Hearing Health Foundation’s Hearing Restoration Project (HRP) is the first international research consortium investigating how to regenerate inner ear sensory hair cells in humans to eventually restore hearing. Hair cells detect and turn sound waves into electrical impulses that are sent to the brain for decoding. Once hair cells are damaged or die, hearing is impaired, but in most species, such as birds and fish, hair cells spontaneously regrow and hearing is restored. Following a unique, overarching principle of cross-disciplinary collaboration, nearly instant data sharing, and using multiple animal models, the HRP is working to uncover how to replicate this regeneration process in humans.

HHF welcomed Lisa Goodrich, Ph.D., to the role of HRP scientific Directory in January. Credit: Anna Olivella

Lisa Goodrich, Ph.D., became the new scientific director of the HRP in January 2021, having since 2016 served as a member of HHF’s Scientific Advisory Board. A professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School whose lab focuses on how neural circuits develop and function, Goodrich received a B.A. in biological sciences from Harvard University and her doctorate in neuroscience from Stanford University. After completing postdoctoral training at the University of California, San Francisco (and Stanford, after the lab moved there), she joined the Harvard Medical School faculty in 2002. In mid-March 2021, Goodrich oversaw the annual HRP meeting, leading discussions of outcomes, plans, and structure.

Early Inspiration

When I was in high school, I was fortunate to spend two years with a special biology teacher who helped us to realize that science isn’t just about memorizing facts. She took us out to collect samples from a nearby lake, challenged our assumptions about how the world works, and encouraged us to design and do our own research in school. She even let me set up an aquarium full of breeding medaka in her classroom so I could study them for my project. I remember cutting lunch short so I could peek in and check on my fish. I was so excited when I saw the first eggs! Because of her, I entered college wanting to be a biology major and never looked back.

I have a sister with Down syndrome, so I have always been fascinated by how the brain develops. This was the focus of my graduate research. In my final year of graduate school I went to Seattle to visit my uncle, who introduced me to his friend Ed Rubel. I had lunch with Ed and Jenny Stone, who are past and current HRP members, and learned about the auditory system and hair cell regeneration. It made a big impression.

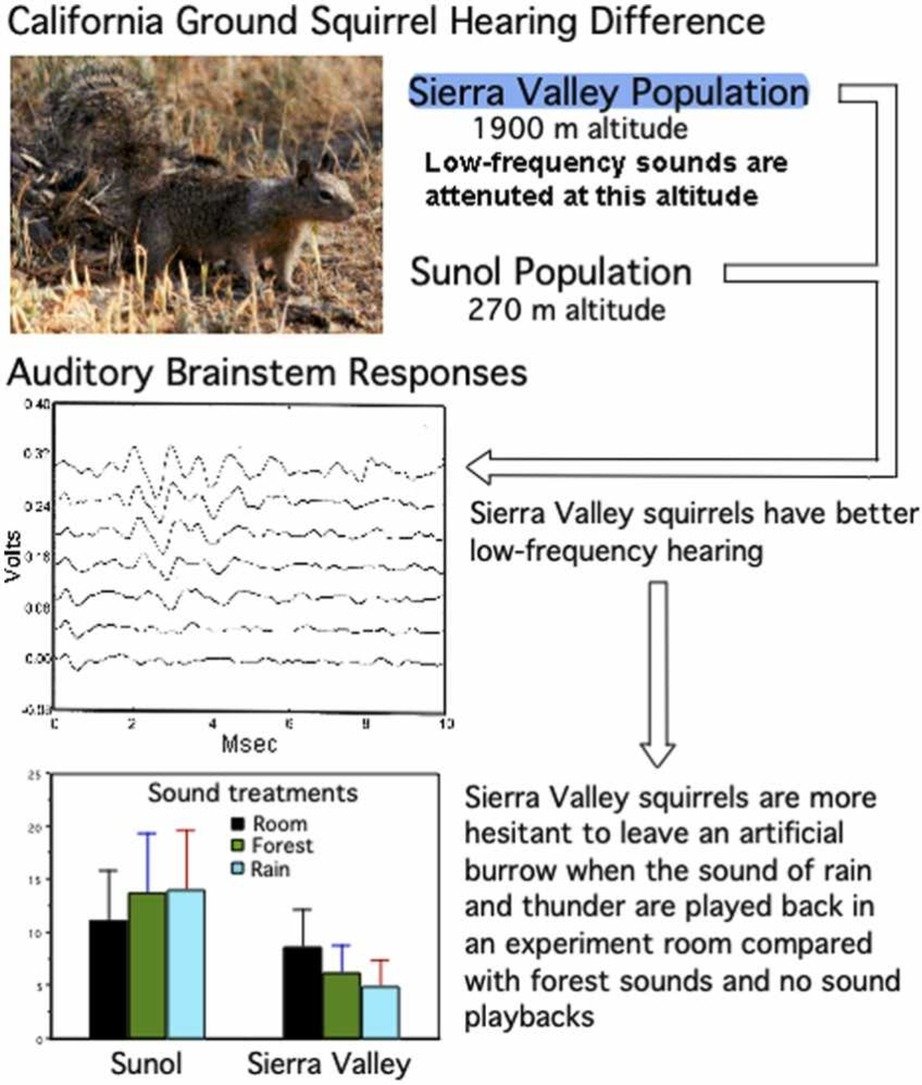

Several years later as a postdoc at UCSF, I reached out to Ed to learn how I might

