Cochlear Implant Symposium in Chicago in 2011 (or CI2011, run by the then-newly created American Cochlear Implant Alliance) addressed the issue of overstimulation. A study that was presented, titled "Overstimulation in Children with Cochlear Implants," listed symptoms that indicated children were overstimulated by their cochlear implants: reluctance or refusal to wear the device, overly loud voices, poor articulation, short attention span or agitated behavior, and no improvement in symptoms despite appropriate therapy.

When the researchers reduced the stimulation levels, they found very rapid improvement in voice quality and vocal loudness and gradual improvement in articulation. Finally, they found “surprising effects on the children's behavior”—the parents reported a marked improvement in attention and reduction in agitation.

In “Cochlear Implants—Considerations in Programming for the Pediatric Population,” in AudiologyOnline, Jennifer Mertes, Au.D., CCC-A, and Jill Chinnici, CCC-A, write: “Children are not little adults. They are indeed, unique, and to address their CI needs, they require an experienced clinician. Most children are unable to provide accurate feedback while the audiologist programs their cochlear implant and therefore, the clinician must take many things into account.”

These include:

The audiologists' past experiences with other patients

Updated information regarding the child's progress (from parents, therapists, and teachers

Audiometric test measures

Observations of the child during programming

Objective measurements

If age appropriate, the clinician will train the child to participate in programming

Many of the decisions made during programming appointments come from the clinician's knowledge and experience, rather than the child's behavioral responses. But your child’s reactions should also be taken into account.

If your child continues to refuse to wear their processors after a remapping, take into consideration your audiologist’s experience and mapping approach and seek a second opinion. When we met with Hewitt, she found our child’s map was overstimulating. Once she remapped using a different approach, our son had no problem wearing his CI processor again.

Los Angeles marketing executive Eric Sherman is the founder of Ci Wear, a patented shirt designed to secure and protect cochlear implant processors. April is National Autism Awareness Month. Read about how Sherman and Cole manage Cole’s hearing loss and autism spectrum disorder conditions in “When It’s Not Just Hearing Loss” in the Fall 2016 issue of Hearing Health.

Let’s Make Noise Safer

By Vicky Chan

April 25 is International Noise Awareness Day, an annual, vital reminder to take a stand against noise exposure and to spread awareness about the underestimated threat of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Seemingly harmless rhythms, roars, and blasts heard daily from music, trains, and machinery are, in fact, among the top offenders of NIHL.

Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) progressively occurs after chronic exposure to loud sounds. The frequency and intensity of the sound level, measured in decibels (dB), increases the risk of NIHL. Gradual hearing loss can result from prolonged contact with noise levels of 85 dB or greater, such as heavy city traffic. Noises of 110 dB or more, like construction (110 dB), an ambulance (120dB), or the pop of firecrackers (140-165 dB) can damage one’s hearing in a minute’s time.

NIHL is the only type of hearing loss that is completely preventable, yet billions of individuals endanger themselves daily. Over 1.1 billion young adults ages 12 to 35—an age group that frequently uses headphones to listen to music—are at risk. Already, an estimated 12.5% of young people ages of 6 to 19 have hearing loss as a result of using earbuds or headphones at a high volume. A device playing at maximum volume (105 dB) is dangerous, so exposure to sounds at 100 dB for more than 15 minutes is highly discouraged.

Most major cities around the world have transit systems that put commuters in contact with sounds at 110 dB. BBC News found that London’s transit systems can get as loud as 110 dB, which is louder than a nearby helicopter taking off. The sound levels of some stations exceed the threshold for which occupational hearing protection is legally required. New York City has one of the largest and oldest subway systems in the world where 91% of commuters exceed the recommended levels of noise exposure annually. In a study on Toronto’s subway system, 20% of intermittent bursts of impulse noises were greater than 114 dB.

People who work in certain fields are more vulnerable to NIHL than others. Professional musicians, for instance, are almost four times as likely to develop NIHL than the general public. Military personnel, who are in extremely close proximity to gunfire and blasts, are more likely to return home from combat with hearing loss and/or tinnitus than any other type of injury. And airport ground staff are surrounded by high-frequency aircraft noises at 140 dB. In all of these professions, the hazard of NIHL can be significantly mitigated with hearing protection.

NIHL is permanent. Increased exposure to excess noise destroys the sensory cells in the inner ears (hair cells), which decreases hearing capacity and leads to hearing loss. Once damaged, the sensory cells cannot be restored. To find a solution, Hearing Health Foundation’s (HHF) Hearing Restoration Project (HRP) conducts groundbreaking research on inner ear hair cell regeneration in hopes of discovering a life-changing cure.

Nearly three-quarters of those who are exposed to loud noises rarely or never use hearing protection. It is our dream that someday, NIHL will be reversible as a result of the HRP. Until then, to make noise safer, HHF advises protection by remembering to Block, Walk, and Turn. Block out noises by wearing earplugs or protective earmuffs. Walk away or limit exposure to high-levels of noises. Turn down the volume of electronic devices.

Sound Processing in Early Brain Regions

To better identify and treat these central auditory processing disorders that appear despite normal ear function, 2016 Emerging Research Grants (ERG) scientist Richard A. Felix II, Ph.D., and colleagues have been investigating how the brain processes complex sounds such as speech.