I was about 9 when hearing loss in my left ear was first detected. The audiologist explained to me that as a result, I may not be able to hear birds singing as easily, and that I may need to concentrate more to understand words starting with “sh,” “k,” or “t.” Sensing my alarm, she tried to reassure me by saying it was unlikely that the hearing loss would affect both ears, and if it did, it would likely not be to the same extent.

Managing the loss of a primary sense is all about adaptation. In grade school, I simply tilted my right ear toward sound sources. Over time my hearing loss became bilateral and progressive, and its cause remains unknown. In graduate school I began using hearing aids and later received a cochlear implant in my left ear. I continue to use a hearing aid in my right ear, and thankfully for the past eight years, my hearing has remained stable, if stably poor.

I have always compensated. At Boston College (where I received my undergraduate, Master’s, and Ph.D., all in the biological sciences) I sat in the front seat of my classes, as close to the speaker as possible. I asked my professors and classmates to face me when they spoke so I could use visual cues to enhance oral comprehension. During postdoctoral training in auditory neuroscience at Purdue University, I was given complimentary assistive listening technology upon my arrival to the lab.

While I do not consider my hearing loss to be a profound limitation personally or professionally, it has certainly sculpted my career path. When picking my area of scientific focus, I settled on a career in auditory neuroscience to better understand hearing loss.

I also reasoned that the auditory research conferences and meetings I’d be attending would likely have assistive listening technology to allow me to participate more fully. I have benefited immeasurably from the scientific community that makes up the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, whose meetings have world-class assistive listening technologies and interpreter services plus overwhelming support of members who have hearing loss.

As I entered my 40s, I experienced vertigo for the first time. The clinical data do not fit with a diagnosis of Ménière’s disease, and the link between my vertigo and hearing loss is unclear.

When I have an acute attack of dizziness, my visual field scrolls from right to left very quickly so that I must close my eyes to avoid profound motion sickness and vomiting. I must lie down until the dizziness subsides, which is usually 12 to 16 hours. I honestly cannot do anything—I can only hope to fall asleep quickly.

Vertigo is a profound limitation for me. With no disrespect or insensitivity intended toward the hearing impaired community—of which I am a passionate member—I would take hearing loss over vertigo in a heartbeat. Dizziness incapacitates me, and I cannot be an effective researcher, educator, husband, or father. Some people perceive an aura before their dizziness occurs, but I do not get any advance warning. Unlike hearing loss, I cannot manage my dizziness—it takes hold and lets go when it wants to.

I recall one episode especially vividly. I was invited to give a seminar at the National Institute on Deafness and Other Disorders (NIDCD) and experienced a severe attack just hours before my flight. Vertigo forced me to reschedule my visit, which was tremendously frustrating. That night, I slept in the bathroom (my best solution when vertigo hits). Vestibular (balance) dysfunction is quite simply a game changer.

A satisfying part of my research involves trying to define treatments for hearing loss and dizziness. Usher syndrome is a condition combining hearing, balance, and vision disorders. In Usher syndrome type 1, infants are born deaf and have severe vestibular problems; vision abnormalities appear by around age 10. In working with a group of dedicated colleagues at various institutions, we have evidence that fetal administration of a drug in mice with Usher syndrome type 1 can prevent balance abnormalities.

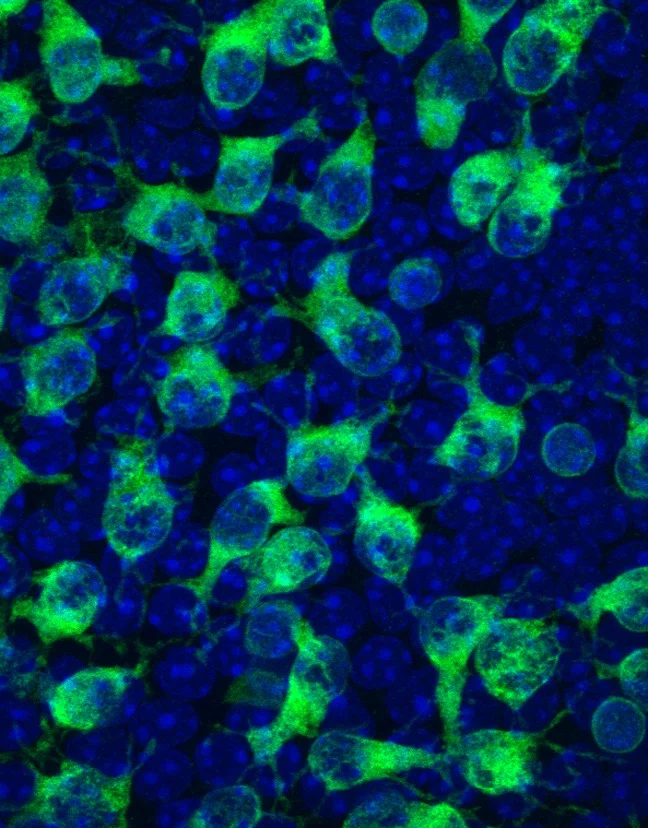

As part of HHF’s Hearing Restoration Project (HRP) consortium, I have been working on testing gene candidates in mice for their ability to trigger hair cell regeneration. This research is exciting as it is leading the HRP into phase 2 of its strategic plan, with phase 3 involving further testing for drug therapies. The probability is that manipulating a single gene will not provide lasting hearing restoration, and that we will need to figure out how to manipulate multiple genes in concert to achieve the best therapeutic outcomes.

It is an exciting time to be a neuroscientist interested in trying to find ways to help patients with hearing loss and balance issues. I am hopeful that we will make progress in defining new ways to treat and even prevent vertigo in the near future and ultimately to discover a cure for hearing loss and tinnitus.