Most of my life I had no ear problems. I never thought about the noise I was exposed to, certainly never in terms of the grave hazard and enormous threat that I now know it to be.

By David Treworgy

Because of his hyperacusis, David Treworgy has had to sharply curtail activities he used to enjoy, such as running road races.

I grew up in rural Maine and engaged in activities that, along with some kind of underlying susceptibility, probably got me to where I am today. For example, every summer I mowed a lot of lawns—for my family, my grandmother, and my neighbors—using a loud power mower. I also have done a lot of carpentry work with power tools like drills, sanders, and circular saws.

After college, I moved to Washington, D.C., and worked for the federal government as a management consultant. My work was primarily office work, which is relatively quiet. But parts of my job involved a lot of noise. Every day for years I spent two hours on the subway, which routinely reaches injurious noise levels with squealing brakes and train horns. I often flew in loud prop planes to visit government agencies in distant locations, far from major airports.

When I look back, I wish I had worn ear protection. But at the time there was no public health awareness of the dangers of noise.

Odd Ear Symptoms

About 10 years ago, I noticed odd ear symptoms. Working in downtown D.C., where traffic is heavy, I thought the city had raised the volume on its sirens. Before, sirens had never registered with me, just a fixture of city life that I could tune out. But now they were loud enough to cause physical ear pain. It felt like someone stabbing my ear with a knife. I got some earplugs and popped them in whenever an ambulance or fire truck approached, and that managed the problem for several months.

But I soon realized the sirens hadn’t changed—something about my ears had changed. Walking down the sidewalk with a colleague, a shop owner slammed the security shutters to cover the door. The rumble felt like sandpaper rubbing my ears. My colleague didn’t even notice the sound.

Within a month, even more routine sounds began to hurt, especially sudden, high pitched sounds—someone’s cellphone ringing would cause a point of pain deep within the ear canal. One building where I attended meetings had old elevators with a bell that would ding loudly as it passed each floor. Every ding felt like another stab of a knife in my ears.

I discussed my ear problems with my primary care physician, who had no information and referred me to an ENT (ear, nose, and throat doctor, or otolaryngologist). The ENT ordered some standard audiology tests. They all came back normal. The ENT diagnosed me as suffering from severe hyperacusis, but said there was no specific treatment, and suggested I try some supplements, which I did, but they did not help.

I then turned to the internet to research more about hyperacusis, and learned of a treatment called TRT or Tinnitus Retraining Therapy, often touted as having a high success rate for tinnitus and an even higher success rate for hyperacusis. It seemed promising. This treatment involves very mild broadband noise played into the ears via sound generators, with the volume raised very slowly over months.

While some patients report improvement, in my case it turned out to be counterproductive and lowered my sound tolerance dramatically. I never recovered from that worsening. I did this treatment with Pawel Jastreboff, Ph.D., the inventor of TRT himself, who couldn’t explain my results.

In more recent years, the availability of patient support discussion forums has grown. Now, with reports from many more patients, the consensus seems to be that TRT should be considered cautiously, and probably avoided, for all but the mildest cases of hyperacusis. Even then, TRT doesn’t account for the real-world noise environment or the problem of unexpected noise that can make tinnitus and hyperacusis worse.

A year after discontinuing TRT, I underwent a surgical clinical trial for hyperacusis called round window reinforcement. This surgery functions in some ways as a permanent earplug, building up a layer of tissue to dampen incoming sound. Though some patients reported improvement, unfortunately I was not one of them.

What’s more, it was strenuous to take a trip out of state for this surgery and stay overnight for a week. When I was entering the hotel they were vacuuming the lobby, which caused ear pain as soon as I walked in. I pleaded with them to stop until after I checked in, which they kindly did. And after all that time, effort, and expense of the surgery, I detected no improvement.

With the failures of the TRT and surgery, there remained little else to try. A year after surgery, as a shot in the dark, I tried a stem cell transplant, which did not help either, but at least it did not make things worse.

A Severe Case

Patients have taken to using “noxacusis” to describe severe cases which involve pain, and to differentiate themselves from more garden-variety loudness hyperacusis. This term was coined by Paul Fuchs, Ph.D., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who discovered nerve cells in the ear that previously were thought not to exist. Mild cases behave differently from severe cases, though they can turn into severe cases with more noise exposure.

The old way of thinking is that there is one kind of hyperacusis, where everything sounds louder. Fortunately, science has progressed, and it’s now known that there is a more severe form, pain hyperacusis, where loudness passes some threshold and turns into actual pain. And that pain lingers and worsens. It’s impossible to describe how much suffering this condition entails.

