These details gleaned from this regenerative process in the mouse organoid provides insights into how mammalian supporting cells could be reprogrammed into hair cells.

Headlines in Hearing Restoration

By Yishane Lee

The cornerstone of Hearing Health Foundation for six decades has been funding early-career hearing and balance researchers through its Emerging Research Grants (ERG) program. Many ERG scientists have gone on to obtain prestigious National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding to continue their HHF-funded research; since 1958, each dollar awarded to ERG scientists by HHF has been matched by NIH investments of more than $90. Within the scientific community, ERG is a competitive grant awarded to the most promising investigators, and we’re always especially pleased when our ERG alumni who are now also members of or affiliated with our Hearing Restoration Project consortium make headlines in the mainstream news for their scientific breakthroughs.

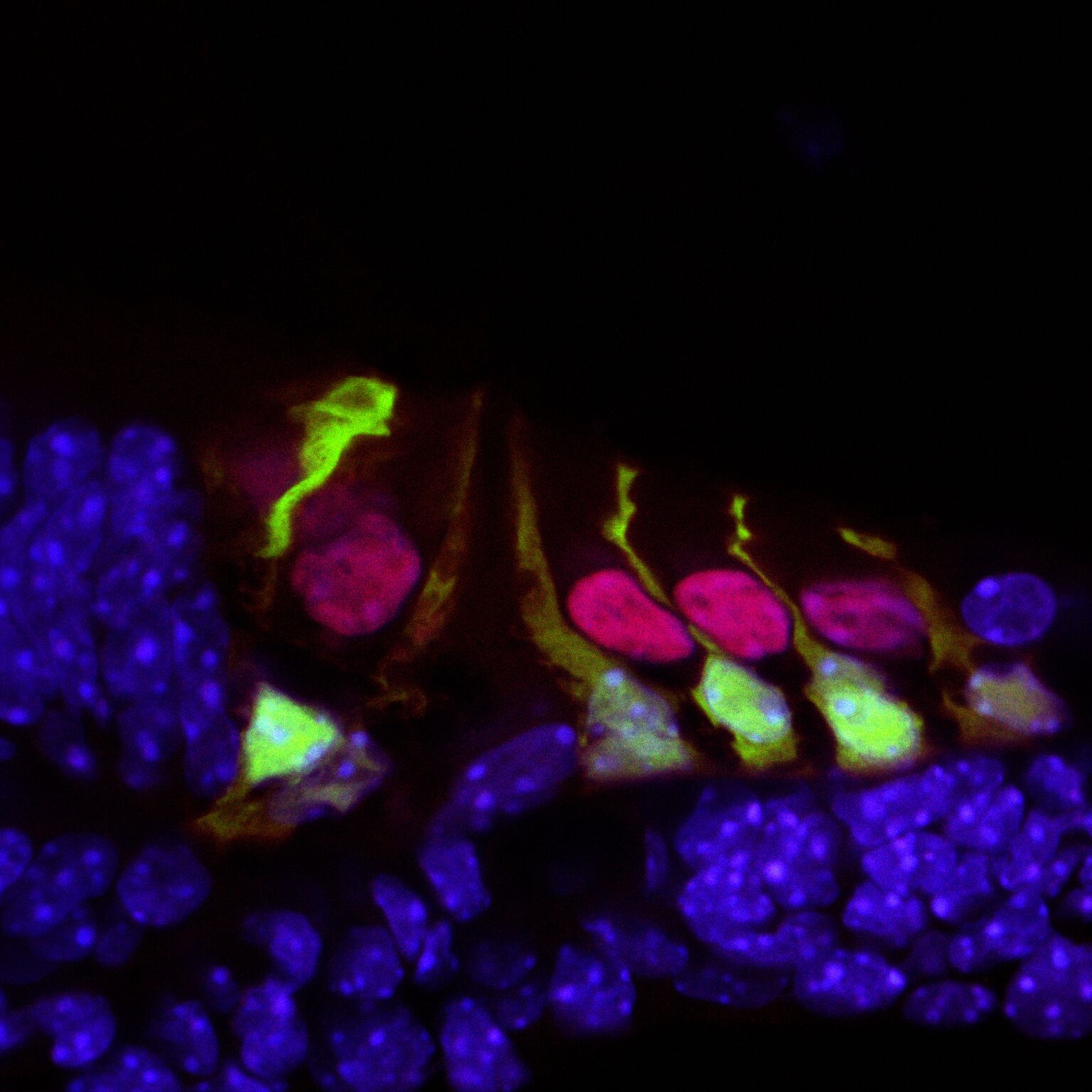

Hair cells in the mouse cochlea courtesy of the lab of Hearing Restoration Project (HRP) member Andy Groves, Ph.D., Baylor College of Medicine.

Ronna Hertzano, M.D., Ph.D. (2009–10): Hearing Restoration Project consortium member Hertzano, an associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and colleagues identified a gene, Ikzf2, that acts as a key regulator for outer hair cells whose loss is a major cause of age-related hearing loss. The Ikzf2 gene encodes helios, a transcription factor (a protein that controls the expression of other genes). The mutation of the gene in mice impairs the activity of helios in the mice, leading to an outer hair cell deficit.

Reporting in the Nov. 21, 2018, issue of Nature, the team tested whether the opposite effect could be created—if an abundance of helios could boost the population of outer hair cells. They introduced a virus engineered to overexpress helios into the inner ear hair cells of newborn mice, and found that some mature inner hair cells became more like outer hair cells by exhibiting electromotility, a property limited to outer hair cells. The finding that helios can drive inner hair cells to adopt critical outer hair cell characteristics holds promise for future treatments of age-related hearing loss.

Patricia White, Ph.D. (2009, 2011), with Hearing Restoration Project member Albert Edge, Ph.D.: White, a research associate professor at the University of Rochester Medical Center, Edge, a professor of otolaryngology at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School, and team have been able to regrow the sensory hair cells found in the mouse cochlea. The study, published in the European Journal of Neuroscience on Sep. 30, 2018, builds on White’s prior research that identified a family of receptors called epidermal growth factor (EGF) that is responsible for activating supporting cells in the auditory organs of birds. When triggered, these cells proliferate and foster the generation of new sensory hair cells. In mice, EGF receptors are expressed but do not drive regeneration of hair cells, so it could be that as mammals evolved, the signaling pathway was altered.

