By Stephen O. Frazier

Google Maps has recently begun including hearing loops in the accessibility information on its website. This has received little notice from the national media or hearing loss–related entities but, for the hard of hearing, this is important news. A national database of looped venues has been a goal of hearing loop advocates for years and it's finally becoming a reality. This action, a joint undertaking of the Get in the Hearing Loop Committee (GITHL) of the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) and Google Maps, is the latest example of the growing awareness and availability of hearing loops in public places.

Hearing loops are the preferred assistive listening technology for those people with hearing loss and hearing aids. Unlike Bluetooth, currently a 1-to-1 means of transmitting sound, hearing loops can serve an audience of 1 to 1,000 or more. Hearing loops, in their simplest form, are a thin copper wire discreetly placed to encircle a room and are connected through an amplifier to the room's public address system.

The amplifier feeds the sound from the public address (PA) system to the loop wire that then transmits it as a silent electromagnetic signal to receivers in hearing aids. These receivers are called telecoils and they are available in the majority of hearing aids and all cochlear implant processors.

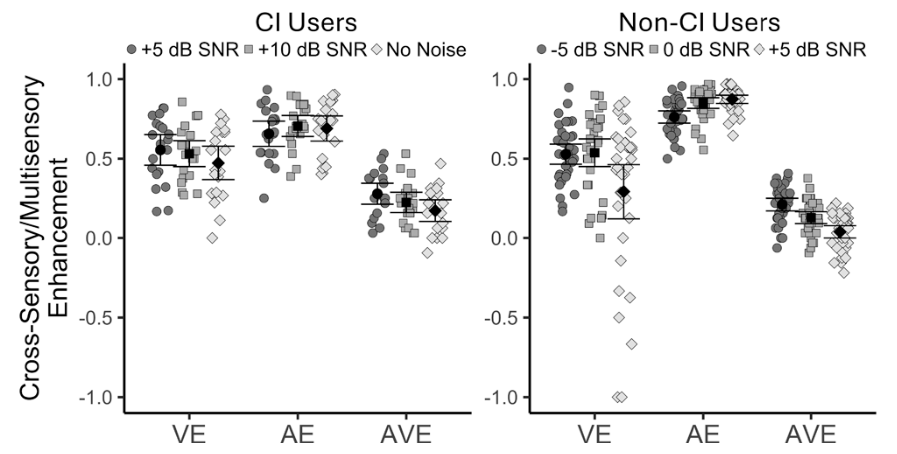

These hearing devices turn the signal back into sound and, with the microphones in the hearing aids or implant turned off, the user hears mostly the sound from the PA with little background noise. This dramatically increases the intelligibility of what is being said over the PA system. The “speech to noise ratio” that's so important in hearing and understanding conversation is heavily weighted to speech as opposed to noise.

Click on the > arrow on the bottom right of this image to get accessibility information.

User-friendly hearing loops are common in the U.K., much of Western Europe and Australasia and, in the U.S., increasingly found in theaters, places of worship, and other areas where people with hearing loss can expect to have difficulty hearing. I recently wrote about hearing loop efforts in the Summer 2022 issue of Hearing Health magazine.

