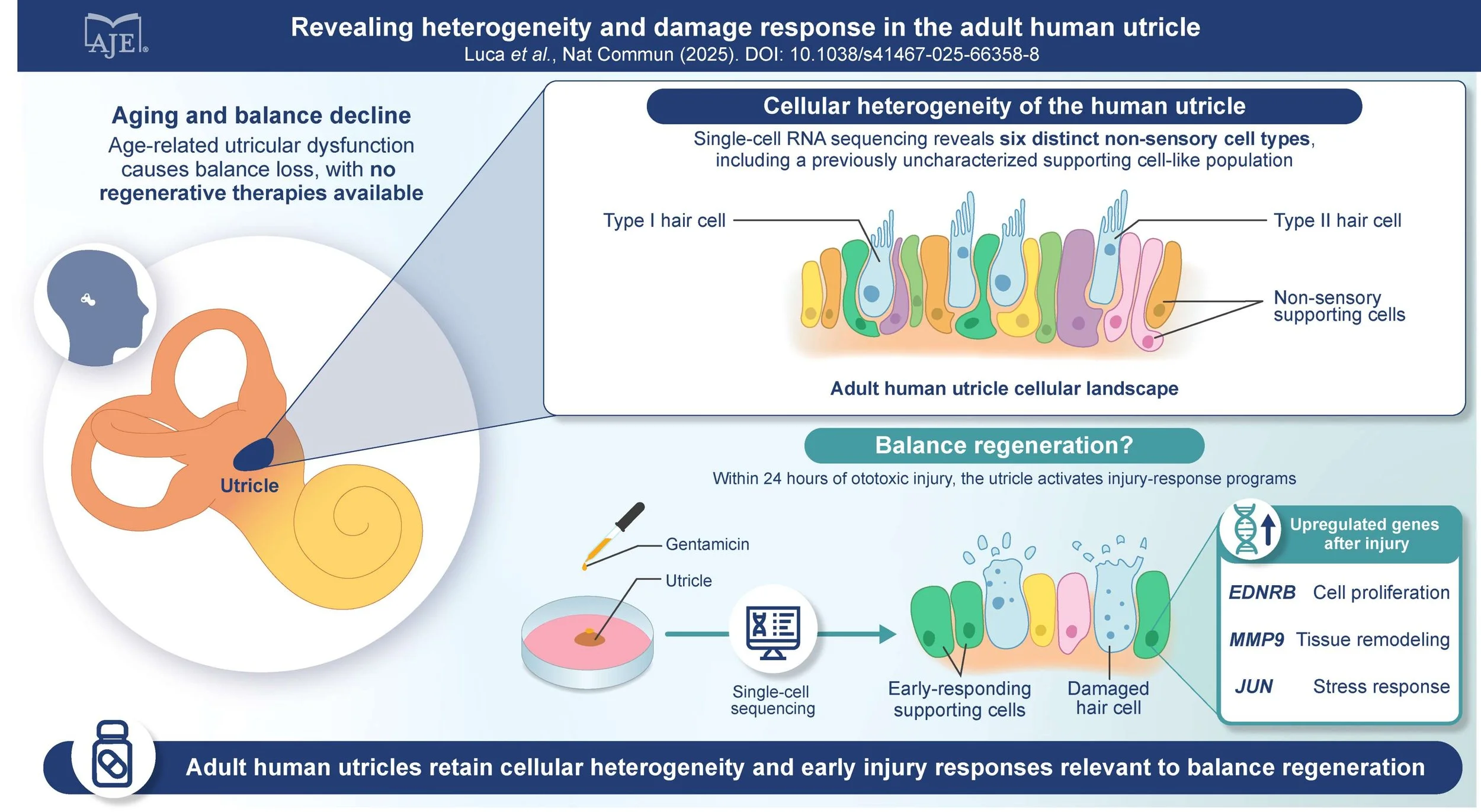

One of the evolutionary disadvantages for mammals, relative to other vertebrates like fish and chickens, is the inability to regenerate sensory hair cells. The inner hair cells in our ears are responsible for transforming sound vibrations and gravitational forces into electrical signals, which we need to detect sound and maintain balance and spatial orientation.

Certain factors, such as exposure to noise or antibiotics, cause inner ear hair cells to die, which leads to hearing loss and vestibular defects, a condition reported by 15 percent of the U.S. adult population. In addition, the ion composition of the fluid surrounding the hair cells needs to be tightly controlled, otherwise hair cell function is compromised, as observed in Ménière’s disease.

While prosthetics like cochlear implants can restore some level of hearing, it may be possible to develop medical therapies to restore hearing through the regeneration of hair cells. Investigator Tatjana Piotrowski, Ph.D., at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Missouri is part of the Hearing Restoration Project of Hearing Health Foundation, which is a consortium of laboratories that do foundational and translational science using fish, chicken, mouse, and cell culture systems.

“To gain a detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms and genes that enable fish to regenerate hair cells, we need to understand which cells give rise to regenerating hair cells and related to that question, how many cell types exist in the sensory organs,” Piotrowski says.