The new study aimed to unblock the regeneration of hair cells and also integrate them with nerve cells, so they are functional, by switching the EGF signaling pathway to act as it does in birds. The team focused on a specific receptor called ERBB2, found in supporting cells. They used a number of methods to activate the EGF signaling pathway: a virus targeting ERBB2 receptors; mice genetically altered to overexpress activated ERBB2; and two drugs developed to stimulate stem cell activity in the eye and pancreas that are already known to activate ERBB2 signaling. The researchers found that activating the ERBB2 pathway triggered a cascading series of cellular events: Supporting cells began to proliferate and started the process of activating other neighboring stem cells to lead to “apparent supernumerary hair cell formation,” and these hair cells’ integration with the network of neurons was also supported.

This was prepared using press materials from the University of Maryland and the University of Rochester. For more, see hhf.org/hrp.

The People Behind the Science

By Yishane Lee

Eight years ago we introduced a column called “Meet the Researcher.” Placed on the last page of the magazine (prime editorial real estate!), the MTR column was designed as a way to give our Emerging Research Grants (ERG) scientists a place to talk about their ERG project in more detail—and in lay terms for our readers—including its genesis, planned execution, and future goals.

Credit: Jane G. Photography

“Meet the Researcher” also is an opportunity for us to glimpse the person behind the science, with the researchers sharing how they became interested in their field and whether they have any personal connection to hearing conditions. Perhaps not surprisingly, many researchers do become interested in hearing and balance science as a result of their own experience with hearing loss. For instance, 2010 ERG scientist Judith Kempfle, M.D., told us she received an artificial eardrum at age 13, after many ear infections that her brother also got when they were kids growing up in Germany. With her ERG funded by the Royal Arch Masons General Grand Chapter International, Kempfle has gone on to work on many papers with Hearing Restoration Project member Albert Edge, Ph.D. (including a recent one about the effort to deliver drugs directly to the inner ear).

