(Desplácese hacia abajo para ver la traducción al español).

At age 9 I could have no idea that the sound sensitivity my mom’s new husband had would also affect me, and more severely, before I even graduated from high school—hyperacusis.

By Jerad J.D. Rider

“Rare” is often the word that speculators write in forums, support groups, and even medical circles regarding hyperacusis’s prevalence, a cruel condition where the sounds of daily life are felt as loud or painful—or both, in many cases.

These different types of hyperacusis warp acoustic worlds: loudness hyperacusis, where the world is acoustically cranked, as if the volume is stuck at a deafening level; and pain hyperacusis (noxacusis), causing burning, stabbing, aching, and/or radiating cramps, triggered by certain sounds or almost every sound and sinking their claws into the close surroundings of the ears, such as the cheeks and jaw areas.

When coming across these conditions, they undoubtedly feel rare, like finding a needle in a haystack. But if they’re rare, how rare? No one really knows, and scientific data needs to answer that.

Jerad with his older brother and mom, around the time Ken (below) became his stepfather, and inadvertently introduced him to sound intolerance conditions, which Jerad now lives with.

If you have hyperacusis, though, a random, chance encounter of meeting another with it too is likely rather slim. Not impossible, but most improbable, as even ENTs will often reveal that they’d never met a hyperacusis patient in the course of their careers lasting several decades.

And they should have the highest probability of meeting such a person. That shows you how rare that hyperacusis must be.

With that in mind, I have a story to share with you that’s really quite remarkable, and it’s about my own chance encounter when I was just a kid: I randomly met someone with pain and loudness hyperacusis, and not just any person—he was my stepdad at the time, a big part of my childhood.

This was long before I myself experienced these ear conditions. In 1994, when Ken became part of our lives, I was only 9, and later would acquire loudness hyperacusis and pain hyperacusis in my sophomore year of high school, when I was 17 years old.

Nowadays they’re so severe I haven’t left my house in over three years—because when I do, these two hyperacusis conditions permanently worsen, even when using ear protection such as earplugs and earmuffs. The burning and stabbing sensations from riding in a car, nature’s assortment of singing birds, and even simple conversations are just a few examples of my crippling condition.

Simply rubbing my head sounds too loud to me, causing pain. It also causes my tinnitus to spike (which yes, I have too—hyperacusis and tinnitus often occur together). These conditions cripple life because the sounds of life are everywhere and independent of what you yourself do. Everything in life is tied to sound, isn’t it?

But I think it is uncanny how by sheer happenstance, I had randomly encountered a person with these same conditions, a 40-something construction worker who over the course of several months wooed my mother while dining at Shoney’s, her waitressing job in Columbus, Ohio. They started to date and eventually married.

