Cochlear implantation has one of the most favorable risk–benefit ratios of any surgical procedure in the U.S., offering significant communicative benefit while incurring little risk.

Shared Knowledge Is Power

ARO provides auditory and vestibular researchers opportunities present their latest findings and engage in meaningful conversations with one another. If one scientist presents an idea to an audience of 100 scientists, she’s just created the possibility for 100 new ideas will form.

It's Good to Hear: A March 3 Call to Action

Good to Hear aligns with the celebration of World Hearing Day―the World Health Organization (WHO)’s annual March 3 campaign to raise awareness of hearing loss care and prevention. On a day when all eyes will already be on our ears, HHF is determined to engage as many supporters as possible to empower scientific progress.

Flying My Way

My longtime fascination with all things aerospace inspired my desire to work with computers for a living. But, at times, my hearing and vision loss caused some turbulence.

Making Friends and Influencing People

By Kathi Mestayer

Lorrie Moore, the author of “Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?” was in town in Williamsburg, Virginia, giving a reading at Tucker Hall at the College of William and Mary. My friend Susan had invited me, and I actually remembered the author’s name and knew that book was somewhere on my shelf, so I said yes.

My husband Mac had read the book, and was sure I would like it. I managed to find it on our jumbled bookshelves, which are kind of in alphabetical order (for fiction, at least). And it was short, only 147 pages! Before long, I realized that I had already read it, too. Not because I remembered anything, mind you, but because my marks and scars were present pencil lines in the margins, and a few dog-eared pages. Mac never marks up a book, or dog-ears the pages, and it drives him crazy when I do. So, it’s usually easy to tell whether I’ve read a book. In this case, I was probably walking that fine line with my fine lines.

I got 33 pages into the book, and it was lively stuff. One passage I had circled (in ink!) was, “She inhaled and held the smoke deep inside, like the worst secret in the world, and then let it burst from her in a cry.” I love revisiting a book, like a stone skipping over water, hitting the high spots thanks to my notes.

So when the day of the reading arrived, I went to listen to Lorrie Moore read her favorite passages in her own voice.

Wishful Thinking

When I got to the lecture hall, I sat by Susan, who was fortunately in the second row, near the aisle. Someone introduced Lorrie Moore. I couldn’t hear most of that, but it didn’t really matter. Then she got up to read, holding a big, thick book (her latest), with a microphone clipped to her lapel.

I couldn’t hear a word of it. It seemed as though she was muttering softly, but I’m not a good judge of that. I leaned over and whispered to Susan that I was having trouble hearing and was going to sit in the front row. Well, Susan outed me immediately, and informed the guy who had introduced Lorrie that she wasn’t audible. While I tried to surreptitiously move to the very center of the front row, he asked Lorrie to hold the lapel mic in her hand, so it could be closer to her mouth.

She did that for a few minutes, but it got awkward when she needed to hold the book, too. And when she held the mic in her hand, it was so close to her mouth that her speech was distorted, with the P’s and T’s sounding like balloons popping. Tiny balloons, but enough to muddy her speech. For me.

So, at the suggestion of a young man on my right, she put the mic back on her lapel, but closer to her face. She asked, “Can everyone hear me now?” I didn’t turn around to see the response behind me, but it was clear that she got some no’s because she started playing around with the mic and saying, “How about now?” And, “Now?”

That was when one of the professors leapt over the front two rows, got on the stage, took the big, regular-mic holder (which was empty), bent it around to the front of the lectern, and clipped the tiny lapel mic to it. Okay. It was closer to her mouth, and she could use her hands for other things.

Let the reading begin. Again.

This time, she read for about 20 minutes, and I still couldn’t hear clearly enough to know what she was mumbling into the mic, with the P’s and T’s popping again due to its proximity to her mouth. I sat there patiently, not wanting to be disruptive again, and thought about other things, in between the audience’s intermittent chuckling. To my credit, I did not get my phone out to check my email.

After she was done, and the Q&A period started, I slunk out of the room, as quietly as possible. Others were doing the same, so I felt a little less rude. The next day, I got an apologetic email from Susan.

Not Just Me

A couple of days later, I was in a gift shop downtown, and a young woman behind the counter asked if I had been at the reading the other night in Tucker Hall. I said yes. Turns out, she was sitting right behind me. When I mentioned that I had a really hard time hearing in that space, she replied, “Oh, I HATE that room! It’s the worst one on campus! I can never hear in there.”