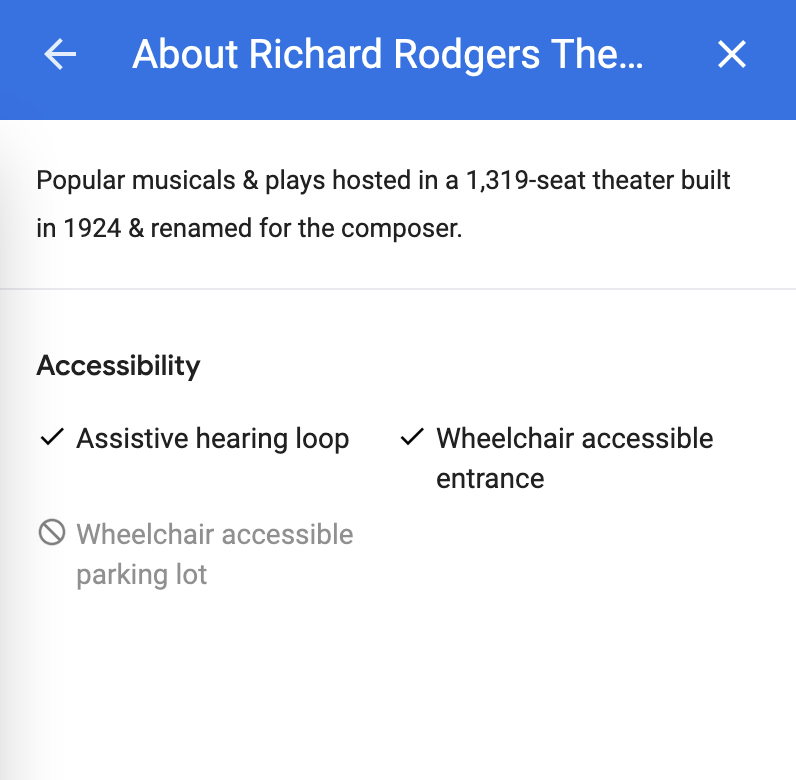

After clicking the > arrow this is the accessibility information displayed. Google Maps users can suggest edits and corrections.

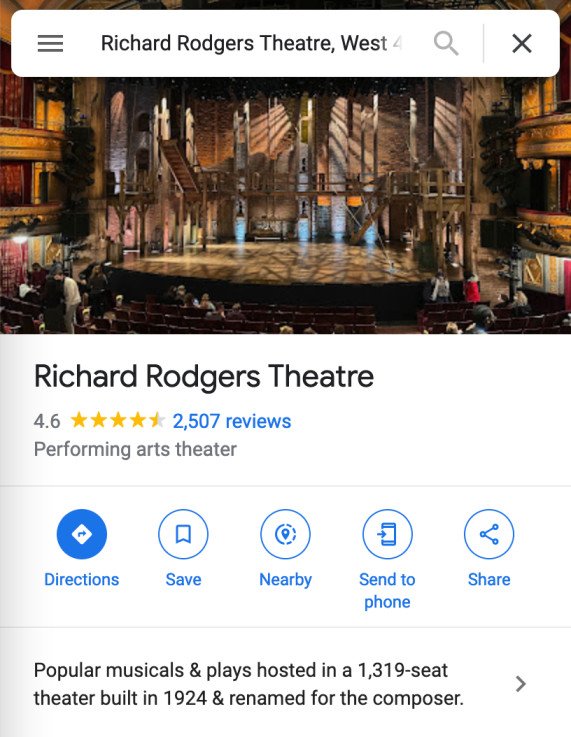

This initiative by the GITHL committee and Google Maps has already resulted in the listing of thousands of venues nationwide that offer hearing loop access. The process is ongoing. To check if a particular venue offers hearing loop communication access, visit maps.google.com on your laptop, tablet, or phone. Search the name of a venue, such as “Richard Rodgers Theatre New York City” and the map reloads showing the venue on a street map. A box contains information such as the venue’s street address, phone number, hours of operation, etc.

In that space, directly below a row of blue circular icons, is a brief description of the venue with a "more arrow” like this > (see images).

Click on that > arrow and you'll find "Assistive hearing loop" if one is known to be present, plus other applicable accessibility information such as wheelchair access or other accommodations. On a smartphone or tablet, this information is found on Google Maps by clicking "About."

This is an ongoing project and the GITHL committee continues to seek out and verify hearing loop installations throughout the country. The listings are interactive so individuals can lend a hand in maintaining their integrity.

On every venue's Google Maps listing there is a “suggest an edit” or a prompt to "update this place." There are also links to add a photo or to post a review. If mention of the loop is missing on a venue known to be looped, users can email the GITHL committee at loop.locations@hearingloss.org to let them know.

Loop installers or others involved with setting up hearing loss can suggest additions or revisions of Google Maps listings by visiting the HLAA’s site at hearingloss.org/hearinglooplocations and completing a brief form.

Trained by the HLAA as a hearing loss support specialist, Hearing Health magazine staff writer and New Mexico resident Stephen O. Frazier has served HLAA and others at the local, state, and national levels as a volunteer in their efforts to improve communication access for people with hearing loss. For more, see loopnm.com or email him at hlaanm@juno.com. For more information on this joint initiative, email GITHLinfo@hearingloss.org.

It bears repeating: What improves access for a group with a specific disability invariably also helps the greater population.