As in its draft recommendation released a few months earlier (which I wrote about), the USPSTF “concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for hearing in older adults.”

The Challenge of Hearing Well in Background Noise

What is important to know is that hearing—and understanding— speech in the presence of background noise is a complex physiological process. Wearing a hearing aid can usually improve the way sounds are presented to the ear, but it cannot change the way your brain processes the signal your ear receives.

Advancing Accessibility in the Audiology Profession

By Lauren McGrath

Born with a profound sensorineural hearing loss, Jessica Hoffman, Au.D., CCC-A, never believed she could become an audiologist. In fact, she didn’t consider the profession until her final year as a biopsychology undergraduate at Tufts University.

By then, Dr. Hoffman was the recipient of successful hearing loss intervention and treatment for two decades. Diagnosed at 13 months, she was fitted with hearing aids by age two, practiced speech and hearing at the New York League for the Hard of Hearing (today the Center for Hearing and Communication) until five, and learned American Sign Language (ASL) at 10. She pursued a mainstream education since preschool with daily visits from a teacher of the deaf. Dr. Hoffman received cochlear implants at ages 14 and 24, respectively and, in college and graduate school, enjoyed a variety of classroom accommodations including ASL interpreters, CART, C-Print, notetakers, and FM systems.

After Tufts, Dr. Hoffman worked as a lab technician at Massachusetts Eye and Ear as her interests in studying hearing began to grow. But she doubted her abilities to perform key tasks in audiology, like speech perception tests and listening checks with patients. After speaking with others in the field with hearing loss, she became less apprehensive. Engaging with mentors like Samuel Atcherson, Ph.D., and Suzanne Yoder, Au.D., who have greatly advanced opportunities for individuals with hearing loss in audiology, further cemented Dr. Hoffman’s self-confidence. In 2010, she completed her Doctor of Audiology from Northwestern University.

Today, Dr. Hoffman is happy to work with both children and adults at the ENT Faculty Practice/Westchester Cochlear Implant Program in Hawthorne, NY. She takes pride in helping her patients realize that they are not alone with hearing loss and that technology, like her own cochlear implants, can provide immense benefits to communication. Dr. Hoffman is motivated to help her patients understand that hearing loss does not define who one is and can be viewed as a gain rather than as a limitation.

Dr. Hoffman’s career is not exempt from challenges. Fortunate to receive accommodations as a child and young adult, she is disappointed by the tools that are missing in a field that serves those with hearing loss. Though she credits her own workplace as being very understanding, Dr. Hoffman points out the difficulties she experiences during team meetings and conversations with patients who speak English as a second language. She is grateful to have considerate colleagues who will repeat themselves as needed or offer to facilitate verbal communication with non-native English-speaking patients.

At audiology conferences, however, necessities like CART, FM systems, and/or interpreters are often lacking for professionals with hearing loss. Dr. Hoffman and others with hearing loss in the audiology field have petitioned to encourage accessibility at such events. She has had to take on the responsibility of finding CART vendors for conference organizers to ensure her own optimal listening experience. She reports being brushed off by meeting leaders and a sense of doubt in her abilities and those of her colleagues with hearing loss.

Dr. Hoffman also wishes to see greater accessibility in audiology offices nationwide, including recorded speech perception materials, captioning for videos or TV shows in the waiting room, and email exchanges with patients, rather than phone calls. She’d like all audiology staff to be well-versed in communicating with people with hearing loss and to have a strong understanding of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) as it pertains to hearing loss. Dr. Hoffman also thinks facilities would benefit from hiring ASL interpreters or Cued Speech transliterators as needed. Her ideas would help professionals like her and patients alike.

Accommodations for people with hearing loss and other disabilities in academics, public sectors, and the workforce—audiology included—should be provided without question, says Dr. Hoffman, who has had the burden of reversing many people’s misconceptions about her capability to thrive independently in her career. “The self-advocacy never ends, but it has made me stronger and more confident in my own abilities as a deaf person. I am proud to have a hearing loss because it has shaped me into the person I am today.”