The good news is that, the next time Susan invited me to a reading, she made a point of saying they had gotten the good mic back up and running. And, in fairness, making an entire campus of classrooms and other spaces hearing-friendly will take time, money… and attention. In fact, I’ve already managed to get an FM system installed in two auditoriums in another building on campus. So, slowly, the system is getting better, one complaint at a time.

I think of that passage I ink-circled, about inhaling smoke like a big secret and letting it burst forth. Advocating to hear can put you in the spotlight, uncomfortably, especially in a group situation, but we should let our needs burst forth to help others who are no doubt in the same situation.

Kathi Mestayer is a staff writer for Hearing Health magazine.

Helping Myself to Help Others

By Ryan Brown

My hearing loss was identified around the time I started kindergarten. I started asking “what?” a lot, and I didn’t always respond to those around me. Some of my teachers thought I was ignoring them or missing instructions on purpose. At home I began to sit closer to the TV with the volume up high.

Subtle behaviors like this in a child can sometimes go undetected, much like those of a student who struggles because he can’t read the board in the classroom. Thankfully, a teacher finally noticed that I was reading her lips and recommended that I see a speech-language pathologist. Eventually, I was referred to an audiologist, Sheila Klein, Au.D. She diagnosed me with moderate to severe bilateral hearing loss, most likely caused by recurrent ear infections when I was younger.

My mom distinctly remembers leaving Dr. Klein’s office with my new hearing aids. After we walked out the door into the parking lot, I took a few steps, stopped and looked around, then walked a few more. This was the first time I heard my jacket make a whoosh sound as I moved. I spent a lot of time that day hearing new things I had never noticed before.

Soon after that, Dr. Klein came to visit my school. She explained to my classmates what it means to have a hearing loss and why I needed hearing aids. I really appreciate this gesture because it encouraged my classmates to be more accepting of someone who was different than them.

One of my favorite hobbies is music, and hearing aids have been instrumental to helping me understand and practice it. I enjoy creating electronic songs using a production software called Ableton, which provides a means of arranging music as well as a visual representations of sound waves. This tool is crucial because there are certain frequencies I simply cannot hear, and people without hearing loss may hear harsh noises that disrupt the sound I was aiming for. This feature allows me to filter those sounds out visually. Without my hearing aids, I would have a hard time noticing these details in the final product.

I am in my third year of medical school, pursuing a career in Emergency Medicine. I spend most of my days assisting and learning from physicians at hospitals and clinics. The purpose of this training is to eventually be able to practice and treat patients on my own.

My aspiration to work in medicine came about during junior year of high school, when I sought help from my local Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) office. VR counselors provide career assistance to people with disabilities. Medicine requires one to use a stethoscope, so the VR counselors found an electronic stethoscope and headphones I could fit over my hearing aids. The headphones can be confusing for patients sometimes, but they understand once I start listening to their heart and lungs.

I’ve really enjoyed learning about the art and science of medicine. Problem solving and building a trustworthy relationship with a patient are crucial skills which I will continue to develop for the rest of my life.

The impact my hearing aids have had in my development cannot be understated, but communication is still difficult at times even with them in. I have learned to be patient and understand that not everyone knows what it’s like to have hearing loss or wear devices like hearing aids. Sometimes there is a need for others to speak up or face me so that I can read their lips, especially in crowded places. Having to overcome challenges like this has instilled an important trait that is essential in medicine: empathy.

Ryan William Brown is a student at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine.

New Insights into the Development of the Hair Cell Bundle

By Yishane Lee

Recent genetic studies have identified that the protein Ripor2 (formerly known as Fam65b) is an important molecule for hearing. It localizes to the stereocilia of auditory hair cells and causes deafness when mutations disrupt its function.

In a study published in the Journal of Molecular Medicine in November 2018, Oscar Diaz-Horta, Ph.D., a 2017 Emerging Research Grants (ERG) scientist, and colleagues further show the role the protein plays by demonstrating how it interacts with other proteins during the development of the hair cell bundle. The team found that the absence of Ripor2 changes the orientation of the hair cell bundle, which in turn affects hearing ability.

