By Stefan Heller, Ph.D.

For over 35 years, we have known that birds naturally regenerate auditory and vestibular hair cells. With support from Hearing Health Foundation’s Hearing Restoration Project, our laboratory has utilized new technology to investigate the mechanisms of this remarkable capability.

A couple of years ago, we started this project and measured the activity of all known genes in individual cells of the chicken’s inner ear. This long-term and systematic research project resulted in a “blueprint” of all known genes in the auditory and vestibular sensory epithelia. (See Cell Reports, March 2021; and Cell Reports, September 2022).

We then continued the work and aimed to categorize genes that change their activity in response to hair cell damage and, ultimately, to hair cell loss. This research identified genes that become activated when hair cells fight for their lives after exposure to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Moreover, it led to the discovery of active signaling pathways in supporting cells when they begin the process of hair cell regeneration. (See Development, April 2022; and Developmental Cell, January 2024).

Our laboratory’s recent work introduced a novel method, infusing the hair cell-toxic aminoglycoside sisomicin directly into the inner ear. Unlike traditional methods such as loud sound exposure or systemic exposure to aminoglycosides, this approach induced profound inner ear damage at an unprecedented speed. It rapidly ablated all hair cells in the chicken’s inner ear, sparking our curiosity about the potential for these severely damaged chickens to fully recover from complete hair cell loss.

Postdoctoral researcher Mitsuo Sato, M.D., Ph.D., and instructor Nesrine Benkafadar, Ph.D., meticulously quantified the new formation of auditory hair cells in chickens after complete hair cell loss. As reported in our team’s latest paper in Cell Reports in March 2024, the timeline of this regeneration process is as follows: New hair cells were observed five days after induced hair cell death, and after three weeks, the full complement of hair cells was restored.

Moreover, the new hair cells started to look mature and established synaptic connections with the chickens’ brains during the second week of recovery. Hearing thresholds, completely absent after aminoglycoside infusion, began to recover during the second week and were wholly restored five weeks after hair cell loss.

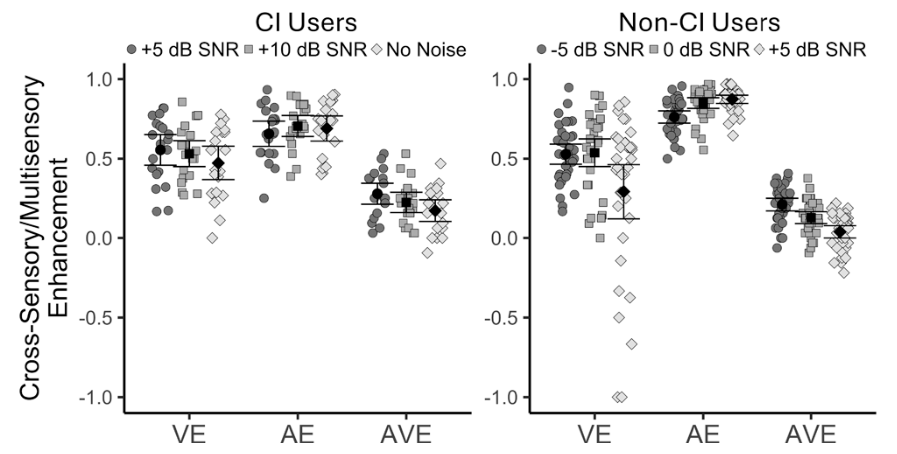

The graph shows an audiogram for chickens before infusing the hair cell toxin into the inner ear (black dots and black line). The image of the chicken hearing organ has hair cells in magenta and supporting cell nuclei in green (control). The red line and data points show complete hearing loss in chickens one day after hair cell toxin infusion (1 d). The destroyed hair cells (magenta) are “floating” above the damaged sensory epithelium. Supporting cells (green) are not dying. Two weeks after this massive damage, hearing thresholds return (green line and triangles), and new hair cells appear in the chicken’s inner ear (14 d). After five weeks (35 d, blue line, and squares), hair cells and hearing thresholds are restored. The graph represents average measurements from six chickens. Some chickens had recovered entirely from hearing loss after 35 days. Credit: Sato et al./Cell Reports

We also discovered that new nerve connections made during regeneration are made differently when compared with the original processes during the development of the inner ear. This suggests that birds maintain a precise program for regeneration that preserves frequency-specific nerve connections, which is an important aspect of proper functional recovery.

I am astounded by the immense regenerative potential of the avian inner ear. This potential, which we now know the bird’s inner ear possesses, is a testament to the groundbreaking works that started with the findings of Ed Rubel, Ph.D., Doug Cotanche, Ph.D., Jeff Corwin, Ph.D., and Brenda Ryals, Ph.D. It is truly a remarkable sight to witness this potential firsthand, a testament to the dedication and perseverance of our research team.

In addition, all the papers cited here were possible because of funding from Hearing Health Foundation, with National Institutes of Health funding only just recently.

Hearing Restoration Project (HRP) member Stefan Heller, Ph.D., is a past Emerging Research Grants scientist, as are Ed Rubel, Ph.D., and Doug Cotanche, Ph.D, whose pioneering research on avian hair cell regeneration helped pave the way for the HRP. Heller is a professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Stanford University, where in his lab Mitsuo Sato, M.D., Ph.D., is a postdoctoral researcher and Nesrine Benkafadar, Ph.D., is an instructor.

It bears repeating: What improves access for a group with a specific disability invariably also helps the greater population.