This wretched ear condition has affected every aspect of my life. It’s hard to imagine a worse disease. It’s invisible and untreatable, with no objective tests and lots of misinformation in the medical community. I was forced to stop working because the normal, everyday sounds of being in an office caused me ear pain. The simplest of things—a door slamming, a phone ringing, a shrill voice, even the crackle of paper when opening mail or turning a page—sends a stabbing pain through my ears.

I was forced to discontinue volunteer roles with my university alumni association and my homeowners association. I couldn’t participate in telephone conference calls or meetings, both of which involve endless ordinary sounds that are painful for me.

I can’t go to a restaurant—silverware clinking on dishes, music, even just the noise of people talking all cause pain. So I always eat at home, using plastic utensils and silicone dishes. I must leave for the day when construction in my apartment building is going on.

As my sound tolerance decreased, I was forced to stop everything that brought me joy. I used to be an avid tennis player and road runner, running 5ks, 10ks, and half marathons.

I live near Arlington National Cemetery, which has little vehicular traffic, so I can go on daily walks. These are almost safe. Still, I must be cautious because the bells of the clock tower gong every 15 minutes and the funerals of veterans meriting special honor involve gunfire.

Much of the advice available from clinicians and online about hyperacusis is that “everyday sounds cannot hurt you”; that you must “push your way through the pain” and “live your life.” I followed this terrible advice at first and unfortunately I found my ears got much worse. Almost any audible sound now causes pain—it feels like burning acid being poured into my ears, or a severe sunburn in my ear canals.

Sounds can also trigger lingering ear pain even in silence, which can last for days or weeks and is best described as a deep burning sensation. The chronic pain often comes with a delayed reaction, so I cannot always tell when a particularly painful sound will be injurious later.

As my hyperacusis worsened, tinnitus settled in. At first it was very mild and not bothersome. Then it would start to have short spikes where it would be loud and bothersome for an hour. As time went on, the spikes grew longer and the milder periods shorter, to the point where now it is severe almost all the time and intrusive.

The tinnitus has a number of sounds, most notably hissing and screeching. I can avoid ear pain from sound by being in quiet places, but there is no escape from the severe tinnitus.

So I am balancing both conditions. While earplugs and earmuffs temporarily make my tinnitus much more severe, they have also been a lifesaver to keep my hyperacusis from worsening. I have a pair of protective earmuffs in every room, plus in the car, so they are always at hand.

The Power of Science

Historically there has been much medical information that later was wholly discredited—for example the practice of bleeding. George Washington is perhaps the most famous patient—doctors removed 40 percent of his blood in an attempt to reduce fever and inflammation, and then he died. There were also lobotomies in the 1940s and 1950s—the inventor won a Nobel Prize—and the use of thalidomide in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which led to monstrous birth defects.

These examples seem outdated and unsophisticated now that we know better, but the principle holds. The audiogram may show what the ear can hear, but not whether language can be understood. We have learned that the synapses linking the ear and brain play a huge role in “hidden” hearing loss, which is responsible for difficulty understanding speech amid noise. A gene mutation for susceptibility to hyperacusis was identified in a research paper published earlier this year.

Research is essential. I learned about Hearing Health Foundation through Bryan Pollard, the late founder of Hyperacusis Research. In partnership with HHF, Hyperacusis Research raises money to fund biological research to find a cure, and HHF awards research grants through its competitive Emerging Research Grants program.

I helped Bryan in his work by raising money through Facebook fundraisers and publishing an annual newsletter for donors. In addition, I lead patient support groups, including global Facebook support groups with several thousand members, and a regional support group for tinnitus and hyperacusis sufferers.

Sadly, Bryan passed away after illness in 2022. Several patients and their relatives took over his work. I have joined the board of directors for Hyperacusis Research and I do as much as I can to assist in roles that do not worsen me. For example, I can answer occasional email inquiries from patients, but unfortunately I am not well enough to attend research conferences.

I spend as much time and energy as I can to further research for a cure, and hope I will see some breakthroughs in my lifetime. However, I know that the auditory system is a particularly complex part of the human body. The cochlea is the size of a pea, encased in hard bone, so it is impossible at present to do extensive research on living subjects.

I personally have signed up for the National Temporal Bone, Hearing, and Balance Pathology Resource Registry, which looks to better understand hearing and balance problems by analyzing donated human auditory systems. It is similar to being an organ donor, except that the donation of temporal bone after death helps scientists research better treatments and cures. I want to help future generations of patients long after I am gone. I know that HHF’s founder was instrumental in bringing regional temporal bone registries to the national level. The National Institutes of Health and Mass Eye and Ear now oversee the registry.

