Multiple key guitars from Les Paul’s collection are in The Les Paul House of Sound. Hands-on activities guide visitors to explore the science of sound.

Despite Challenges, Les Paul Persevered

Les Paul persisted to refine the design for a solid body electric guitar, create multiple gold records, invent today’s recording techniques, be inducted into multiple halls of fame, and play his guitar until two months before he died at 94 years old in August 2009.

New Sounds, Thanks to Les Paul

The inventor of today’s recording techniques—with multiple ways to manipulate sound—would have been 109 this June 9. That would be Les Paul, the man whose signature is blazoned on the famous Gibson guitar.

Les Paul Was Dedicated to Veterans

Like most men during World War II, Les Paul was drafted into the U.S. Armed Forces, where he held three positions in the Armed Forces Radio Service.

High-Energy Les Paul Took to the Road to Perform

Les Paul was born on June 9, 1915, and each June we celebrate this legendary artist who did so much to change the face of music, and to express our gratitude to the Les Paul Foundation for their support of the Emerging Research Grants program.

The Enduring Legacy of Les Paul in Music and Science

Since 2014 the Les Paul Foundation has funded six Emerging Research Grants on tinnitus, deepening our understanding of its causes as well as improving diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

How Les Paul’s Mother Nurtured Him to Change the Music Industry

Even when Les Paul was a preschooler, his mother Evelyn recognized his talent. She would arrange for her young son to perform for local fraternal organizations. Les was so tiny that they placed him on top of a table where he would sing, dance, and tell funny stories.

From a $3.95 Guitar to the Solid Body Electric Guitar: How Les Paul’s Persistence Changed the World of Music

Music legend Les Paul is famous for inventing the solid body electric guitar and other innovations related to recording music. Less known is that he also had a hearing loss and wore hearing aids in both ears.

The Man Who Chased Sound Wore Hearing Aids

Legendary musician Les Paul spent his whole life looking for the perfect sound. Ironically, for a good portion of his life he had to pursue his passion for sound while wearing hearing aids.

Disrupted Nerve Cell Function and Tinnitus

By Xiping Zhan, Ph.D.

Tinnitus is a condition in which one hears a ringing and/or buzzing sound in the ear without an external sound source, and as a chronic condition it can be associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. Tinnitus has been linked to hearing loss, with the majority of tinnitus cases occurring in the presence of hearing loss. For military service members and individuals who are constantly in an environment where loud noise is generated, it is a major health issue.

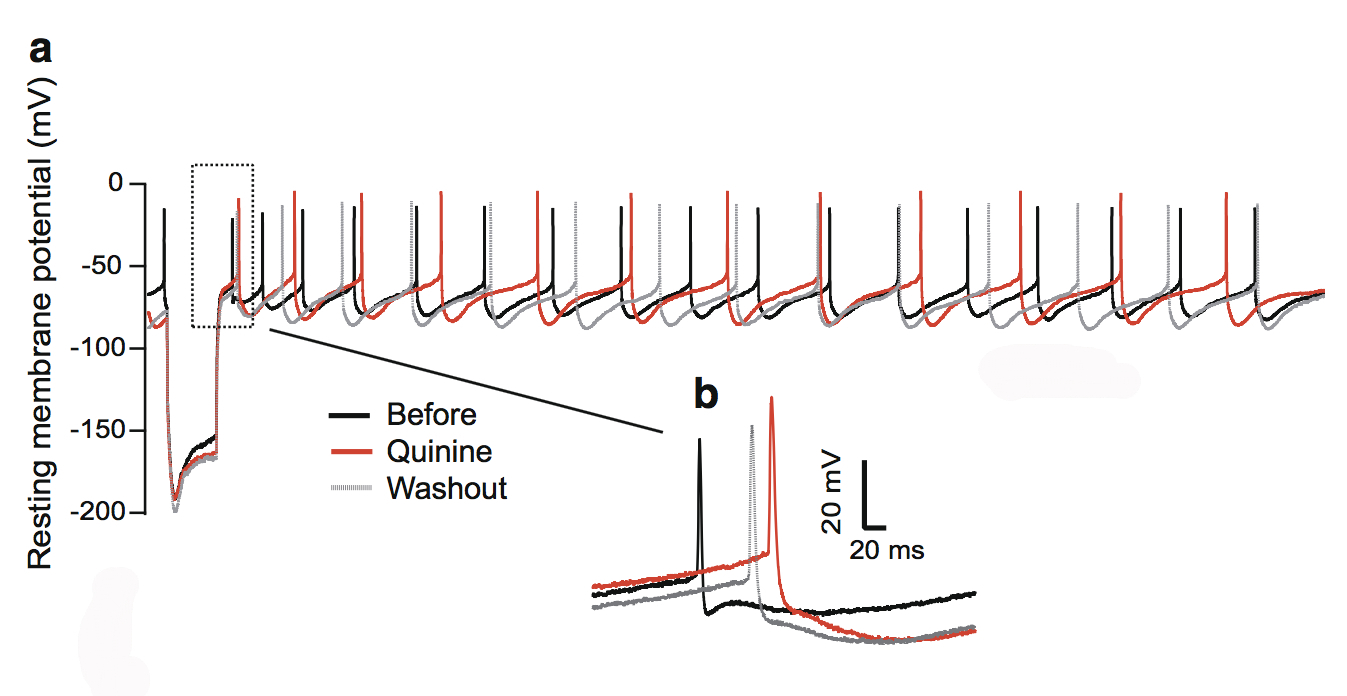

This figure shows the quinine effect on the physiology of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, a structure in the midbrain.

During this phantom ringing/buzzing sensation, neurons in the auditory cortex continue to fire in the absence of a sound source, or even after deafferentation following the loss of auditory hair cells. The underlying mechanisms of tinnitus are not yet known.

In our paper published in the journal Neurotoxicity Research in July 2018, my team and I examined chemical-induced tinnitus as a side effect of medication. Tinnitus patients who have chemical-induced tinnitus comprise a significant portion of all tinnitus sufferers, and approaching this type of tinnitus can help us to understand tinnitus in general.

We focused on quinine, an antimalarial drug that also causes hearing loss and tinnitus. We theorized this is due to the disruption of dopamine neurons rather than cochlear hair cells through the blockade of neuronal ion channels in the auditory system. We found that dopamine neurons are more sensitive than the hair cells or ganglion neurons in the auditory system. To a lesser extent, quinine also causes muscle reactions such as tremors and spasms (dystonia) and the loss of control over body movements (ataxia).

As dopaminergic neurons (nerve cells that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine) are implicated in playing a role in all of these diseases, we tested the toxicity of quinine on induced dopaminergic neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells and isolated dopaminergic neurons from the mouse brain.

We found that quinine can affect the basic physiological function of dopamine neurons in humans and mice. Specifically, we found it can target and disturb the hyperpolarization-dependent ion channels in dopamine neurons. This toxicity of quinine may underlie the movement disorders and depression seen in quinine overdoses (cinchonism), and understanding this mechanism will help to learn how dopamine plays a role in tinnitus modulation.

A 2015 ERG scientist, Xiping Zhan, Ph.D., received the Les Paul Foundation Award for Tinnitus Research. He is an assistant professor of physiology and biophysics at Howard University in Washington, D.C. One figure from the paper appeared on the cover of the July 2018 issue of Neurotoxicity Research.

We need your help supporting innovative hearing and balance science through our Emerging Research Grants program. Please make a contribution today.