A new paper in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, “It’s Time to Change Our Message About Hearing Loss and Dementia,” argues that linking hearing loss and dementia helps create the assumption that hearing loss necessarily leads to dementia. This, the authors say, has the potential to stigmatize people with hearing loss who already may be experiencing bias at the workplace, in social situations, and in other areas.

The paper’s authors—Jan Blustein, M.D., Ph.D., Barbara E. Weinstein, Ph.D., and Joshua Chodosh, M.D., MSHS—acknowledge that describing hearing loss as a risk factor for dementia is “true under the strict epidemiologic definition of ‘risk’”—but that the lay public’s understanding of the difference between correlation and causation means that using “risk” in messaging “implies a warning about an impending adverse event.”

While the authors note that “several prospective cohort studies have found an association between hearing loss and incident dementia,” the precise mechanism for the link is still uncertain. The paper details four theories: 1) It could be that the social isolation that can come with hearing loss contributes to cognitive decline; 2) the “cognitive load” that comes with trying to understand speech diverts resources for other brain tasks; 3) some unknown factor tied to aging affects hearing as well as the brain; and 4) hearing loss could trigger degenerative changes in the brain such as atrophy.

A societal stigma against people with hearing loss is real, whether the loss is treated or not, and can include assumptions about being less intelligent or less competent. The paper warns that tying cognition so closely to hearing ability can serve to make this bias more pronounced while also increasing anxiety about dementia among the general public.

We here at Hearing Health Foundation have been careful to note that the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline and dementia is just that—correlation and not causation. We also emphasize that the research shows the association is with untreated hearing loss, that is, not treated with the use of hearing aids or cochlear implants. This supports our message of prevention, especially around noise-induced hearing loss: to not take hearing for granted, to proactively take care of it (avoiding excess noise, using earplugs, turning down the volume, taking listening breaks), to get it tested regularly, and if needed to get it treated.

The authors conclude with a suggestion to resist using the trigger word “dementia” in messaging around healthy hearing:

“Given the complexity and uncertainty of the hearing loss–dementia link, and in view of the potential harms of stigmatization, we favor constructive messages that minimize harm while motivating people to act. One such message might be: ‘Hearing better can help you think better.’ We would omit mention of dementia when addressing the hearing challenges faced by millions of older Americans.”

We love this framing and will promote it! —Yishane Lee

PS: The paper also addresses a question we’ve received regarding any association between dementia and those born with hearing loss, with an answer that makes sense and is not surprising:

"Hearing loss as discussed here generally refers to age-related hearing loss. A clear message would exclude those who identify as deaf (yes, with a capital ‘D’). This group uses sign language to communicate and does not rely on their hearing. They would not benefit from better hearing. To our knowledge, there is no evidence that the risk of dementia in this population is any different than the general public."

Thanks to Abram Bailey, Au.D., at HearingTracker.com for bringing attention to this paper.

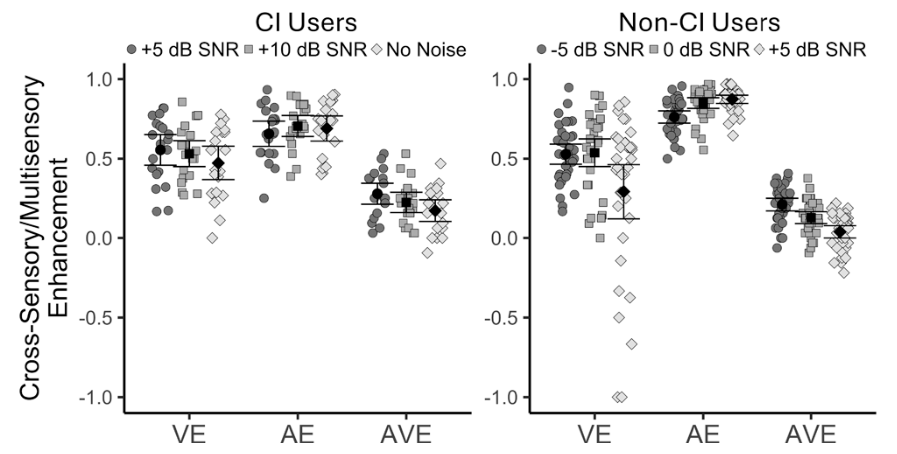

For individuals with long-term hearing loss or severely degraded auditory input, the lack of reliable auditory feedback represents a challenge many orders of magnitude greater than the temporary masking used in this study.