Receive updates on life-changing hearing research and resources by subscribing to HHF's free quarterly magazine and e-newsletter.

Is It Overstimulation?

By Eric Sherman

My younger son Cole has been wearing cochlear implants (CI) since 2005. He was barely a toddler, between 18 and 24 months old, when he rejected them.

The initial response from our audiologist was, “We just mapped your son, just do your best to keep the processor on his head.” Unique to every CI wearer, mapping adjusts the sound input to the electrodes on the array implanted into the cochlea. It is meant to optimize the CI user’s access to sound.

But after several weeks, and our audio-verbal therapist told us there was something wrong and referred us to another pediatric audiologist, Joan Hewitt, Au.D.

Eric Sherman and his son, Cole

We learned that refusing to wear CI processors is generally a symptom of a problem that a child can’t necessarily express. Their behavior becomes the only way to communicate the issue.

“Our brains crave hearing,” Hewitt says. “Children should want to have their CIs on all the time. If a child resists putting the CIs on in the morning, cries or winces when they are put on, or fails to replace the headpiece when it falls off, there is a strong possibility that the CIs are providing too much stimulation. Some children appear shy or withdrawn because the stimulation is so great that interacting is painful. Others respond to overstimulation by being loud and aggressive.”

Hewitt says research discussed at the Cochlear Implant Symposium in Chicago in 2011 (or CI2011, run by the then-newly created American Cochlear Implant Alliance) addressed the issue of overstimulation. A study that was presented, titled "Overstimulation in Children with Cochlear Implants," listed symptoms that indicated children were overstimulated by their cochlear implants: reluctance or refusal to wear the device, overly loud voices, poor articulation, short attention span or agitated behavior, and no improvement in symptoms despite appropriate therapy.

When the researchers reduced the stimulation levels, they found very rapid improvement in voice quality and vocal loudness and gradual improvement in articulation. Finally, they found “surprising effects on the children's behavior”—the parents reported a marked improvement in attention and reduction in agitation.

In “Cochlear Implants—Considerations in Programming for the Pediatric Population,” in AudiologyOnline, Jennifer Mertes, Au.D., CCC-A, and Jill Chinnici, CCC-A, write: “Children are not little adults. They are indeed, unique, and to address their CI needs, they require an experienced clinician. Most children are unable to provide accurate feedback while the audiologist programs their cochlear implant and therefore, the clinician must take many things into account.”

These include:

The audiologists' past experiences with other patients

Updated information regarding the child's progress (from parents, therapists, and teachers

Audiometric test measures

Observations of the child during programming

Objective measurements

If age appropriate, the clinician will train the child to participate in programming

Many of the decisions made during programming appointments come from the clinician's knowledge and experience, rather than the child's behavioral responses. But your child’s reactions should also be taken into account.

If your child continues to refuse to wear their processors after a remapping, take into consideration your audiologist’s experience and mapping approach and seek a second opinion. When we met with Hewitt, she found our child’s map was overstimulating. Once she remapped using a different approach, our son had no problem wearing his CI processor again.

Los Angeles marketing executive Eric Sherman is the founder of Ci Wear, a patented shirt designed to secure and protect cochlear implant processors. April is National Autism Awareness Month. Read about how Sherman and Cole manage Cole’s hearing loss and autism spectrum disorder conditions in “When It’s Not Just Hearing Loss” in the Fall 2016 issue of Hearing Health.

The Hearing Journey: What Matters to You?

