By Tara Guastella

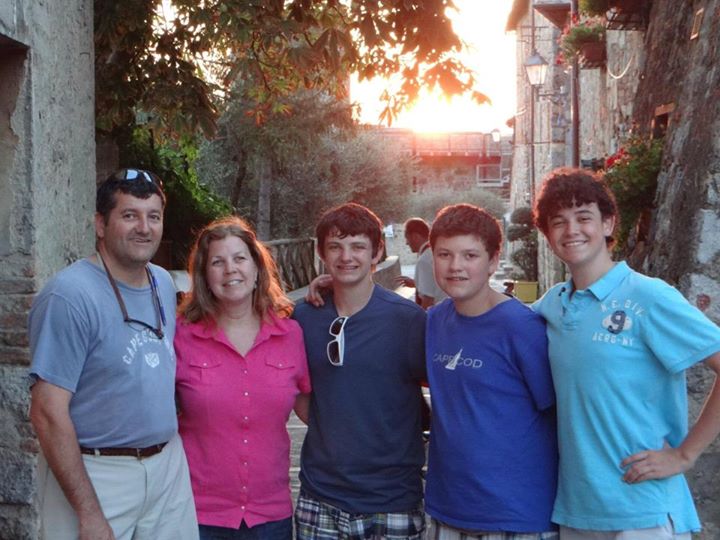

Shannon Silvestri and her two teenage children attended the 2013 Boston Marathon to cheer on dad Kevin. It was the third time they’d be watching him run the marathon.

The family was invited to watch the race by Ashworth Awards, the company that creates the marathon medals and which is based in the same town where the family lives. They were at the Lenox Hotel, located at Exeter and Boylston streets in Boston. After Kevin ran by (finishing what would be his personal best race time), and Shannon received an automated text message that he had finished the race, they gathered their things, snapped a few photos, and began exiting out a side door of the Lenox on Exeter Street. Shannon was walking between her son in front of her, her daughter with a friend behind her, and two of her husband’s friends behind them.

As they were passing through the barricades set up to keep the thousands of spectators organized, the first explosion occurred. It was the first of two homemade pressure cooker bombs that exploded that day. The blast occurred to the left side of Shannon and her family, but the sound bounced off the building and hit Shannon in her right ear. “I could feel the air and the sound waves hit me,” she says. “I could really feel it.”

She immediately covered her ears, fell to the ground, and then looked front and back to check on her children. "Everything seemed like it was in slow motion," she says. Her daughter immediately let out a big scream, knowing her father was out there. Her son ran and Shannon finally found him a couple of streets away. Shannon says, "This was his fight-or-flight response."

Seconds later, the second blast occurred and again it hit Shannon in her right ear as she was turned to comfort her daughter. “It was such a strong feeling of pressure, or a blockage, in both my ears. It felt like I really needed to pop them,” she says. “All I could hear was a muffled chaotic mess and when I looked back all I saw was smoke, debris, and metal barricades flying through the air as people were trying to escape the horror that just occurred.”

Shannon thought terrorists were attacking the city by plane. Her cousin’s husband was killed in the 9/11 attacks so this was the first thing that came to mind. Needing to find Kevin, they headed toward the family meeting area even though law enforcement was trying to keep people from entering this area. Shannon remembers thinking, “I don’t care how many pieces he is in, I am taking him home.” She felt selfish, hurt, empty, alone, and every other emotion she could think of. She didn’t care what scenario she was bringing her kids into, she had to bring the four of them home together.

What the family didn’t realize at the time was that they were closer to the blasts than Kevin was. At the time of the explosions, Kevin was farther down the road, past the finish line, picking up his finisher medal.

Since cell phone service wasn’t working properly, one of Kevin’s friends who was with the family ran ahead to find him. "He was like my superman, whipping off his jacket and saying, ‘I will find him,’” Shannon says. Suddenly, she saw Kevin emerge with the friend. Kevin was uninjured.

Shannon hugged him and remembers saying, “These are the times I appreciate your stubbornness.” Kevin had earlier said he wanted to beat his first marathon time.

Next the family attempted to get out of Boston but everything was on lockdown, including Shannon’s car. They decided to walk the nearly three miles to the Boston Athletic Club. Her son was very upset that Shannon had scraped her knee and wanted to get her something for it. The family stayed there for almost four hours. It was very emotional with people hugging, crying, and reuniting with family and friends.

Shannon went into a restroom because she felt like she needed a good cry but didn’t want to do so in front of her kids. Inside, she met a young teenage girl who worked at the club. The girl couldn’t get in touch with her mother and was frightened by the stories she was hearing. “I told her that I’m a mother and asked if she wanted a hug,” Shannon says. The girl hugged her tightly and the two cried together for a few minutes and then felt better.

Later that week after the bombings, Shannon’s left ear “popped” as did her son’s ears. As for Shannon's right ear, that never popped. Luckily, her daughter’s ears were unaffected.

To help survivors cope with the events of last year’s bombing, Shannon started a website called Boston Strong: Strength, Courage, & Healing and she began making Boston Strong pins/charms. All of the proceeds go to help survivors.

Over a year later, Shannon’s hearing in her right ear has worsened, as has her tinnitus, and her left ear also has a degree of hearing loss. Certain noises and sensations cause pain, a condition known as hyperacusis, so she decided not to get hearing aids. Her audiologist told her that at some point she may lose most if not all hearing in her right ear.

Recently, Shannon accepted a position at the Massachusetts Office of Victim Assistance, which has been instrumental in helping marathon survivors. She will be leading a peer-to-peer support network for people who sustained hearing loss as a result of the blasts. Shannon says she wants to help others cope. “People don’t recognize hearing loss as something that is life-changing. It’s a non-healing injury,” she says.