Ripor2 interacts with Myh9, a protein encoded by a known deafness gene, and Myh9 is expressed in the hair cell bundle stereocilia as well as its kinocilia (apices). The team found that the absence of Ripor2 means that Myh9 is low in abundance. In the study, Ripor2-deficient mice developed hair cell bundles with atypically localized kinocilia and reduced abundance of a phosphorylated form of Myh9. (Phosphorylation is a cellular process critical for protein function.)

Another specific kinociliary protein, acetylated alpha tubulin, helps stabilize cell structures. The researchers found it is also reduced in the absence of Ripor2.

The study concludes that Ripor2 deficiency affects the abundance and/or role of proteins in stereocilia and kinocilia, which negatively affects the structure and function of the auditory hair cell bundle. These newly detailed molecular aspects of hearing will help to better understand how, when these molecular actions are disrupted, hearing loss occurs.

A 2017 ERG scientist funded by the Children’s Hearing Institute (CHI), Oscar Diaz-Horta, Ph.D., was an assistant scientist in the department of human genetics at the University of Miami. He passed away suddenly in August 2018, while this paper was in production. HHF and CHI both send our deepest condolences to Diaz-Horta’s family and colleagues.

We need your help supporting innovative hearing and balance science through our Emerging Research Grants program. Please make a contribution today.

How Ménière's Led Me to a Master’s

By Anthony M. Costello

Ménière's disease initially presented itself to me 20 years ago in a violent and unfortunate manner. I was 16 attending a New England boarding school when I experienced a vestibular (balance) episode, and it changed my health and life forever.

I remember vividly the vertigo that, without warning, controlled me. I remember the incredible pressure and fullness in my ears and the overwhelming sense of nausea. Realizing I could not stand I sought refuge in my bed, where the sensation of spinning intensified and I vomited profusely.

The school staff could only assume I was intoxicated and took disciplinary action. As I could not yet explain or understand that my behavior was caused by Ménière's disease, I had little recourse to justice. Faced by more unfair treatment, I left the school at the end of the academic year.

For the remainder of high school, I continued to struggle with bouts of vertigo, dizziness, and imbalance. These symptoms impacted my athletic performance, my ability to concentrate on my schoolwork, and my general quality of life. It was a difficult and confusing time as I appeared fine on the outside but I was internally battling a miserable existence that I could not fully understand or control. That paradox has since defined my life.

Shutterstock

When I received a formal diagnosis, my thoughts, priorities, and routines obsessively revolved around managing my wellness. This new mindset made it difficult to relate to the life I once had or to the lives of those around me. I made great efforts to hide my symptoms and protect loved ones from the negative emotional and physical effects of my disease. I made excuses to avoid social events just because of my illness.

Ménière's disease has repeatedly left me in states of hopeless despair. While it can be perceived as “strong” to persevere through one’s condition independently, I have learned this only leads to more isolation. Ménière's takes so much from its sufferers; it attacks their bodies, tests their spirits, and consumes their thoughts. This is why it is so important to reach out, be honest, and bring others into your world that you trust while you are living with Ménière's. Otherwise, you deprive yourself of not only your health but the relationships you deserve.

The etiology of Ménière's disease remains scientifically disputed and I do not claim to have the answer. But I do know the condition does not respond well to stress. I’ve spent every day of my life carefully crafting my decisions and actions based on how my Ménière's may react. In the process, I’ve come to master handling and mitigating stress. In fact, at 30 I went back to school for a master’s in psychotherapy in part to study stress and the human mind. I now licensed psychotherapist, a career change inspired by my conversations with newly diagnosed Ménière's patients in the waiting room of my ear, nose, and throat doctor’s office.

I have been fortunate to have had periods of relative remission with reduced vertigo. But there is a misconception that Ménière's just comes and goes, allowing the sufferer to return to normalcy in the interim. In reality, part of it is always there, be it the tinnitus, the difficulty hearing people in a crowded room, or the feeling the floor will start moving. There is always the uncertainty of what tomorrow will bring.

Using mindfulness—a meditation technique that helps one maintain in the present without judgment—has been helpful in calming my anxiety. Mindfulness is especially useful when my tinnitus feels overwhelming, and I sometimes I combine the practice with music, a white noise machine, or masking using a hearing aid.

I try to live my life in a manner in which Ménière's never wins. This disease will bring me to my knees—both literally and figuratively—but I just keep getting up. You can’t think your way out of this disease and spending all your time in a web of negative thoughts can be as toxic to your mind as Ménière's is to your inner ears. In my hopelessness, I try to stop my mind from plunging into the abyss and use every tool I can—making plans see friends and family, finding glimpses of joy in the midst of darkness, or being physically active. You have to retain some control when you feel like you have none.