Ed Bartlett, Ph.D., Purdue University

Also a Royal Arch Masons grantee, 2011 ERG scientist Ed Bartlett, Ph.D., who published research on the lasting effects of blast shock waves on auditory processing, remembers asking his teacher whether we actually hear thoughts or if it something else. “So, I guess I was destined for auditory neuroscience,” says Bartlett, who also earned ERG funding in 2003, 2004, and 2009.

2011 and 2012 ERG scientist Regie Santos-Cortez, M.D., Ph.D., who earned the Collette Ramsey Baker Award named after HHF’s founder, spoke about the challenges of getting access to genetic information for her study that eventually pinpointed a gene mutation linked to a predisposition for ear infections. 2012 ERG scientist Bradley J. Walters, Ph.D., says he started out studying evolutionary biology, switched to studying regenerating damaged brain tissue, and then switched to hearing research. “I realized a lot of the ideas I had been working on in the brain could be applied to the ear,” he says. A 2017 paper he coauthored described successfully using gene therapy to regenerate hair cells in adult mice.

Alan Kan, Ph.D., University of Wisconsin, Madison

An early love of logic puzzles for 2013 ERG scientist Alan Kan, Ph.D., a Royal Arch Masons grantee, turned into studying audio engineering and his 2018 paper looking at how to improve speech understanding among people who use bilateral cochlear implants. Fellow 2013 Royal Arch Masons recipient Ross Maddox, Ph.D., remembers varying how he cupped his hands over his ears to get different sounds, leading to an interest in auditory processes and, eventually, research on how auditory and visual input is synthesized to understand sound.

After 26 years as a clinical audiologist, Royal Arch Masons 2014 ERG scientist Samira Anderson, Ph.D., switched to research. “Part of my motivation came from working with patients who struggled with their hearing aids,” she says. “I was frustrated that I was unable to predict who would benefit from hearing aids based on the results of audiological evaluations.” She produced three papers on the topic, bringing us closer to improving fit for and increasing the use of hearing aids.

Likewise, fellow Royal Arch Masons grantee Srikanta Mishra, Ph.D., produced two papers, one in 2017 and one in 2018, on children’s hearing that stemmed from his 2014 ERG grant—work that also led to a prestigious National Institutes on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders grant. And we liked the backstory for 2014 ERG scientist Brad Buran, Ph.D., so much that we put him on the cover of our magazine. Buran, who wears cochlear implants, multitasks during happy hour with his colleagues. “In an environment where it’s hard to hear,” he says, “within an hour they have all the information they need to use Cued Speech,” which uses visual representations of phonemes.

Beula Magimairaj, Ph.D., University of Central Arkansas

In 2015, we expanded our coverage of ERG recipients, so that every grantee is profiled in a “Meet the Researcher” column, all available online. Three papers resulted from the Royal Arch Masons grant received by 2015 ERG scientist Beula Magimairaj, Ph.D., and her research into children’s speech perception in noise and auditory processing (the third paper is in press). Funded by Hyperacusis Research Ltd., 2015 ERG scientist Kelly Radziwon, Ph.D., has managed to create a reliable animal model for loudness hyperacusis (essentially, inducing loudness intolerance in a rat and making sure it reacts to gradually increasing sound intensities) as well as finding a potential link between neuroinflammation and hyperacusis. 2015 and 2016 ERG scientist Wafaa Kaf, Ph.D.—who has 18 other family members (and counting!) who work in science—has been investigating Ménière’s disease, publishing on improving its diagnosis as it can be mistaken for other conditions, and the use of electrocochleography (ECochG) for diagnosing and monitoring the hearing and balance disorder.