By Laura Friedman

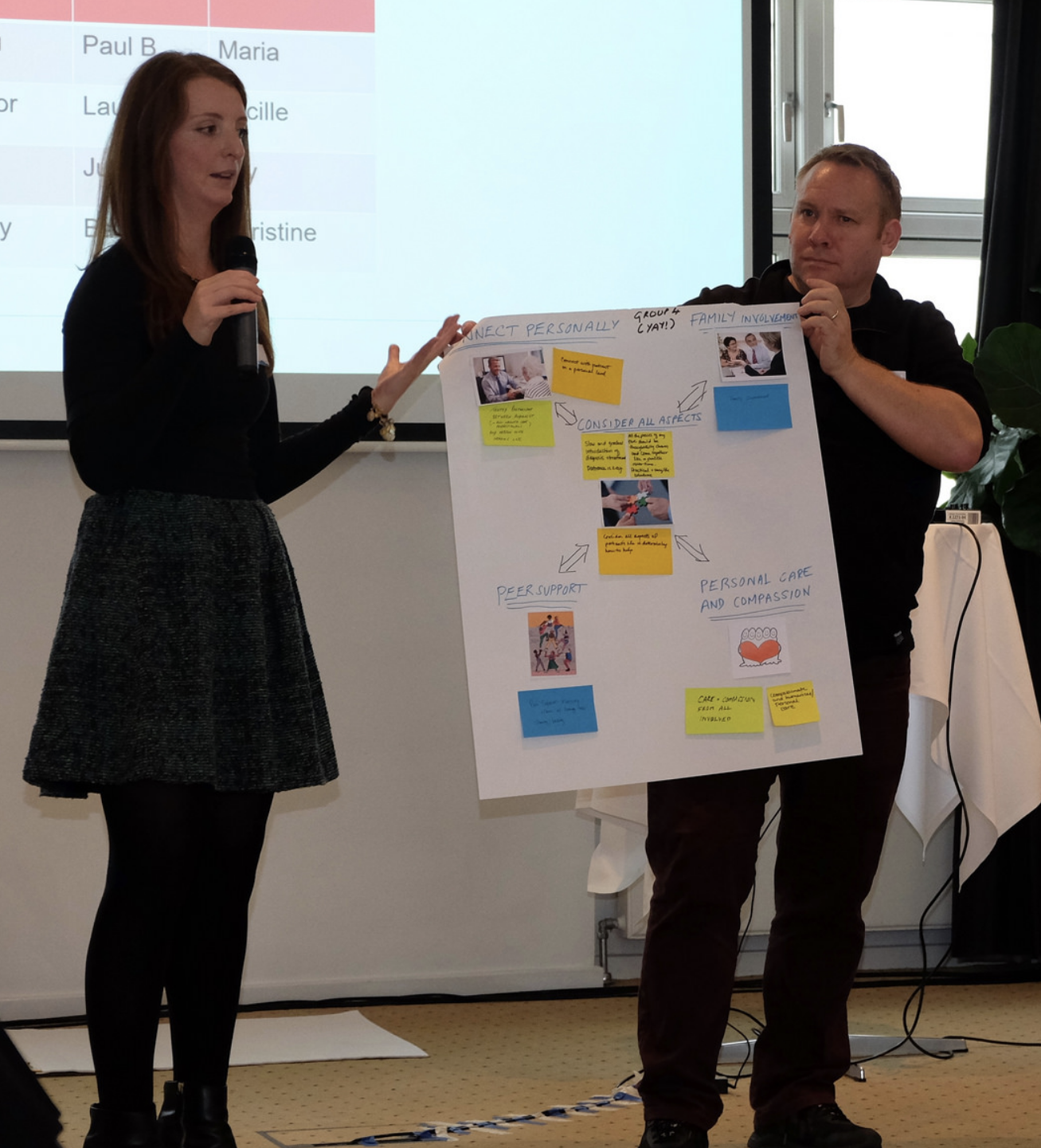

Participants used post-it notes to express their desired improvements to the hearing journey. Photo by Darcy Benson.

Recently, in October 2017, I represented Hearing Health Foundation (HHF) at a seminar that took place in Skodsborg, Denmark, where I and 30 other attendees from around the world were tasked with closely exploring and developing tactical strategies to better the patient experience when receiving audiological care.

The seminar conversations focused on person-centered care, a treatment model that focuses on the whole person, rather than just the ailment or condition experienced by the patient. The peer-reviewed Permanente Journal says that person-centered care is “based on accumulated knowledge of people, which provides the basis for better recognition of health problems and needs over time and facilitates appropriate care for these needs in the context of other needs.” Furthering this sentiment, the World Health Organization identifies empowerment, participation, the central role of the family, and an end to discrimination as the core values of person-centered care.