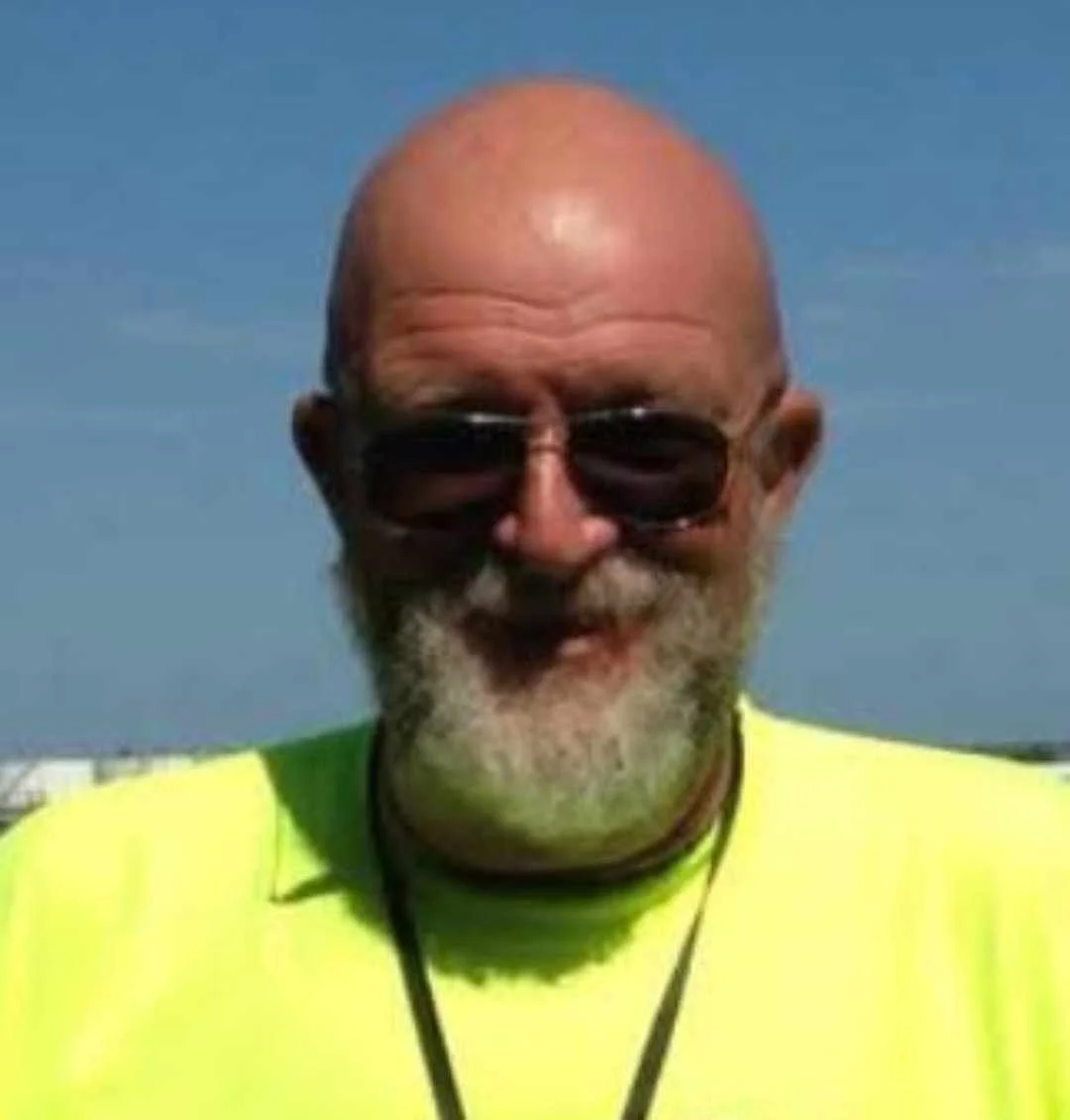

Ken was a tall and bulky charmer with a bald head and goatee, and he was very forthright. After the marriage he confided to my mom that he had developed a mild to moderate sound intolerance from frequent loud exposures in his construction job, from bulldozers, claw hammers, jackhammers, etc.

My brother Daniel and I learned of Ken’s aversion to sounds not long after we moved into his house. One day we were filming with our VHS camcorder upstairs, lightly running on the floor, and that created a racket.

Ken quietly came up the stairs and with a face of fierce disgust subdued by calm control to block a noise showdown, he spoke softly: “Please don’t run up here. It makes a lot of noise.”

So then we tried our very best to honor his request, yet as the months unfolded, Daniel and I discovered that it didn’t take a lot to cause noise, and Ken became more vocal, angrier with every plea. Understandable to me now.

Our mom also told us to keep the noise down, and relayed the information the best she could. Ken didn’t call it hyperacusis. Before the Internet, most were unaware that “hyperacusis” was the term for his condition, and “noxacusis” hadn’t been coined yet.

Jerad, his mom, and brother in a recent photo.

Ken just described it as a “sensitivity to certain noise frequencies with pain inside the ears and some things sounding louder.”

After four years of marriage, Ken and Mom divorced, not because of the hyperacusis—it was other things. But four years after that, I myself experienced mild pain and loudness hyperacusis (also mild tinnitus) after an ototoxic reaction from an acne medication. My conditions grew to a severe level in 2022.

Now I could understand Ken, thinking, Ahh, so that was why he always spoke so softly, since raising his voice would've triggered pain.

That was why Mandy and Bo—his two golden retrievers—irked him when they barked their heads off every day.

That was why Ken was never loud, never slapping mugs on a counter or clanking silverware. That was why the thumping racket of "footbeats" hitting carpet or hardwood tortured him.