The only gift that Ménière's has given me is a level of introspection and awareness that I could not have attained in 10 lifetimes. It has stripped me down to my core and forced me to explore what is truly important and made me a better person. I don’t know who I would be without this disease, but I’m positive that person could not fathom the joy or gratitude I find in a moment of health.

Anthony M. Costello, LMFT, lives in Byfield, Massachusetts with his wife, daughter, and 2 dogs. He has a private practice and specializes in helping others with chronic illness. For more, see www.costellopsychotherapy.com.

Receive updates on life-changing hearing and balance research, resources, and personal stories by subscribing to HHF's free quarterly magazine and e-newsletter.

Disrupted Nerve Cell Function and Tinnitus

By Xiping Zhan, Ph.D.

Tinnitus is a condition in which one hears a ringing and/or buzzing sound in the ear without an external sound source, and as a chronic condition it can be associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. Tinnitus has been linked to hearing loss, with the majority of tinnitus cases occurring in the presence of hearing loss. For military service members and individuals who are constantly in an environment where loud noise is generated, it is a major health issue.

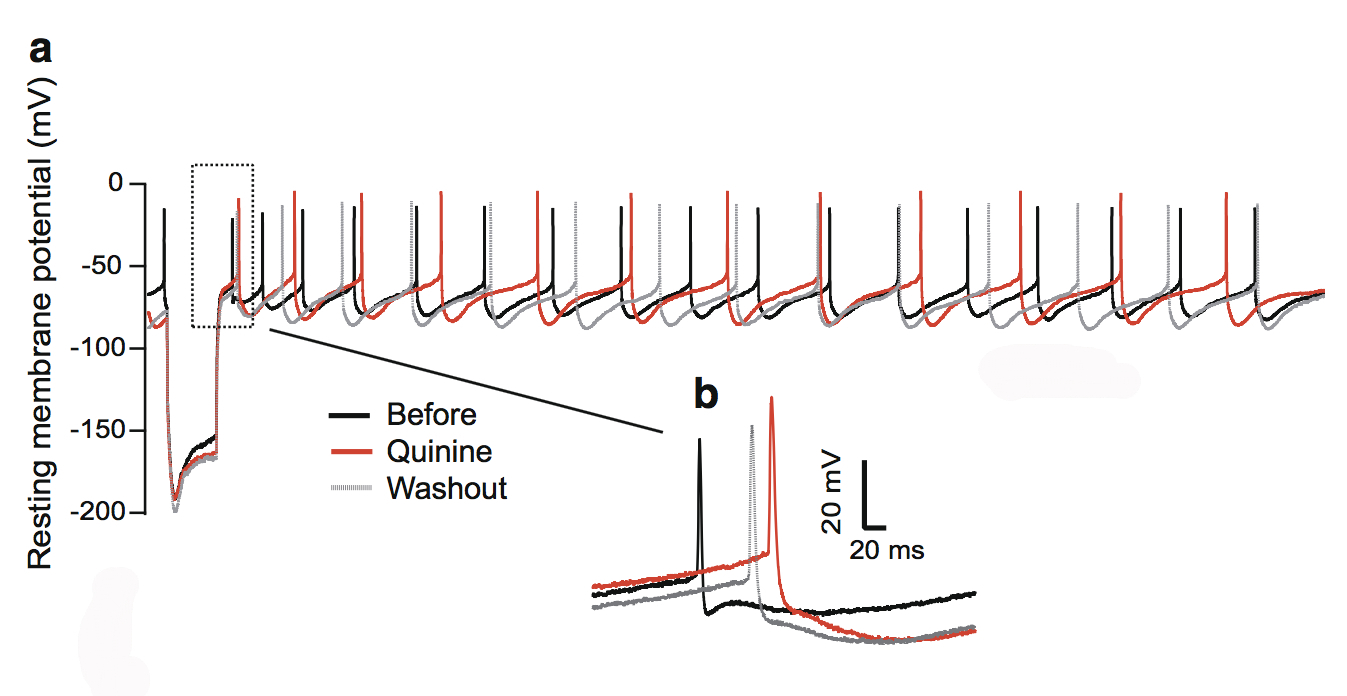

This figure shows the quinine effect on the physiology of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, a structure in the midbrain.