For all these reasons, I am making a planned gift to the Hearing Health Foundation. Hundreds of millions of people are affected by ear problems—not my rare pain hyperacusis, but hearing loss, tinnitus, aural fullness, and related conditions. Yet hearing research receives only a fraction of the funding spent on other diseases that affect large percentages of the population. I want to help make a difference, and I hope others will follow my example.

A Virginia resident, David Treworgy is a member of the board of directors for Hyperacusis Research. HHF is grateful to Treworgy for his support and to Hyperacusis Research for its support of our Emerging Research Grants program.

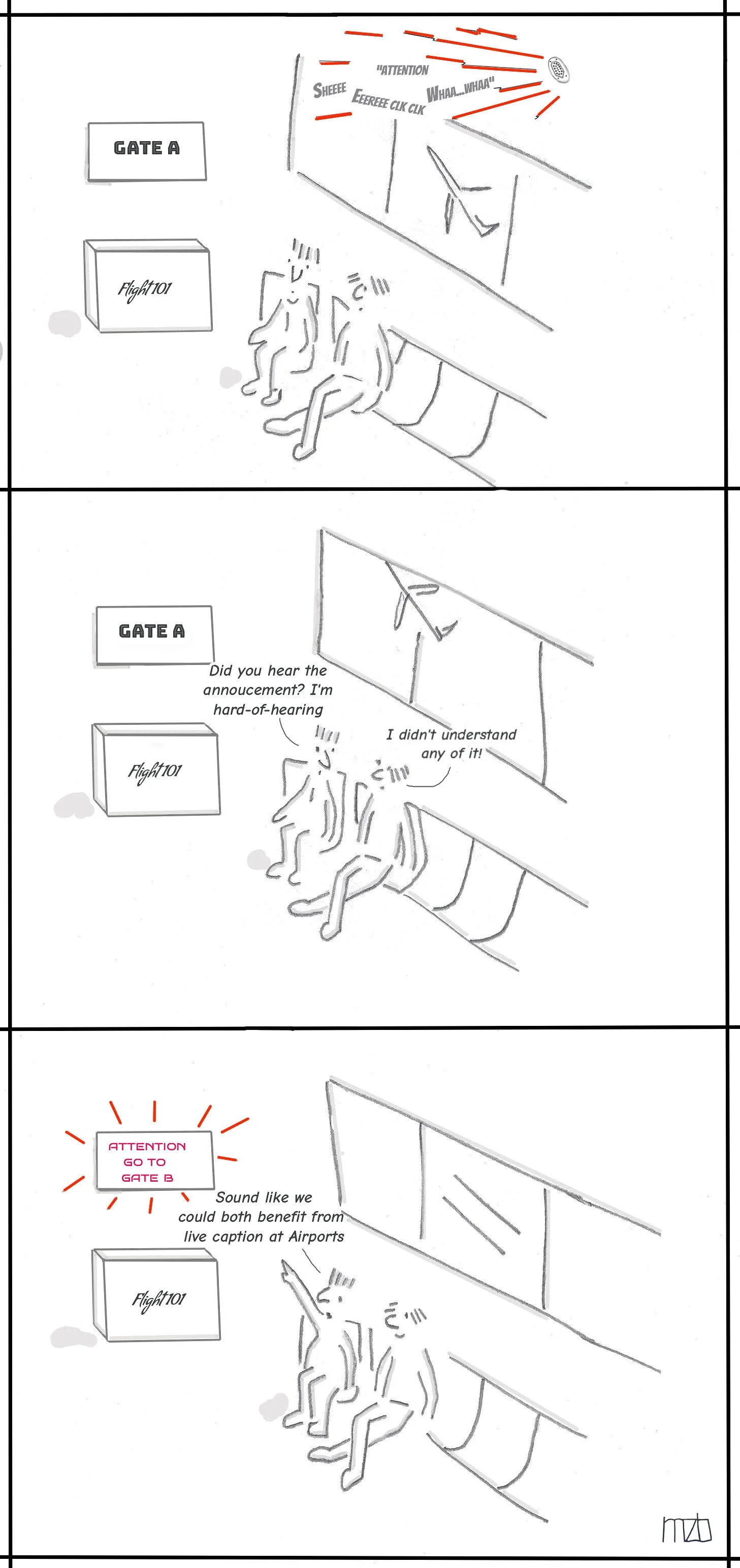

Our new public service announcement “Let’s Listen Smart” recognizes that life is loud—and it’s also fun. And the last thing we want to do is stop having fun! We just need to listen responsibly.