The two groups ended up on opposite sides of Hereford and Commonwealth Avenue while watching the race. After their friend Diane ran by, both groups started to head to the finish line on Boylston Street. Jean was busy taking photographs of other runners, and like any teenage son, Mitchell urged his mother to hurry up and the two began to bicker. Mitchell was eager to get to the finish line and starting to get impatient. “If we hadn’t been bickering, we would have been closer to the explosions,” says Jean, referring to the two homemade pressure-cooker bombs that exploded that day.

“That blast felt like a hurricane and immediately, it looked like a war zone,” she says. Jean has a sensorineural hearing loss in both ears, she instinctively leaned her “better ear”, the left one toward the first blast. “I knew immediately my hearing loss had worsened,” she says. As a result of the bombings, she also lost discrimination in both of her ears and her tinnitus worsened.

Jean and Mitchell ran for their lives clinging to one another. Jean immediately knew it was a bomb. “ I felt like we were in a movie,” Jean says. To get off the street, they ran into a Crate & Barrel store. “The very competent staff helped us escape through a back door,” she says. “They were incredibly kind and helpful. It was almost as if they were trained for it.” Jean adds that Mitchell remained very calm and collected throughout the day’s events, even after getting hit with a piece of shrapnel and his existing tinnitus growing much worse.

At the moment the blasts were occurring, Christopher and his two older sons happened to be taking a shortcut through the Sheraton Hotel to get to the finish line more quickly. “I couldn’t hear a thing,” Christopher says. “I didn’t even know the bombs had gone off.” Corey and Trevor were worried and frantic wondering where Jean and Micthell were. Since cell phone service was quickly overwhelmed following the explosions, the family could not contact one another. It wasn’t until 10pm that night—back in New Hampshire—that the family was reunited.

As soon as the blasts happened, Jean knew she had to see her audiologist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary as she could not hear out of her right ear. She says she had the fleeting thought of trying to go to the hospital in Boston, but at the time it was unclear whether the entire city was under attack. “I needed to find the rest of my family and get out of there,” she says. Jean has bilateral hearing aids and is in a support group for people injured in the Boston Marathon bombings.

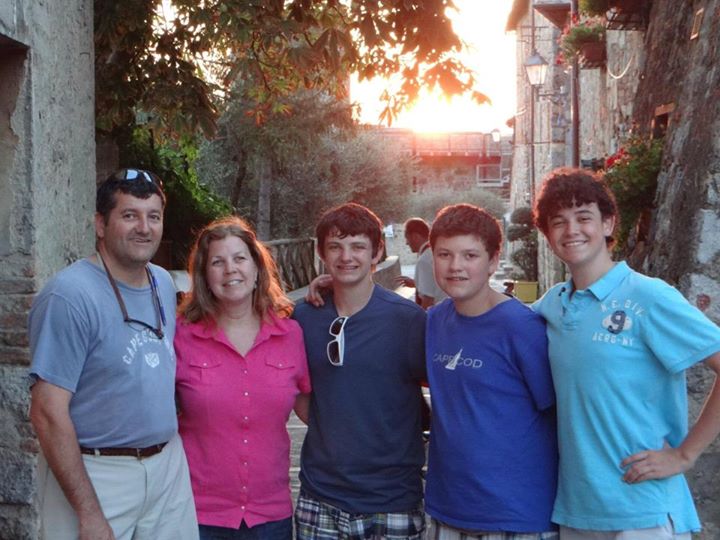

One year later, the Campbell family is running the 2014 Boston Marathon in support of Jean and her recovery. They are fundraising to support Hearing Health Foundation and our search for a cure for hearing loss and tinnitus through the Hearing Restoration Project (HRP). The Campbell family has lived through a traumatic event but since there had been hearing loss in their family, they feel they were slightly better equipped to handle the confusion and depression that can come with sudden hearing loss. “We think educating people about what to expect, and how to cope, is important,” Christopher says.

The Campbells are very encouraged by the strides Hearing Health Foundation and our HRP consortium have made so far toward finding a cure for hearing loss and tinnitus, such as early success with regenerating sensitive inner ear hair cells in adult mice that, in all mammals, once damaged through noise or age lead to permanent hearing loss.

Please join us in supporting the Campbell family as they tackle their first marathon and give hope for a cure within a decade.