Elizabeth McCullagh, Ph.D., University of Colorado

A karaoke fan who admits he “cannot resist Celine Dion,” Royal Arch Masons 2016 ERG scientist Richard Felix II, Ph.D. published on the greater-than-expected role of lower-level brain regions on speech processing. Fellow Royal Arch Masons grantee, 2016 ERG scientist Elizabeth McCullagh, Ph.D., makes her own cheese and beer in between uncovering new clues to sound localization problems in the genetic condition known as Fragile X syndrome, which can lead to autism.

Rahul Mittal, Ph.D., University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

2016 ERG scientist Harrison Lin, Ph.D., funded by The Barbara Epstein Foundation Inc., credits his older brother, also an otolaryngologist, for developing in him a love for science. He coauthored a January 2018 JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery paper that detailed the gap between hearing loss diagnoses and treatments. 2016 ERG scientist Rahul Mital, Ph.D., who says he’d write fiction if not doing research, published an overview of hair cell regeneration, and Julia Campbell, Au.D., Ph.D., whose 2016 grant was funded by the Les Paul Foundation, understands firsthand what is feels like to have tinnitus, a topic she recently published a paper that investigated mild tinnitus in young patients with typical hearing. Hyperacusis Research-funded 2016 ERG scientist Xiying Guan, Ph.D., whose parents grew up doing manual labor in China, published a paper evaluating a treatment for conductive hyperacusis.

Some of our 2017 ERG scientists are already publishing. Royal Arch Masons grantee Inyong Choi, Ph.D., produced research on hybrid cochlear implants, which make use of residual hearing to produce more natural hearing. Oscar Diaz-Horta, Ph.D., whose 2017 ERG grant was funded by the Children’s Hearing Institute, investigated hair cell bundle structure and orientation. Very regretfully, Diaz-Horta died unexpectedly just as this paper was published.

Ian Swinburne, Ph.D., Harvard Medical School

Ian Swinburne, Ph.D., one of our Ménière’s Disease Grants scientists during its inaugural year in 2017, published a paper detailing one possible cause of Ménière’s disease. Swinburne and team discovered a structure in the inner ear’s endolymphatic sac acts a pressure-sensitive relief valve. Its failure may account for problems with inner ear fluid pressure and volume that may lead to hearing and balance disorders, including Ménière’s. “One activity I loved as a child was waterworks: building canals and aqueducts out of sand or dirt and then pouring water through them just to watch it flow,” he says. “Now I recognize an echo of that play in my study of water pressure and flow within the ear.”

We very much look forward to published research from all of our ERG scientists, including our latest crop of 2018 ERG scientists, whose ranks include a former college mascot, a violinist, a horse rider (of a horse named Gandalf), a Tibetan neuroscientist (and cookbook writer), a cricket player, a nonprofit cook who has prepared meals for 50,000 people, a dancer (including in flash mobs), and a builder of airplane scale models. Our ERG scientists deliver surprises of all sorts, from their backgrounds and how they got to where they are to the ground-breaking science they are spearheading in the lab.

We need your help supporting innovative hearing and balance science through our Emerging Research Grants program. Please make a contribution today.

Study Points to Possible New Therapy for Hearing Loss

University of Rochester Medical Center research associate professor Patricia White, Ph.D. (2009 and 2011 ERG), with Hearing Restoration Project member and Harvard Medical School professor Albert Edge, Ph.D., and team have been able to regrow the sensory hair cells found in the mouse cochlea. The study, published in the European Journal of Neuroscience on Sep. 30, 2018, builds on White’s prior research that identified a family of receptors called epidermal growth factor (EGF) that is responsible for activating supporting cells in the auditory organs of birds. When triggered, these cells proliferate and foster the generation of new sensory hair cells. In mice, EGF receptors are expressed but do not drive regeneration of hair cells, so it could be that as mammals evolved, the signaling pathway was altered.