During this phantom ringing/buzzing sensation, neurons in the auditory cortex continue to fire in the absence of a sound source, or even after deafferentation following the loss of auditory hair cells. The underlying mechanisms of tinnitus are not yet known.

In our paper published in the journal Neurotoxicity Research in July 2018, my team and I examined chemical-induced tinnitus as a side effect of medication. Tinnitus patients who have chemical-induced tinnitus comprise a significant portion of all tinnitus sufferers, and approaching this type of tinnitus can help us to understand tinnitus in general.

We focused on quinine, an antimalarial drug that also causes hearing loss and tinnitus. We theorized this is due to the disruption of dopamine neurons rather than cochlear hair cells through the blockade of neuronal ion channels in the auditory system. We found that dopamine neurons are more sensitive than the hair cells or ganglion neurons in the auditory system. To a lesser extent, quinine also causes muscle reactions such as tremors and spasms (dystonia) and the loss of control over body movements (ataxia).

As dopaminergic neurons (nerve cells that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine) are implicated in playing a role in all of these diseases, we tested the toxicity of quinine on induced dopaminergic neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells and isolated dopaminergic neurons from the mouse brain.

We found that quinine can affect the basic physiological function of dopamine neurons in humans and mice. Specifically, we found it can target and disturb the hyperpolarization-dependent ion channels in dopamine neurons. This toxicity of quinine may underlie the movement disorders and depression seen in quinine overdoses (cinchonism), and understanding this mechanism will help to learn how dopamine plays a role in tinnitus modulation.

A 2015 ERG scientist, Xiping Zhan, Ph.D., received the Les Paul Foundation Award for Tinnitus Research. He is an assistant professor of physiology and biophysics at Howard University in Washington, D.C. One figure from the paper appeared on the cover of the July 2018 issue of Neurotoxicity Research.

We need your help supporting innovative hearing and balance science through our Emerging Research Grants program. Please make a contribution today.

How My Hearing Loss Makes Me Better at My Job

By Sarah Bricker

My hearing loss journey led me to a position as a communications specialist at Starkey Hearing Technologies, the Minnesota-based hearing aids manufacturer. Managing a hearing loss at work has meant that I sometimes have trouble hearing speech in noisy conference rooms, and that I may miss various sound cues during international phone calls. Yet as I navigate these challenges in the office, I can also see that having a hearing loss has actually helped me to become a better employee.

I am comfortable asking for help. There’s a misconception that asking for help means you’re incapable of doing your job or it will make your boss or colleagues think less of you. But I see asking for assistance as showing an interest in learning and growth and a desire to recognize weaknesses and overcome them.

“Hard work” is my middle name. Having a disability often means I have to work a little harder than those with full abilities. I may have to try harder to hear in staff meetings, when talking to clients on the phone, or when attending a seminar in a large auditorium—but I also focus and do due diligence before and after meetings and calls to make sure I didn’t miss anything. Even with my hearing aids, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

I find creative solutions. Because my hearing loss can sometimes prevent me from doing something the usual way, I am always looking for an innovative approach. I believe this is a life skill that will enable me to take on challenging projects at the office and figure out solutions others may not have considered.

I am more accurate in my work. I know I may miss parts of conversations and other sound signals, but being aware of this has set me up to be extremely detail-oriented otherwise. I am hyper-aware of all the minutiae and will carefully analyze each element of an assignment before I consider a project finished.

I work well alone and with a team! Having a hearing loss means I’ve learned the skills necessary to be self- sufficient and to succeed on my own. By the same token, my hearing loss has also given me an underlying “Go Team!” attitude from years of asking for help. I know I can rely on my team, whether it’s to fully follow a group discussion or to make sure I get all the notes I need in a conference hall.

I am patient. Hearing loss means I may have to listen to the same phrase three times before understanding it, but that’s okay. I’ve learned that getting it right is more important than getting it right now. That outlook is extremely beneficial when it comes to long-term projects and client relationships, not to mention everyday interactions with colleagues, friends, and family.

Texas native Sarah Bricker holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri and is a communications specialist at Starkey Hearing Technologies in Minnesota. She has a profound progressive sensorineural hearing loss that was diagnosed at age 13. This article originally appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Hearing Health magazine.