By Emily Fabrizio-Stover, Ph.D., James Dias, Ph.D., and Carolyn McClaskey, Ph.D.

As we get older, it can become more difficult for the auditory nerve to transmit sounds to the brain. Despite this difficulty, the brain’s response to sound can be amplified in older adults. This amplified response in the brain has been linked to a common age-related hearing difficulty: understanding speech in noisy environments. It is unknown whether these amplified responses occur somewhere between the ear and the brain, such as the brainstem.

Using electroencephalography (EEG) to measure neural responses to sound, we examined how neural responses changed as information traveled from the auditory nerve, the structure that carries information away from the ear, to the auditory cortex.

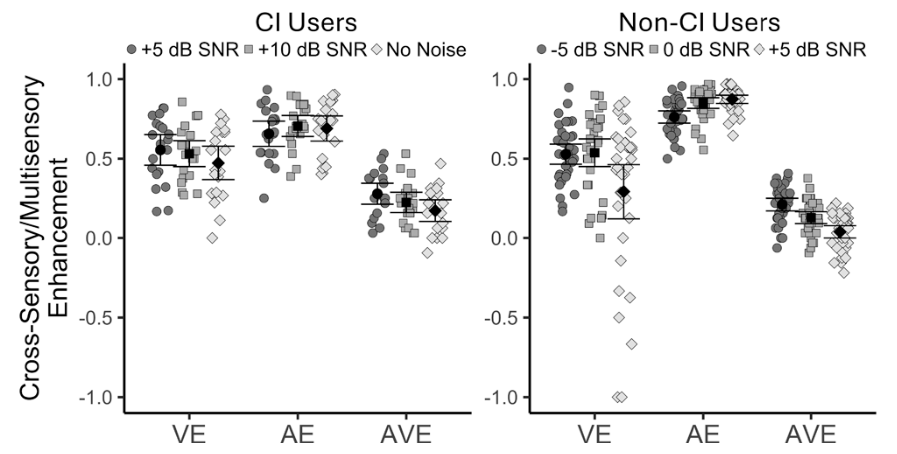

We found that at the auditory nerve, older adults had smaller responses than younger adults. As the signal traveled up the auditory pathway to the brain, responses in older adults progressively increased. At the level of the auditory cortex, older adults showed larger responses than younger adults. This suggests that the aging brain is amplifying its response to compensate for weaker input from the ear, demonstrating progressive “central gain.”

Hypothesized pattern of central gain through the levels of the auditory pathway. Our data support a pattern of central gain in older adults from the auditory brainstem to the auditory cortex. Shown here, we find that weaker auditory nerve (AN) signals in older adults lead to typical-sized responses in the brainstem and stronger than normal responses in the auditory cortex. Younger = red, older = black. Credit: Fabrizio-Stover et al./Neurobiology of Aging

The changes in brain structure underlying amplified responses to sound in older adults are not known. To study the relationship between amplified responses and brain structure, we used a type of magnetic resonance imaging that measures how water moves in the brain areas that receive sound input from the ear (auditory cortex). Water movement in the brain is used as a measure of structural integrity because brains with intact cells and supporting structures have more directional water flow than brains with poor structural integrity.

We discovered that older adults had worse brain integrity overall when compared with younger adults. When we combined EEG and brain imaging data in older adults, we saw that older adults with poorer auditory cortex integrity had amplified neural responses to sound and also more trouble understanding speech in noisy environments, when compared with older adults with better auditory cortex integrity.

Overall, we found that the aging brain tries to amplify degraded input from the auditory nerve and that amplified responses are associated with poorer brain structure and trouble with speech understanding. These results, which we published in the journal Neurobiology of Aging in November 2025, are important because they show that this amplified response may impair speech understanding in noisy environments. Next, we want to study if these amplified brain responses may still provide benefits for other aspects of hearing.

Emily Fabrizio-Stover, Ph.D. (top left), is a postdoctoral fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC).

Coauthors James Dias, Ph.D. (center left), and Carolyn McClaskey, Ph.D. (bottom left), are Emerging Research Grants scientists also at MUSC. Dias’s 2022–2023 grant was generously funded by the Meringoff Family Foundation, and McClaskey’s 2023–2024 grant was generously funded by Royal Arch Research Assistance.

See their paper (also coauthored by Kelly C. Harris, Ph.D., of MUSC), “Age-related auditory nerve deficits propagate central gain throughout the auditory system: Associations with cortical microstructure and speech recognition,” in the journal Neurobiology of Aging, published in November 2025.

Because noise-canceling earbuds are so comfortable and block everything out, people wear them for three, four, five hours straight without realizing the cumulative effect on their ears.