The new study aimed to unblock the regeneration of hair cells and also integrate them with nerve cells, so they are functional, by switching the EGF signaling pathway to act as it does in birds. The team focused on a specific receptor called ERBB2, found in supporting cells. They used a number of methods to activate the EGF signaling pathway: a virus targeting ERBB2 receptors; mice genetically altered to overexpress activated ERBB2; and two drugs developed to stimulate stem cell activity in the eye and pancreas that are already known to activate ERBB2 signaling. The researchers found that activating the ERBB2 pathway triggered a cascading series of cellular events: Supporting cells began to proliferate and started the process of activating other neighboring stem cells to lead to “apparent supernumerary hair cell formation,” and these hair cells’ integration with the network of neurons was also supported. —University of Rochester

Novel Drug-Delivery Method to the Inner Ear

By Gary Polakovic, USC News

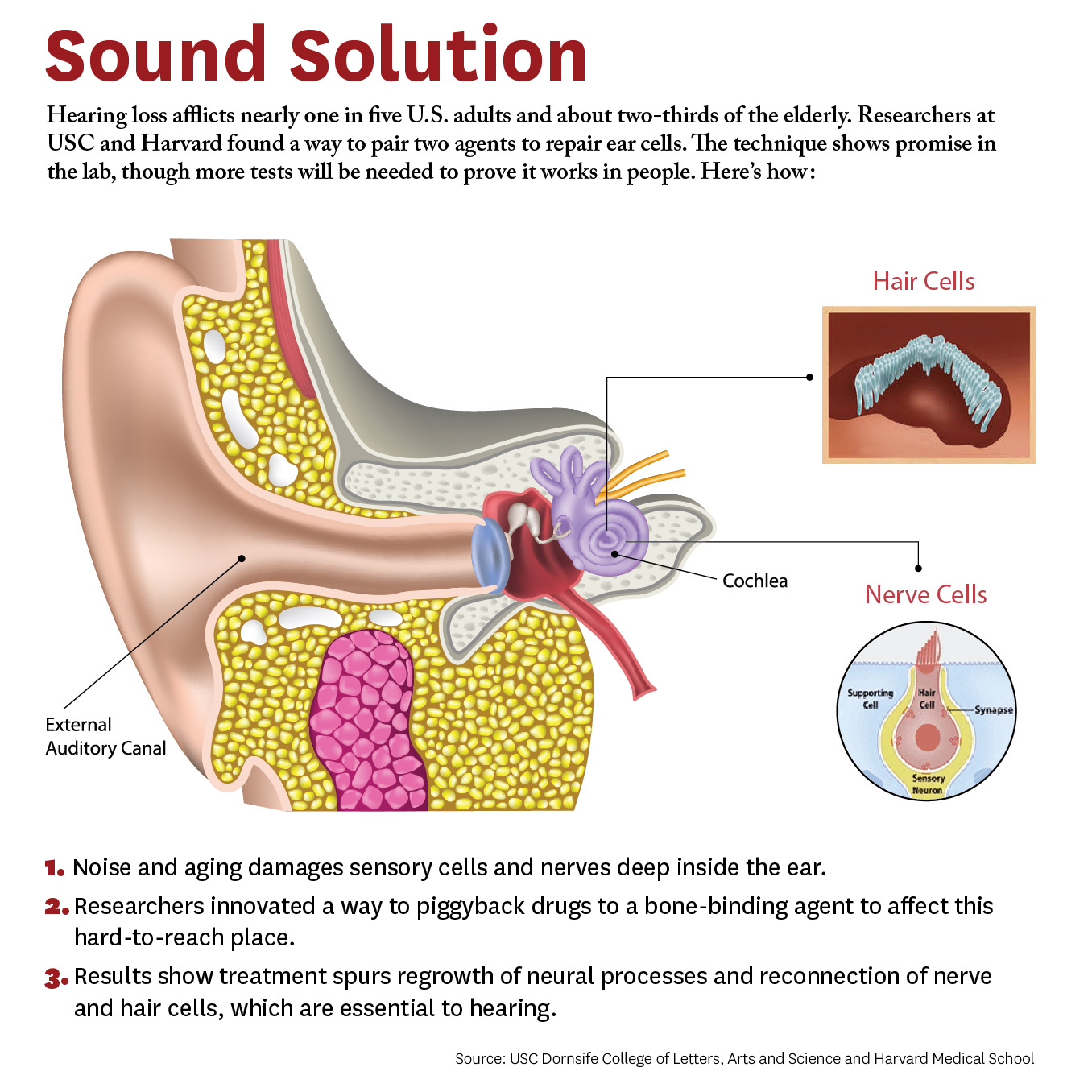

Researchers have developed a new approach to be able to repair cells deep inside the ear. The study, conducted by scientists at University of Southern California (USC) and Harvard University, demonstrates a novel way for a future drug to zero in on damaged nerves and cells inside the ear.

Credit: Matthew Pla Savino/USC News

“What’s new here is we figured out how to deliver a drug into the inner ear so it actually stays put and does what it’s supposed to do, and that’s novel,” says Charles E. McKenna, Ph.D., a corresponding author for the study and chemistry professor at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences.

“Inside this part of the ear, there’s fluid constantly flowing that would sweep dissolved drugs away, but our new approach addresses that problem. This is a first for hearing loss and the ear,” McKenna adds. “It’s also important because it may be adaptable for other drugs that need to be applied within the inner ear.”

The paper was published April 4 in the journal Bioconjugate Chemistry. The authors include lead researcher Judith S. Kempfle, Ph.D., a 2011 and 2012 Emerging Research Grants scientist, as well as Hearing Restoration Project member Albert Edge, Ph.D., both at Harvard Medical School and The Eaton-Peabody Laboratories in Boston.