Yes, indeed. This all made total sense.

Looking back, I often wonder if my meeting Ken was more than chance, like an omen for a little boy, a godhead’s proclamation: Hey, there’s a storm coming, something big, and if you don’t acknowledge it, you’ll wind up like Kenneth, boy. Maybe that was accurate, or maybe it was nothing more than just a chance encounter.

The good news is that Ken's life went on happily. He remarried, enjoyed retirement, and didn't pass until 2020, from cancer. He was 68. He never knew that I developed these conditions, too, over 20 years ago. We didn't stay in touch, but after his death I learned his life had been fulfilling by reading his obituary online.

I was glad his ear conditions didn't worsen to the point of swallowing his precious life and ending it a tragedy. He ended on a high note, and that’s what he deserved.

Jerad J.D. Rider is the president of Hyperacusis Central, which raises awareness of hyperacusis and co-occurring ear conditions. He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Un Encuentro Fortuito

A los 9 años no pude tener idea de que la sensibilidad al sonido que tenía el nuevo esposo de mi madre también me afectaría, y más severamente, incluso antes de graduarme de la escuela secundaria-la hiperacusia.

Por Jerad J.D. Rider

"Raro" es a menudo la palabra que los especuladores escriben en foros, grupos de apoyo e incluso círculos médicos, con respecto a la prevalencia de la hiperacusia, una condición cruel en la que los sonidos de la vida diaria se sienten como fuertes o dolorosos-o ambos, en muchos casos.

Jerad con su hermano mayor y su madre, en la época en que Ken (abajo) se convirtió en su padrastro, e inadvertidamente lo introdujo a las condiciones de intolerancia sonora, con las que Jerad ahora vive.

Estos diferentes tipos de hiperacusia deforman los mundos acústicos: la hiperacusia del sonido fuerte, en la que el mundo está acústicamente alterado, como si el volumen estuviera atascado en un nivel ensordecedor; y la hiperacusia con dolor o dolorosa (noxacusia), que causa ardor, punzadas, dolor y/o calambres irradiados, desencadenados por ciertos sonidos o casi todos los sonidos, y hundiendo sus garras en las zonas cercanas a las orejas, como las áreas de las mejillas y la mandíbula.

Al encontrarse con estas condiciones, sin duda ellos lo sienten raro, como encontrar una aguja en un pajar. Pero si son raros, ¿qué tan raros? Nadie lo sabe realmente, y los datos científicos necesitan responder a eso.

Sin embargo, si Ud. tiene hiperacusia, la posibilidad de un encuentro aleatorio y casual con otra persona que también la tenga, es bastante escasa. No es imposible, pero sí lo más improbable, ya que incluso los otorrinolaringólogos a menudo revelan que nunca han conocido a un paciente con hiperacusia en el transcurso de sus carreras que duran varias décadas.

Y ellos deberían tener la mayor probabilidad de conocer a una persona así. Eso le demuestra lo rara que debe ser la hiperacusia.

Con eso en mente, tengo una historia para compartir con ustedes que es realmente bastante notable, y se trata de mi propio encuentro casual cuando era solo un niño: conocí al azar a alguien con hiperacusia dolorosa e hiperacusia del sonido fuerte, y no cualquier persona-era mi padrastro en ese momento, una gran parte de mi infancia.

Esto fue mucho antes de que yo mismo experimentara estas afecciones auditivas. En 1994, cuando Ken se convirtió en parte de nuestras vidas, yo tenía solo 9 años, y más tarde adquiriría hiperacusia del sonido fuerte e hiperacusia con dolor, en mi segundo año de escuela secundaria, cuando tenía 17 años.

Hoy en día están tan severas que no he salido de mi casa en más de tres años-porque cuando lo hago, estas dos condiciones de hiperacusia empeoran permanentemente, incluso usando protección auditiva como tapones para los oídos y orejeras. Las sensaciones de ardor y punzadas al viajar en un automóvil, la variedad de pájaros cantores de la naturaleza e incluso las simples conversaciones, son solo algunos ejemplos de mi condición incapacitante.

