By Keck Medicine of University of Southern California

Exposure to loud noise, such as a firecracker or an ear-splitting concert, is the most common preventable cause of hearing loss. Research suggests that 12 percent or more of the world population is at risk for noise-induced loss of hearing.

Loud sounds can cause a loss of auditory nerve cells in the inner ear, which are responsible for sending acoustic information to the brain, resulting in hearing difficulty. However, the mechanism behind this hearing loss is not fully understood.

Now, a new Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology study from Keck Medicine of University of Southern California (USC) links this type of inner ear nerve damage to a condition known as endolymphatic hydrops, a buildup of fluid in the inner ear, showing that these both occur at noise exposure levels people might encounter in their daily life.

Additionally, researchers found that treating the resulting fluid buildup with a readily available saline solution lessened nerve damage in the inner ear.

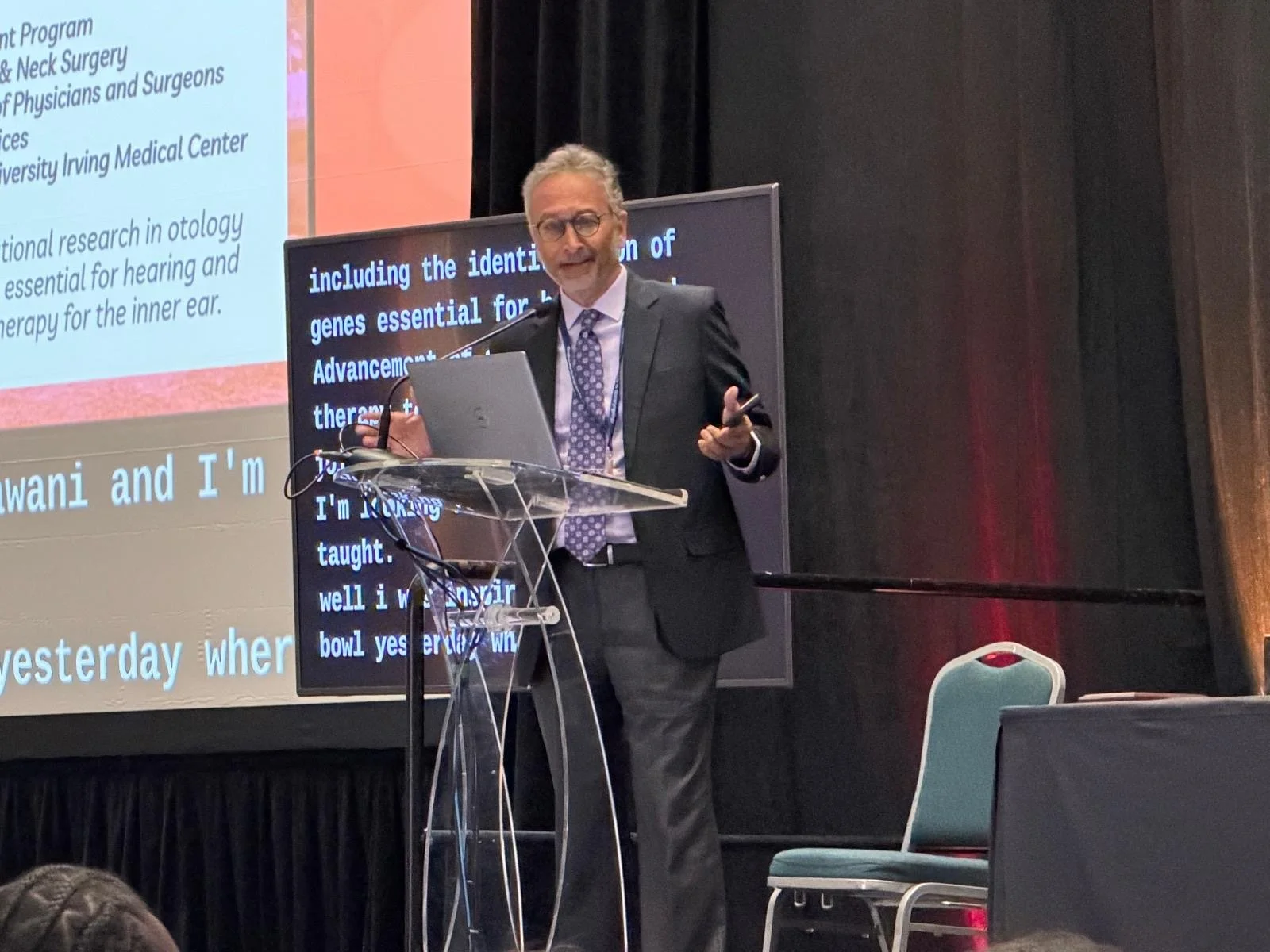

“This research provides clues to better understand how and when noise-induced damage to the ears occurs and suggests new ways to detect and prevent hearing loss,” says John Oghalai, M.D., an otolaryngologist with Keck Medicine, the chair of the USC Caruso Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and the lead author of the study.

A previous study by Oghalai conducted on mice exposed to blast pressure waves simulating a bomb explosion linked nerve damage with fluid buildup in the inner ear.

For this study, Oghalai and colleagues wanted to explore the effect of common loud sounds ranging from 80 to 100 decibels (dB) on the mouse inner ear. After the exposure, they used an imaging technique known as an optical coherence tomography to measure the level of inner ear fluid in the cochlea, the hollow, spiral-shaped bone found in the inner ear.