The two-day symposium was titled, “The Hearing Journey: What Matters to You?” The 31 attendees fell into one or more of the following groups: individuals with hearing loss, representatives from prominent consumer-driven associations for people with hearing loss, audiologists, and hearing healthcare thought leaders. The conference was hosted by the Ida Institute, a Denmark-based nonprofit that aims to better understand human dynamics associated with hearing loss.

The symposium participants pose as a group. Photo by Darcy Benson.

One of the most eye-opening takeaways was recognizing that all those who are part of the care-cycle feel shared sentiments of frustration, poor communication, lack of access, and high costs. Addressing each of these hurdles from a variety of vantage points is key to bettering person-centered care and may not be limited to just audiological care, but rather medical care as whole.

Exercises and projects resulted in several meaningful insights related to person-focused hearing healthcare. We spoke openly about stigma, barriers to rehabilitation, and the need for creating a “new narrative” for how we speak about hearing loss. Changing how we talk about hearing loss, such as how our current nomenclature addresses it as a loss or deficit, will hopefully play a role in changing social stigmas and taboos experienced by those who are hard of hearing, like myself.

HHF's Laura Friedman presents to the group with Paul Breckell, Chief Executive of Action on Hearing Loss. Photo by Darcy Benson.

All parties stressed the importance of including caregivers and family members in the rehabilitation process, and the need for a multidimensional model of care to address the psychological and emotional aspects of hearing care. This included developing a “human audiogram” to discuss diagnoses and their subsequent treatment options in more friendly terms that empowers the patient, rather than discouraging them. It was also advised that clinicians should be more cognizant that diagnoses are difficult for the patient to come to terms with and remember that the most successful patients want treatment, but that it may take time for them to feel motivated to take that next step. Follow-up appointments, rather than immediate discussion of treatment options, was a suggestion most agreed would serve the patient and clinician well.

I feel honored to had been afforded the opportunity to represent HHF at this important symposium and to meet and learn from fellow leaders in the hearing healthcare space. I look forward to working with Ida and my fellow attendees to develop and employ tangible tools and solutions to better a patient’s hearing journey both in and out the audiologist's office, as well as provided better resources to health care providers.

Laura Friedman is the Communications and Programs Manager of Hearing Health Foundation. Read her hearing loss story in the Spring 2016 issue of Hearing Health magazine.

AudiologyNow! 2017

By Kathleen Wallace

The American Academy of Audiology’s (AAA) annual conference, AudiologyNow!, took place in the Indianapolis Convention Center in early April. Although four days of lectures addressed nearly every aspect of the audiological scope of practice, one overarching theme emerged this year: How will the field of audiology evolve from here?

This past year has posed various disruptions to the field of audiology, such as how over-the-counter hearing aid legislation will change delivery of services, how the continued interest in personal sound amplification products (PSAPs, also called “hearables”) will guide consumer choice, and how to improve evaluations and interventions to best serve individuals with hearing loss. These questions, along with many others, fueled an exciting dialogue among professionals from around the country.

AAA President Ian Windmill, Ph.D., urged members of the academy to embrace disruptions to the field, including the recently introduced legislation for nonprescription hearing aids. Although these changes may appear as an encroachment on the audiological scope of practice, Dr. Windmill urged that these may actually be beneficial to the field.

Dr. Windmill said hearing healthcare has never been more in the public eye or as highly discussed by health officials, politicians, and consumers than in this past year. This increased awareness could lead to the prioritization of hearing health, as consumers grow more cognizant of the repercussions of hearing loss. Furthermore, the introduction of hearing solutions at various price points and technology levels may improve accessibility. If audiologists were to embrace these alternatives to intervention, they will successfully evolve with the field while simultaneously demonstrating to consumers their dedication to patient-centered care.

This sentiment was echoed throughout the conference’s sessions. Additionally, multiple lectures discussed how audiologists could improve delivery of patient-centered care by improving counseling skills, utilization of self-assessments, and consumer education to shift the locus of control from care provider to joint decision-making between the consumer and the hearing provider.