El simple hecho de frotarme la cabeza suena demasiado fuerte para mí, causándome dolor. También hace que mi tinnitus se dispare (lo cual sí, yo también tengo-la hiperacusia y el tinnitus a menudo ocurren juntos). Estas condiciones paralizan la existencia porque los sonidos de la vida están en todas partes e independientes de lo que Ud. mismo haga. Todo en la vida está ligado al sonido, ¿no?

Pero creo que es asombroso cómo, por pura casualidad, me encontré al azar con una persona con estas mismas condiciones, un trabajador de la construcción de cuarenta y tantos años que en el transcurso de varios meses cortejó a mi madre mientras cenaba en Shoney's, su trabajo de camarera en Columbus, Ohio. Comenzaron a salir y finalmente se casaron.

Jerad, su madre y su hermano en una foto reciente.

Ken era un hombre encantador, alto y corpulento, con la cabeza calva y barba de chivo, y era muy franco. Después del matrimonio, le confió a mi madre que había desarrollado una intolerancia al sonido de leve a moderada debido a las exposiciones frecuentes y fuertes en su trabajo de construcción, con excavadoras, martillos de garra, martillos neumáticos, etc.

Mi hermano Daniel y yo nos enteramos de la aversión de Ken a los sonidos poco después de mudarnos a su casa. Un día estábamos filmando con nuestra videocámara VHS en el piso de arriba, corriendo ligeramente por el suelo, y eso creó un alboroto.

Ken subió silenciosamente las escaleras y, con una expresión de feroz disgusto contenida por un control de la calma para evitar un altercado debido al ruido, habló en voz baja: "Por favor, no corras aquí. Hace mucho ruido".

Así que hicimos todo lo posible para cumplir con su pedido, pero a medida que pasaban los meses, Daniel y yo descubrimos que no se necesitaba mucho para causar ruido, y Ken se volvió más expresivo, más enojado con cada súplica. Ahora es comprensible para mí.

Nuestra mamá también nos dijo que mantuviéramos el ruido bajo y transmitió la información lo mejor que pudo. Ken no lo llamaba hiperacusia. Antes de Internet, la mayoría desconocía que "hiperacusia" era el término para su condición, y la "noxacusia" aún no se había acuñado.

Ken simplemente lo describía como una "sensibilidad a ciertas frecuencias de ruido, con dolor dentro de los oídos, y con algunas cosas sonando más fuerte".

Después de cuatro años de matrimonio, Ken y mamá se divorciaron, no por la hiperacusia-sino por otras cosas. Pero cuatro años después de eso, yo mismo experimenté una hiperacusia con dolor e hiperacusia de sonido fuerte leves (también tinnitus leve), después de una reacción ototóxica a un medicamento para el acné. Mis condiciones crecieron a un nivel severo en el 2022.

Ahora podía entender a Ken, pensando, Ahh, por eso siempre hablaba tan bajo, ya que levantar la voz le habría desencadenado dolor.

Esa era la razón por la que Mandy y Bo-sus dos golden retrievers-, lo irritaban cuando ladraban a todo pulmón todos los días.

Esa era la razón por la que Ken nunca era ruidoso, nunca golpeaba tazas en un mostrador o repiqueteaba cubiertos. Por eso le torturaba el estruendo de los "pasos" al golpear la alfombra o la madera dura.

Sí, efectivamente. Todo esto tenía mucho sentido.

Mirando hacia atrás, a menudo me pregunto si mi encuentro con Ken fue más que una casualidad, como un presagio para un niño pequeño, una declaración divina: Oye, se avecina una tormenta, algo grande, y si no lo reconoces, terminarás como Kenneth, muchacho. Tal vez eso fue así, o tal vez no fue más que solo un encuentro casual.

La buena noticia es que la vida de Ken continuó de manera feliz. Se volvió a casar, disfrutó de la jubilación y no falleció hasta el 2020, de cáncer. Tenía 68 años. El nunca supo que yo también desarrollé estas condiciones, hace más de 20 años. No nos mantuvimos en contacto, pero después de su muerte supe que su vida había sido satisfactoria al leer su obituario en línea.

Me alegré de que las condiciones de sus oídos no empeoraran hasta el punto de tragarse su preciosa vida, terminando como una tragedia. Acabó con una nota alta, y eso es lo que él se merecía.