Up until exposure to 95 dB of sound, the inner ear fluid level remained typical. However, researchers discovered that after exposure to 100 dB—which is equivalent to sounds such as a power lawn mower, chainsaw, or motorcycle—the mice developed inner ear fluid buildup within hours. A week after this exposure, the mice were found to have lost auditory nerve cells.

However, when researchers applied hypertonic saline, a salt-based solution used to treat nasal congestion in humans, into the affected mouse ears one hour after the noise exposure, both the immediate fluid buildup and the long-term nerve damage lessened, implying that the hearing loss could be at least partially prevented.

These study results have several important implications, according to Oghalai, especially as the loss of nerve cells in the inner ear is known as “hidden hearing loss” because hearing tests are unable to detect the damage.

“First, if human ears exposed to loud noise, such as a siren or airbag deployment, can be scanned for a level of fluid buildup—and this technology is already being tested out—medical professionals may have a way of diagnosing impending nerve damage,” he says. “Secondly, if the scan discovered fluid buildup, people could be treated with hypertonic saline and possibly save their hearing.”

Oghalai also believes the study opens a new window into understanding Ménière’s disease, a disorder of the inner ear that causes vertigo, ringing in the ears (tinnitus), and hearing loss.

“Previously, inner ear fluid buildup was thought to be primarily linked to Ménière’s disease. This study indicates that people exposed to loud noises experience similar changes,” he says.

Credit: Ricardo Carrasco III

Oghalai hopes this study will lead to further research on the reasons ear fluid buildup occurs, and encourage the development of better treatments for Ménière’s disease.

This originally appeared at news.keckmedicine.org. John Oghalai is a 1996–1997 Emerging Research Grants scientist. The study was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

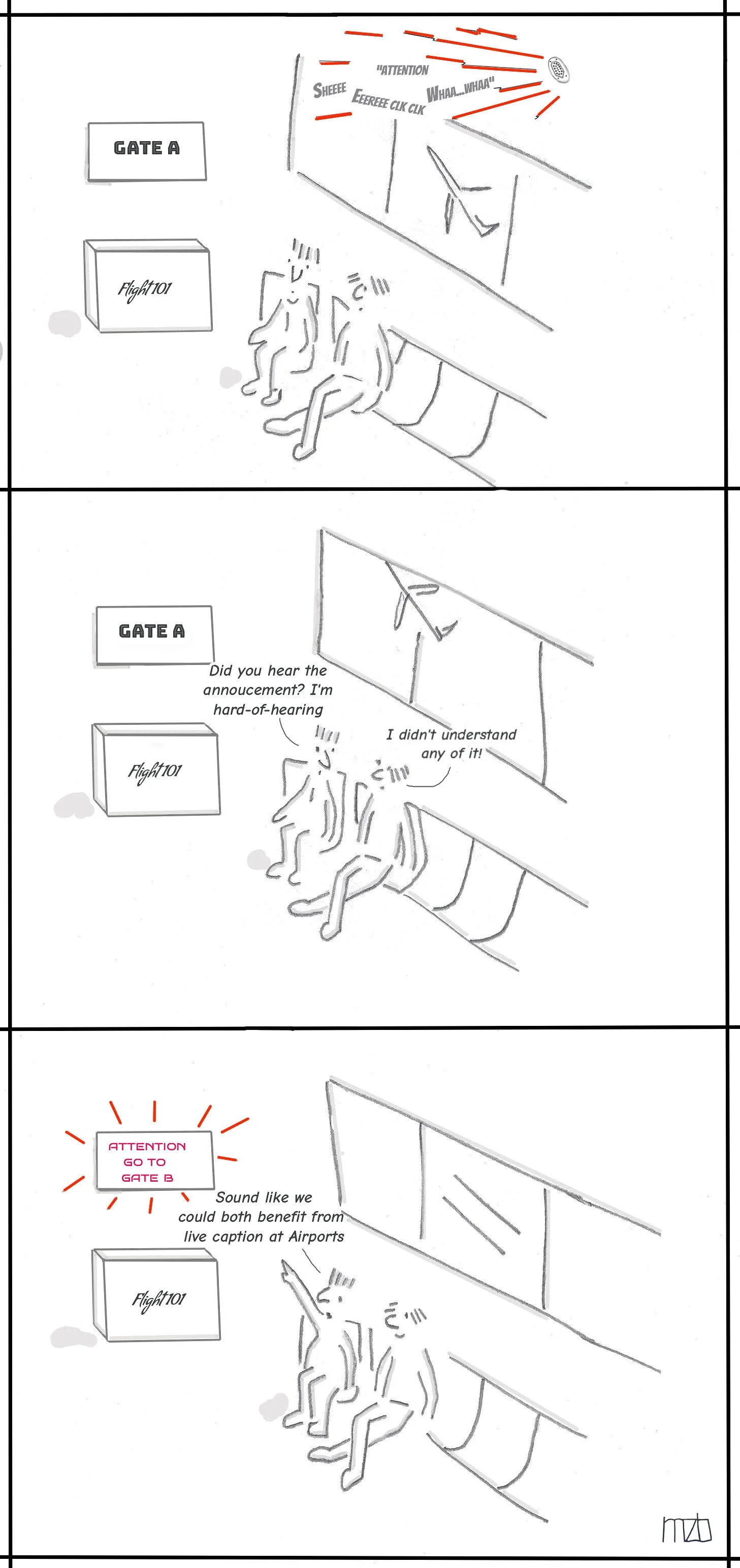

Our new public service announcement “Let’s Listen Smart” recognizes that life is loud—and it’s also fun. And the last thing we want to do is stop having fun! We just need to listen responsibly.