By Angela Yarnell Bonino, Ph.D., CCC-A

Young children spend much of their day listening in noise. However, it is clear that, compared with adults, infants and children are highly susceptible to interference from competing background sounds. The ability to listen in competing backgrounds develops slowly over childhood, but the course of development is dependent on the type of background. For example, the developmental trajectory is more pronounced and prolonged for listening for a speech target in a competing speech background than in a steady-state noise background.

Data from infants and school-aged children clearly shows there is substantial improvement in the ability to hear speech embedded in competing backgrounds between these two time points. However, little is known about how the course of development unfolds during the toddler and preschooler years.

Building on our recent methodology improvements for testing young children, the goal of this study was to examine age-related changes for 2- to 15-year-old children in the ability to detect a word presented in one of two competing background sounds: speech (comprising two competing talkers) or a steady-state noise. Children were tested with an observer-based, testing method in which the child is trained to perform a play-based response when the target is heard. Based on the child’s behavior, an experimenter (called an “observer”) determines, of the two possible time intervals, which interval contained the signal.

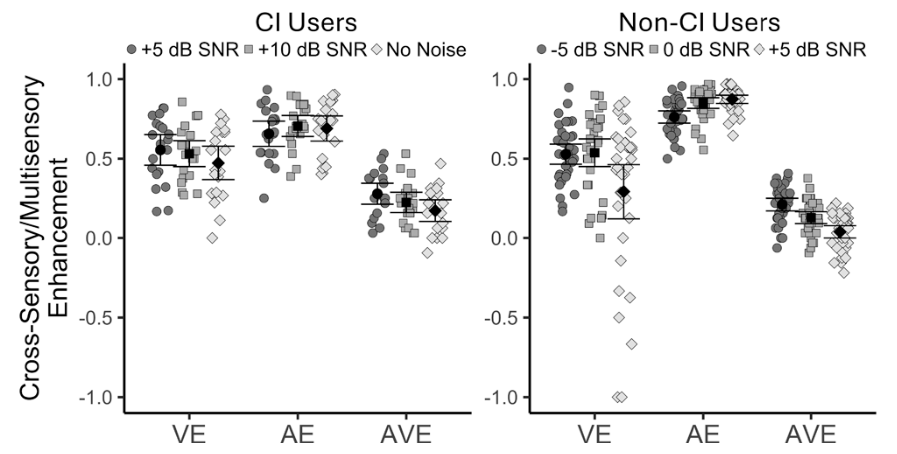

Individual thresholds as a function of child age (in log10 scale). Thresholds in the speech-shaped noise (SSN) condition and the two-talker speech condition are shown in red triangles and blue squares, respectively. The solid line represents the linear function for the child data: red for the noise condition, and blue for the speech condition. For each condition, the dash line shows the 0.05 quantile cutoff based on adult thresholds. Credit: Angela Yarnell Bonino, Ph.D.

Consistent with previous studies, results from our research, published in Ear and Hearing in April 2021, indicate that children had poorer thresholds than adults. Moreover, the child–adult differences were substantially larger for the speech than the noise condition. Based on the 0.05 quantile cutoff from the adult data (the dashed horizontal lines in the figure), adultlike performance was achieved at 6 years of age for the noise condition and at 15 years for the speech condition.

A unique contribution to the literature from our study was that we documented limited improvement in thresholds between 2.5 to 5 years. This finding suggests that the large improvement seen between infants and school-aged children must be the result of auditory development that happens prior to 2.5 years of age. Results from this work also confirm that our testing method can be used to reliably collect behavioral data from toddlers and preschoolers for complex listening tasks.

Now that we have established normative data for this task, future work in our laboratory will measure thresholds for these stimuli with children with developmental disabilities. Albeit limited, previous studies suggest that children with developmental disabilities—specifically children with autism spectrum disorder or Down syndrome—have poorer performance for complex listening tasks than age-matched, neurotypical peers.

Documenting performance across the two background types is expected to advance our theoretical understanding of auditory development as well as pave the way for the creation of new clinical tools for monitoring hearing abilities in children with developmental disabilities.

Angela Yarnell Bonino, Ph.D., CCC-A, is an assistant professor in the department of speech, language, and hearing sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder. Bonino is a 2017 Emerging Research Grants scientist generously funded by the General Grand Chapter Royal Arch Masons International.

The internship last summer provided my first real chance to step into hearing science and learn the experimental side of speech perception under the tutelage of a senior researcher.