Jerad J.D. Rider es el presidente de Hyperacusis Central, que crea conciencia sobre la hiperacusia y las afecciones del oído coexistentes. Vive en Columbus, Ohio.

Traducción al español realizada por Julio Flores-Alberca, abril 2025. Sepa más aquí.

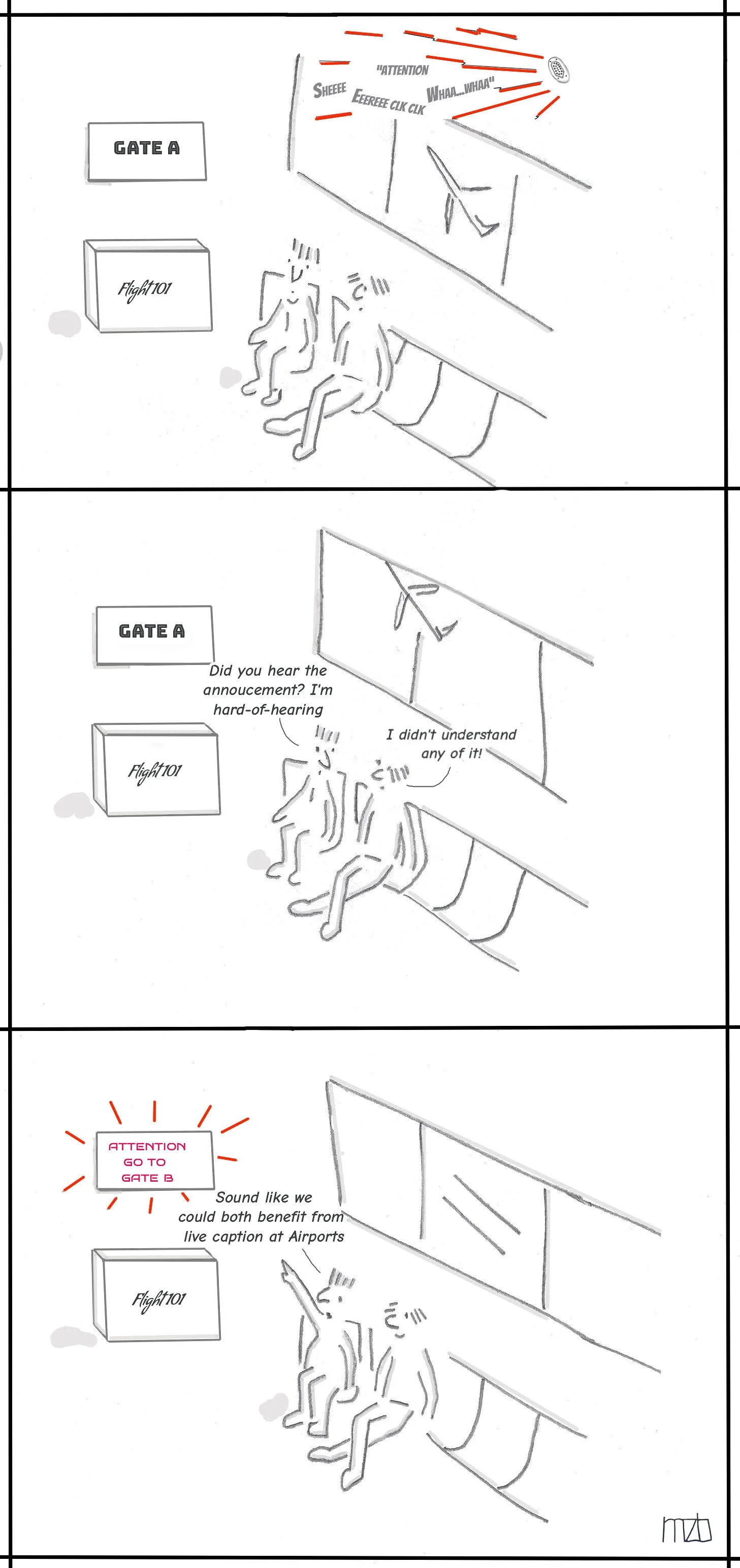

For individuals with long-term hearing loss or severely degraded auditory input, the lack of reliable auditory feedback represents a challenge many orders of magnitude greater than the temporary masking used in this study.