Lastly, leading professionals in the field encouraged a return to the audiologists’ roots as rehabilitative professionals. In the years since the audiological scope of practice expanded to include the ability to dispense hearing aids, audiologists have slowly shifted their focus from providing rehabilitative services to a device-driven service centered on hearing aids. However, the delivery of unprecedented auditory rehabilitation to foster successful communication strategies will enable our profession to succeed in the face of the many disruptions to hearing technology.

AAA’s willingness to acknowledge the challenges facing hearing healthcare is very promising to its successful evolution as a field. Although the field of audiology is currently experiencing some growing pains, many hearing healthcare professionals are embracing this opportunity to rethink the delivery of care and how to improve patient satisfaction by challenging the status quo.

Audiology Awareness Month

By Morgan Leppla

October is Audiology Awareness Month and Hearing Health Foundation would like to thank audiologists for all they do in diagnosing, managing, and treating hearing loss and other hearing disorders.

Pioneering ear, nose, and throat physiologist, Hallowell Davis may have coined the word audiologist in the 1940s when he decided that the then-common term “auricular training” sounded like a way to teach people how to wiggle their ears. Fortunately, their role in promoting health is far more important than that.

Audiologists diagnose and treat hearing loss, tinnitus, and balance disorders. Some of their main responsibilities include:

Prescribing and fitting hearing aids

Being members of cochlear implant teams

Designing and implementing hearing preservation programs

Providing hearing rehabilitation services

Screening newborns for hearing loss

They also work in a variety of settings that include private practices, hospitals, schools, universities, and for the government, like in VA hospitals (run by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). Audiologists must be licensed or registered to practice in all states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Becoming an audiologist requires post-secondary education. One could earn a doctor of audiology (Au.D.), a master’s degree (M.A. or M.S.), or if interested in pursuing a research doctorate, a Ph.D.

The American Academy of Audiology provides a code of ethics that ought to structure audiologists’ professional behavior. As in other medical professions, audiologists should strive to act in patients’ best interests and deliver the highest quality care they can while not discriminating against or exploiting whom they serve.

Audiologists are principal agents in hearing health. Their contributions to preserving hearing and preventing hearing and balance diseases are crucial to the well-being of millions.

Learn more about hearing healthcare options at “Looking for Hearing Aids? Find the Right Professional First.”

I Lost My Hearing in My Forties. Here's How I Handled It.

By Mary Louise Kelly

The interesting thing about going deaf is you don’t realize it’s happening. It’s impossible to pinpoint when everyone began to mumble, when you ceased hearing your own footsteps clicking down a hall.

“Is it the accents?” my husband asked when I complained that the actors on Downton Abbey spoke too fast. We started watching with subtitles. At the theater, I focused on the beauty of the sets and costumes because—though I would have denied this—I couldn’t follow the dialogue. Meanwhile, car horns and sirens dimmed. Packages didn’t arrive, yet the UPS man insisted he’d rung the bell three times. “Impossible,” I shot back. “I was home.”

My lowest moment came last spring at a reading to promote my first novel. A woman rose and recounted what I later learned was a risqué tale about a CIA spy (the book was an espionage thriller), then asked a question that had the audience in stitches. I squirmed, laughed along, and responded with what was surely a non sequitur, as I’d caught barely a word of what she’d said. In the taxi home, I thought: Enough.

Still, none of this prepared me for sitting in an audiologist’s office at age 43, being told that I suffered severe hearing loss. How severe? In one test, he stood across the room, spoke a series of words in a normal voice, and asked me to repeat them.

“Void,” he said.

“Void,” I repeated.

“Ditch,” he said.

“Ditch.”

Out of 20, I got 16. “Not perfect,” I sniffed, “but hardly severe.”

He repeated the test, now holding a sheet of paper before his face.

“Mumble,” he said.

“Um . . . repeat that one?”

“Mumble mumble.”

“Shoelace?”

“Nope. Mumbledy mumble.”

