By Scott Swanson

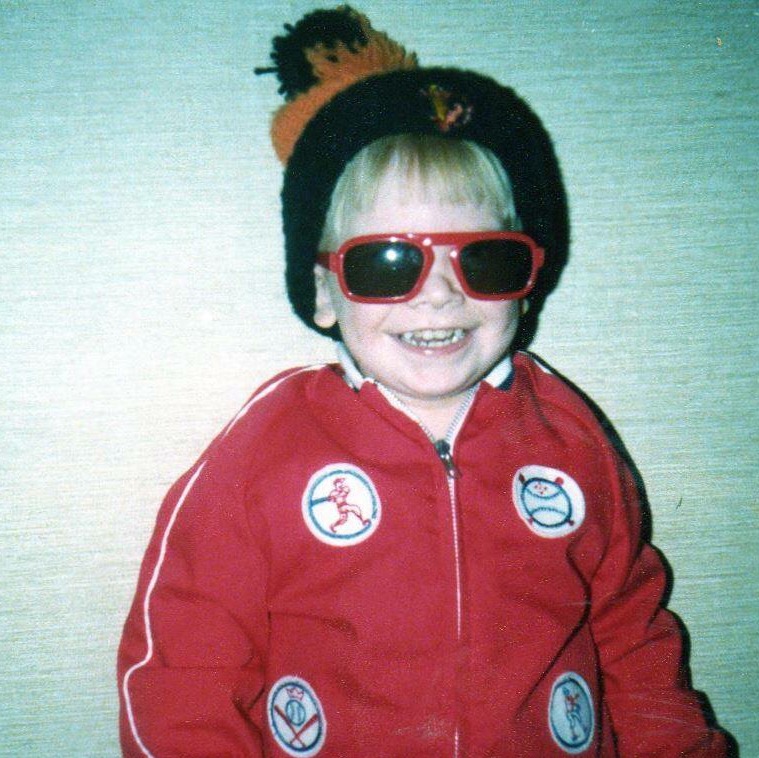

It's 1982. I'm 4 years old, and the proud new owner of two behind-the-ear hearing aids. These things are monsters. Huge. A result of life-saving surgery I had two years earlier. My mother had to put them in for me every morning. At age 4, I had no clue that this stinks.

In 1983 I started kindergarten. In the Pacific Northwest, where I live, rain is a way of life. You don't duck for cover just because there's precipitation in the air. This especially goes for recess. At my school, there was this woman we called "Grandma" whose job it was to oversee the playground. She was old, and she laid down the law. She also rewarded kids who picked up toys with sugar-free candies. Those things were the worst! But some of us enjoyed the nice gesture.

One fine September day it was raining and as usual, we got sent to the playground. I was getting pretty deep into a game of Foursquare, or maybe it was Red Rover. Either way, I find myself being sent inside by Grandma. Back to my classroom I went. I'm pretty sure I thought I was in trouble. Was I hogging the ball? Being mean? I couldn't figure it out.

School ended later that day, and I walked home in the rain. I remember when I walked through the front door my mom and dad were chuckling. They asked me how my day was. I gave them a generic response: "Fine.” "How was recess?" "Dumb." "Why?" "Grandma sent me back to my classroom for no reason." More chuckles, and then my mom told me to have a seat.

She told me that the school called to say they very concerned for my safety. She explained to me that Grandma noticed my hearing aids. She also noticed the rain. She put two and two together. When water and electronics mix, people get electrocuted. Grandma must have thought she saved my life. My parents told the school that although they appreciated them erring on the side of caution, I was not in danger of being electrocuted. A little rain would at worst damage my hearing aids but definitely not cause me to lose my life.

I still see Grandma from time to time in the grocery store. I think back to that day and I doubt she remembers. She was old to us then, let alone 25 years later. Most importantly, I know she had my safety on her mind, and for that I'm thankful. I'll always remember her as much as any teacher I had at that school. Gross sugar-free candies, and all!

Scott has moderate to severe hearing loss. At age two, while undergoing life-saving surgery, Scott was administered ototoxic antibiotics, which have a side effect of hearing loss. By the age of four Scott had enough hearing loss to require hearing aids. He initially wore behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aids, but currently wears completely-in-canal (CIC) hearing aids. Scott is the only one in his family that lives with hearing loss.