The Piotrowski Lab studies the regeneration of sensory hair cells in the zebrafish lateral line. Located superficially on the fish’s skin, these cells are easy to visualize and to access for experimentation. The sensory organs of the lateral line, known as neuromasts, contain support cells which can readily differentiate into new hair cells.

Confocal microscope image of a Zebrabow fish depicting lateral line neuromasts and ionocytes. CREDIT: Piotrowski Lab

Using techniques to label cells of the same embryonic origin in a particular color, other research had shown that cells within the neuromasts derive from ectodermal thickenings called placodes.

It turns out that while most cells of the zebrafish neuromast do originate from placodes, this isn’t true for all of them.

In a paper published in Developmental Cell online on April 19, 2021, researchers from the Piotrowski Lab describe their discovery of the occasional occurrence of a pair of cells within post-embryonic and adult neuromasts that are not labeled by lateral line markers. When using a technique called Zebrabow to track embryonic cells through development, these cells are labeled a different color than the rest of the neuromast.

Tatjana Piotrowski, Ph.D.. Credit: Jane G. Photography

“I initially thought it was an artifact of the research method,” says Julia Peloggia, a predoctoral researcher at The Graduate School of the Stowers Institute for Medical Research, co-first author of this work along with another predoctoral researcher, Daniela Münch.

“Especially when we are looking just at the nuclei of cells, it’s pretty common in transgenic animal lines that the labels don’t mark all of the cells,” Münch adds.

Peloggia and Münch agreed that it was difficult to discern a pattern at first. “Although these cells have a stereotypical location in the neuromast, they’re not always there. Some neuromasts have them, some don’t, and that threw us off,” Peloggia says.

By applying an experimental method called single-cell RNA sequencing to cells isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, the researchers identified these cells as ionocyte—a specialized type of cell that can regulate the ionic composition of nearby fluid. Using lineage tracing, they determined that the ionocytes derived from skin cells surrounding the neuromast. They named these cells neuromast-associated ionocytes.

Next, they sought to capture the phenomenon using time-lapse and high-resolution live imaging of young larvae.

“In the beginning, we didn’t have a way to trigger invasion by these cells. We were imaging whenever the microscope was available, taking as many time-lapses as possible—over days or weekends—and hoping that we would see the cells invading the neuromasts just by chance,” Münch says.

Ultimately, the researchers observed that the ionocyte progenitor cells migrated into neuromasts as pairs of cells, rearranging between other support cells and hair cells while remaining associated as a pair.

They found that this phenomenon occurred all throughout early larval, later larval, and well into the adult stages in zebrafish. The frequency of neuromast-associated ionocytes correlated with developmental stages, including transfers when larvae were moved from ion-rich embryo medium to ion-poor water.

From each pair, they determined that only one cell was labeled by a Notch pathway reporter tagged with fluorescent red or green protein. To visualize the morphology of both cells, they used serial block face scanning electron microscopy to generate high-resolution, three-dimensional images.

They found that both cells had extensions reaching the apical or top surface of the neuromast, and both often contained thin projections. The Notch-negative cell displayed unique “toothbrush-like” microvilli projecting into the neuromast lumen or interior, reminiscent of that seen in gill and skin ionocytes.

“Once we were able to see the morphology of these cells—how they were really protrusive and interacting with other cells—we realized they might have a complex function in the neuromast,” Münch says.

The Piotrowski Lab studies the regeneration of sensory hair cells in the zebrafish lateral line. Photo Credit: Jane G. Photography.

“Our studies are the first to show that ionocytes invade sensory organs even in adult animals and that they only do so in response to changes in the environment that the animal lives in,” Peloggia says. “These cells therefore likely play an important role allowing the animal to adapt to changing environmental conditions.”

Ionocytes are known to exist in other organ systems. “The inner ear of mammals also contains cells that regulate the ion composition of the fluid that surrounds the hair cells, and dysregulation of this equilibrium leads to hearing and vestibular defects,” Piotrowski says. While ionocyte-like cells exist in other systems, it’s not known whether they exhibit such adaptive and invasive behavior.

“We don’t know if ear ionocytes share the same transcriptome, or collection of gene messages, but they have similar morphology to an extent and may possibly have a similar function, so we think they might be analogous cells,” Münch says.

“Our discovery of neuromast ionocytes will let us test this hypothesis, as well as test how ionocytes modulate hair cell function at the molecular level,” Peloggia says.

Next, the researchers will focus on two related questions—what causes these ionocytes to migrate and invade the neuromast, and what is their specific function?

“Even though we made this astounding observation that ionocytes are highly motile, we still don’t know how the invasion is triggered,” Peloggia says. “Identifying the signals that attract ionocytes and allow them to squeeze into the sensory organs might also teach us how cancer cells invade organs during disease.”

While Peloggia plans to investigate what triggers the cells to differentiate, migrate, and invade, Münch will focus on characterizing the function of the neuromast-associated ionocytes. “The adaptive part is really interesting,” Münch says. “That there is a process involving ionocytes extending into adult stages that could modulate and change the function of an organ—that’s exciting.”

This originally appeared on the Stowers Institute for Medical Research website, at stowers.org/news.

These findings suggest that the ability to integrate what is seen with what is heard becomes increasingly important with age, especially for cochlear implant users.