This time, I got 6 out of 20. When I couldn’t see his lips move, I missed 70 percent of what he said.

“How are you even functioning?” he inquired, genuinely mystified.

As a reporter, I’ve spent time on aircraft carriers, in helicopters, in war zones. For two decades, I’ve edited stories on deadline through headphones cranked too loud. But the most likely explanation for my hearing loss? Genetics. My father is hard of hearing. So are his sisters and 96-year-old mother. I’ve long known what loomed in my future—I just hadn’t expected it so early.

My first day with hearing aids, I went about my routine with a sense of wonder. It was astonishing to rediscover that pop songs had words I could sing along to. “Have been bopping to an ’80s dance mix all morning,” I posted on Facebook. “I challenge anyone to deny Debbie Gibson was a genius ahead of her time.” (To which came the inevitable reply: “You need to get your hearing checked.”)

By day two, I was on sensory overload. Starbucks left me near tears—I’d had no idea frothing milk made such a racket. I jogged in Rock Creek Park and for the first time in years didn’t jump every time cyclists whizzed past, because I could hear them coming.

The doctors can’t say whether my hearing has stabilized or will worsen. And hearing aids are an imperfect solution. The experience is different from, say, getting glasses and instantly being able to see. It takes time for the brain to adjust, to relearn the pathways it once knew. You almost never recover all that has been lost.

But you do learn to savor small triumphs. The other day, the UPS driver rang my doorbell and I heard him—and tipped big. I still can’t watch TV without subtitles. But at a play recently, the curtain rose and I slumped in sheer relief at being able to follow the words. Not every line, but enough. I’m holding onto that theater program, a memento of a pleasure once dimmed, now mine once more.

Mary Louise Kelly is a contributing editor at The Atlantic. She has spent two decades reporting on national security and international affairs for NPR and the BBC. As NPR’s intelligence and defense correspondent, she covered wars, terrorism, and rising nuclear powers. Kelly has also anchored NPR programs including “Morning Edition” and “All Things Considered.” She has taught national security and journalism at Georgetown University. Kelly’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Newsweek, Politico, and others. She is the author of two novels: Anonymous Sources and The Bullet.

Marion Downs Appreciation

By Amy Gross

I had no idea how influential Marion Downs had been—and at the time, still was—regarding newborn infant screening, but it didn't take much research to discover that this woman was a big, big deal. I don't know why, but her passing on November 13, 2014, caught me by surprise. It didn't matter that she had reached her 100th birthday; I, like many of her fans, found it difficult to accept that the force known as Marion Downs had moved on, peacefully, in her sleep.

Marion (she wouldn't let me call her "Ms. Downs") was 92 when we spoke. She was still skiing and swimming and playing tennis competitively, and one of the photos in “Shut Up and Live!” showed her gleefully skydiving with a handsome young instructor (she made sure to point out the "handsome" part several times). I had read every word of her book, in which she provided candid advice for anyone dealing with the aging process: the importance of weight training, why hearing aids are critical in the health of a marriage, and how to maintain a healthy sex life into one's senior years. I loved that she was able to make me blush more than a few more times; the woman minced no words.

What had put Marion Downs on the map, audiologically speaking, were her pioneering efforts, beginning in the early 1960s, in the essentially unheard-of area of infant hearing testing. An audiologist herself, Marion and a research partner started hearing testing for newborns before those infants had even left the hospital, fitting even the tiniest babies with hearing aids. Today, thanks to Early Hearing and Detection Intervention programs, 97 percent of newborns have their hearing screened. Knowing what we know today about the importance of hearing with respect to language and even cognitive development in extremely young children, there's no telling how many infants with hearing loss were identified as such in a timely manner, and their developmental skills saved, because of Marion Downs's work.

The Marion Downs Center in Denver, Colorado, a nonprofit organization that espouses, as Marion did herself, a cradle to grave approach in dealing with hearing loss, will continue her efforts in advocating for those with hearing loss. Marion was a visionary in the world of hearing health. Her legacy lives on, quite visibly, in the children whose lives she touched.