By Peter G. Barr-Gillespie, Ph.D.

A DNA double helix

National Human Genome Research Institute

Recently, Hearing Health Foundation (HHF) has received several questions regarding the Reuters report on gene therapies for hearing. There are two separate but related topics raised in this article. As the scientific research director of HHF’s Hearing Restoration Project, which since 2011 has been uncovering concrete discoveries toward a biologic cure for hearing loss and tinnitus, I want talk about each individually, and then discuss what I interpret they mean together.

The article first presents the Science Translational Medicine paper from Jeffrey Holt’s lab. This is very much a proof-of-principle report, focused on an animal model and using a time for delivery of the corrected gene that is extremely early in development (equivalent to a 5-to-6-month-old human fetus). It is important to point out that their strategy will only correct one type of genetic hearing loss and genetic hearing loss from mutations in other genes will require related but different strategies. Nevertheless, this is an exciting example of modeling gene therapy in animals, and represents a logical progression toward that goal in humans.

The article then moves on to reference the Novartis trial. For this trial, they are using a similar technical strategy, viral delivery of a gene, but they are targeting people—those who have lost their hearing through non-genetic means, such as noise damage, aging, or infections. The gene they are delivering, known as ATOH1, may stimulate production of new hair cells; it is a gene that is essential for formation of hair cells during development, and in some experimental animal models, delivery of the gene can lead to production of a few hair cells in adult ears.

That said, many people who I have talked to in the field who work with experimental models of hair cell formation using ATOH1, including members of our Hearing Restoration Project consortium, believe that this trial is premature. By and large, the animal models do not support the trial; most suggest that there will be few hair cells formed and little hearing restored. While we can hope for a little bit of hearing recovery, we are concerned about toxic responses to the gene delivery using viruses. Personally, while I think it would be truly fantastic if the Novartis trial works, at this moment in time I don’t think the rewards yet outweigh the considerable risks being imposed on a human (include safety during the procedure and potential side effects afterward).

Still, the Novartis trial will tell us about the safety of viral delivery into the ears of humans, and knowing that is critically important. I think the most likely outcome is that we will learn whether the strategy the Novartis trial used to deliver the gene is safe. Unfortunately, if we don’t see improved hearing, we won’t know why—did the gene not get to the right place, or does it just not work?

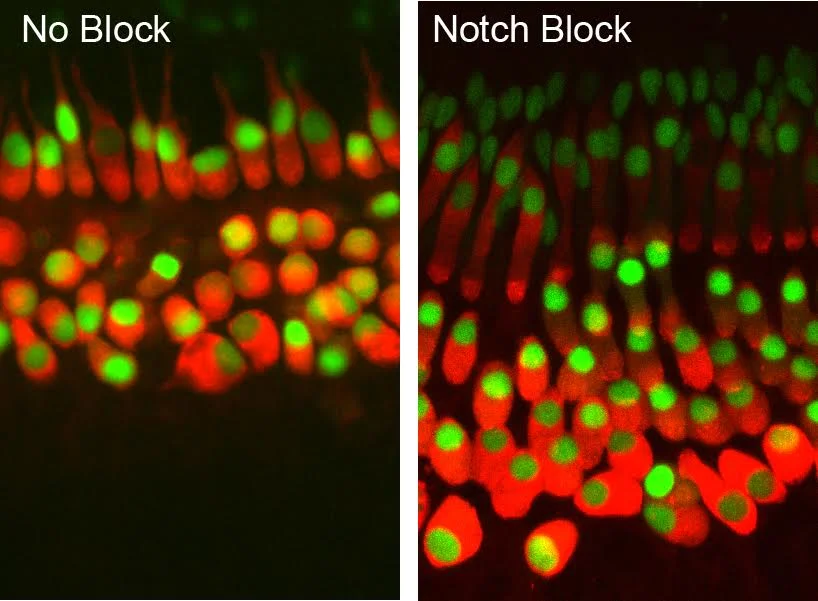

Technical aspects of gene delivery are what ties together the Novartis work and the Holt lab work. Both use viruses for delivering genes, and together the results from these and others will let us know, from a procedural standpoint, how we can deliver genes to the ear. I think it is unlikely that delivering just ATOH1 will do the trick of restoring hearing; it may be that we need to deliver other genes or to use drugs to overcome the block we see to making new hair cells.

So while these are exciting reports to hear about, especially that Novartis is actually carrying out a trial in humans, it is still premature to think that this is going to be a viable strategy for restoring hearing. This is why Hearing Health Foundation's Hearing Restoration Project is doing everything possible to accelerate the pace of its research.

Hair cell regeneration is a plausible goal for the treatment of hearing and balance disorders. The question is not if we will regenerate hair cells in humans, but when. Your financial support will help to ensure we can continue this vital research and find a cure in our lifetime! Please help us accelerate the pace of hearing and balance research and donate today. Your HELP is OUR hope!

If you have any questions about this research or our progress toward a cure for hearing loss and tinnitus, please contact Hearing Health Foundation at info@hhf.org.