apply my knowledge of neural development to the auditory system. He invited me up to Seattle to learn some anatomy and also introduced me to folks at UCSF who taught me things like how to dissect the cochlea and record auditory brainstem responses. Around the same time, I got to know HRP member Andy Groves and Scientific Advisory Board member Doris Wu through our shared love for development. Having both trained in

other fields as well, Andy and Doris echoed Ed’s encouragement and gave me the confidence to make the transition to the auditory system. All of these people have been wonderful sources of information, support, and advice ever since, and now as part of the HRP I feel incredibly fortunate to get to work with the people who played such an important role in bringing me into the field.

In the Lab

Our lab studies how neural circuits acquire their specialized, functional properties,

largely in the auditory system. In particular, we are interested in the cellular and

molecular mechanisms that create networks of neurons that reliably encode complex sound stimuli, from the initial detection in the cochlea to the first stage of processing in the auditory brainstem. For instance, we showed that there are multiple molecularly distinct subtypes of spiral ganglion neurons and that this diversification depends on signaling from the hair cell.

We are also fascinated by the stereotyped pattern of connections seen in auditory circuits—synapses are organized by neuron subtype along the base of the hair cell and are organized according to sound frequency along the dendrites of individual target neurons. Several projects are aimed at figuring out how these connections form and what happens to circuit function when they do not.

Although my lab does not study hair cell regeneration, my research benefits from the fantastic tools and resources that the HRP is producing. For example, the gEAR platform created through the HRP makes it possible for anyone to screen hundreds of published datasets, and not just those describing gene expression in the ear. This is one of the wonderful things about the HRP—the impact spreads throughout the field and beyond.

Collaboration

I am most excited by ideas, whether theoretical or practical. I love when I leave a seminar with a new method to try or when I read a paper that suddenly makes me think about our work in a different way. Insights can come from the most random places and without warning, so part of what motivates me every day is knowing that science creates opportunities to do things we never even imagined.

Working with my colleagues in the HRP consortium has exposed me to so many new ways of thinking about hair cell regeneration. I learn something every time we get together—the atmosphere is open, collegial, and inspiring. Rather than having to wait for the papers to be published or try to absorb everything in a 10-minute podium talk, we get to discuss the data as it is unfolding, when it is still possible to incorporate cool new ideas and take advantage of unexpected points of synergy. It is such a great way to do—and appreciate—science.

In the next few years, I hope we will have a molecular language for explaining the phenomenon of regeneration, both when it succeeds and when it fails. HRP consortium members, along with many others in the field, have been collecting and analyzing data from a wide range of systems where hair cells do or do not regenerate. We will learn a lot just by analyzing these data to find patterns within and across systems.

However, our collective experience and intuition as a field will play a huge role in helping us to make sense of what the computers tell us. This is why we want the data and resources to be readily accessible to anyone. It will take many groups working in parallel to find ways to convert supporting cells into hair cells, to hit the perfect balance of proliferation and differentiation, and to functionally integrate these new cells into the cochlea. The good news is we know it is possible because hair cells regenerate naturally in fish and chicks and even in newborn mice. By studying these systems, we can design a blueprint for what needs to happen and then use our rich understanding of the cells and molecules of the mammalian cochlea to make it happen.

Work and Play

These days a typical day for me is pretty simple. I wake up, feed my cats, and then sit in front of the computer typing or talking and often shooing away a cat. I wear many hats, so on any given day I might be recording lectures, grading assignments, talking to someone in my lab about their data, watching a seminar, working on a manuscript, or talking to the folks at Hearing Health Foundation.

I love to escape my brain by being active. Sometimes I squeeze in some yoga or a quick run, but the best days end on the tennis court, weather permitting. I’m not any good but that makes it even more fun. It’s like being a kid again, just delighting in occasionally hitting a ball just right. I am also a devoted reader of fiction, with a peculiar preference for very long books such as Donna Tartt’s “The Goldfinch.” It is very Dickensian, which I love. I think every academic should read “Stoner” by John Williams. It is a gem. And short!

Tinnitus Quest’s Tinnitus Hackathon prioritized active problem-solving, cross-disciplinary debate, and the development of a shared research agenda.