There are caveats. The research was conducted on animal tissues in a petri dish. It has not yet been tested in living animals or humans. Yet the researchers are hopeful given the similarities of cells and mechanisms involved. McKenna says since the technique works in the laboratory, the findings provide “strong preliminary evidence” it could work in living creatures. They are already planning the next phase involving animals and hearing loss.

The study breaks new ground because researchers developed a novel drug-delivery method. Specifically, it targets the cochlea, a snail-like structure in the inner ear where sensitive cells convey sound to the brain. Hearing loss occurs due to aging or exposure to noise at unsafe levels. Over time, hair-like sensory cells and bundles of neurons that transmit their vibrations break down, as do ribbon-like synapses, which connect the cells.

The researchers designed a molecule combining 7,8-dihydroxyflavone, which mimics a protein critical for development and function of the nervous system, and bisphosphonate, a type of drug that sticks to bones. This pairing delivered the breakthrough solution, the researchers say, as neurons responded to the molecule and regenerated synapses in mouse ear tissue. This led to the repair of the hair cells and neurons, which are essential to hearing.

“We’re not saying it’s a cure for hearing loss,” McKenna says. “It’s a proof of principle for a new approach that’s extremely promising. It’s an important step that offers a lot of hope.” Hearing loss affects two thirds of people over 70 years and 17 percent of all adults in the United States, and it is expected to nearly double in 40 years.

This is adapted from "Hearing Loss Study at USC, Harvard Shows Hope for Millions" on the USC News website. The authors of the April 4, 2018, Bioconjugate Chemistry study, “Bisphosphonate-Linked TrkB Agonist: Cochlea-Targeted Delivery of a Neurotrophic Agent as a Strategy for the Treatment of Hearing Loss,” include lead researcher Judith S. Kempfle, as well as Christine Hamadani, Nicholas Koen, Albert S. Edge, and David H. Jung of Harvard Medical School and The Eaton-Peabody Laboratories/Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston. Kempfle is also affiliated with the University of Tübingen Medical Center. Corresponding author Charles E. McKenna, as well as Kim Nguyen and Boris A. Kashemirov, are at USC Dornsife.

The research was supported by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Herbert Silverstein Otology and Neurotology Research Award, an American Otological Society Research Grant, and a grant from the National Institute of Deafness and other Communicative Disorders (R01 DC007174).