By Jayne Sowers, Ed.D.

1980, Atlanta. “Can you help us? Our 2-year-old has huge tantrums. She throws plates of food, she screams and yells. She doesn’t talk yet. We really need help!”

1977, Chicago. “I’ve been working with these 12-year-olds for two years. I know they are deaf, but why aren’t they learning to read?”

1976, Portland, Oregon. “The 4-year-olds in my preschool class for the deaf are doing well—they are picking up language better than the kids who are deaf who didn’t start school until they were 6. Why is that?”

These were the questions being raised by teachers of the deaf in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

In the early 1970s, only a few college programs for training teachers of the deaf existed in the U.S. Student teaching and practicums occurred at the states’ residential schools for the deaf. Rarely did public schools accept students with disabilities, including those who were deaf. Hearing aids were “body aids”—boxlike contraptions measuring 3 by 5 inches and strapped around the chest. Any neurological understanding of hearing loss in young children was in its infancy.

Teachers, parents, audiologists, and doctors sought answers on what and how children with hearing loss could hear, using any hearing that remained to learn the English language.

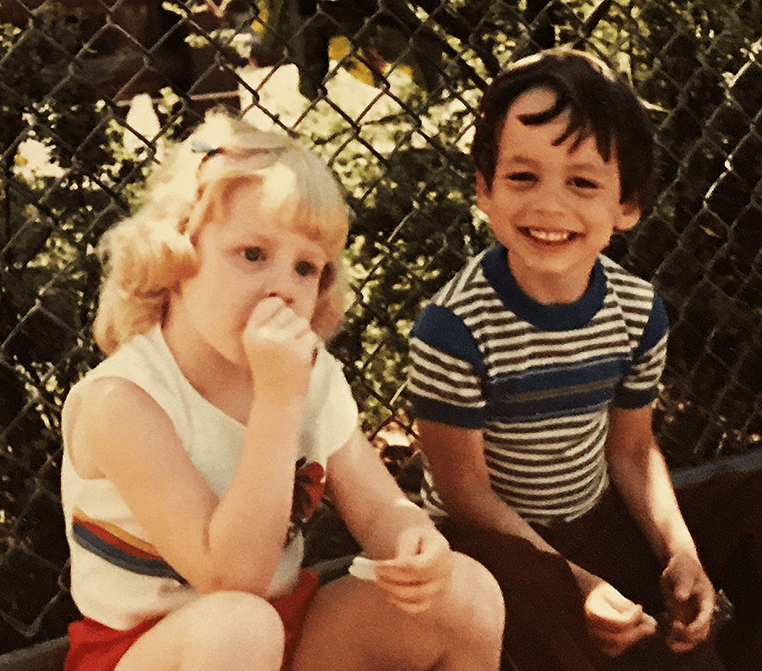

Jayne Sowers with two of the kids she taught—Katie and Bonnie—all dressed up for Graduation Day. This day was always in August, when the children turned 5 and could enter public school kindergarten. Without Infant Hearing Resource (IHR) they would not have had access to any early intervention.

In 1971 in Portland, Oregon, teachers of the deaf Nancy Rushmer and Valerie Schuyler—working with key stakeholders comprising physicians, audiologists, and community members—established Infant Hearing Resource (IHR). The purpose of the nonprofit was to address the needs of children with hearing loss so those children could develop language skills well before they reached school age.

Rushmer and Schuyler asked themselves: What would the new program look like? What age would the students be? They knew babies and toddlers would be too young to be in a school all day.

They concluded that the answer lay with the child’s family. The IHR program would focus on the parents as the child’s first and best teacher—a new approach and a critical change in educational practices.

With the instructional philosophy decided, the curriculum and instruction came next. IHR established these key program components:

A family/parent approach with specialists modeling and then coaching parents, siblings, and others in using play-based activities and daily routines through which the infant/toddler would learn to communicate.

A “whole-child approach” integrating cognitive, language, social-emotional, and physical development.

The use of auditory, receptive, and expressive language goals and lessons for the child with hearing loss that follow the same developmental milestones as their hearing peers.

A recognition of and provisions for families encountering the stages of grief upon learning their young child has a hearing loss.

An emphasis on collaboration with other specialists for children with syndromes and multiple disabilities.

After two years of implementing these key components, the educators found that their program was viable: All 12 children with hearing loss, from infants to age 4, made significant progress in all areas of development.

Sharing the Success

The success of the young learners through the use of language-based, developmentally appropriate practices showed the IHR staff that the younger the child with hearing loss, the better and faster they could learn—a new and amazing discovery. The IHR approach was working.

Two teachers of the deaf established IHR to address the needs of children with hearing loss so they could develop language skills well before they reached school age.

The next step was to share their program more widely. In 1976, the U.S. Department of Education offered nationwide funding opportunities to a few selected programs that were currently working with families of infants and toddlers with hearing loss. IHR was one of the six selected programs. The first of several three-year federal grants provided for IHR staff to train specialists who would then teach families of infants and toddlers with hearing loss.

IHR staff interviewed applicants from across the U.S. who were teachers of the deaf or audiologists. Each year six were selected to enroll in the nine-month program. Working alongside IHR staff, the trainees learned proven techniques for teaching young children with hearing loss, eventually earning a university certificate: “Parent-Infant Specialist: Hearing Impaired.”

Learning as a Family

I was a teacher of the deaf in Atlanta in 1979, and the first very young child I worked with was Alison, age 2, whose parents needed help with her unruly behavior. Bubbly and nonverbal, Alison entered the audiology suite with me where a clapping monkey (then a state-of-the-art method to validate conditioned responses in young children) verified Alison’s hearing loss. Her lack of or intermittent responses helped explain her challenging behavior.

As her parents watched through the window, I could understand their mixed emotions: “Oh no—our baby cannot hear! But we finally have an answer to why she acts like she does.” The audiogram showed a sloping bilateral, moderate-to-severe hearing loss, indicating Alison could hear only about half of the words spoken to her. A few weeks later, as the audiologist placed the hearing aids in Alison’s ears, her eyes widened and her smile broadened as she heard the sound of her mother’s voice for the first time.

We met three afternoons a week to help Alison and her family learn how to use her hearing aids and develop her oral language, and she made excellent progress. When her hearing loss was first identified at age 2, her speech and language were at the level of a 9-month-old. But after two years of child-based, interactive lessons, Alison caught up to her hearing peers. By the time she was 5, the public schools were ready for her and she was ready for them. She succeeded orally without the need for sign language—thanks not only to her residual hearing but also to early fitting of her hearing aids and her auditory and language training.

With the success of this one child, I sought out additional education to advance my skills for teaching young children with hearing loss. I was selected to train at IHR in 1981, eventually joining the staff.

Hearing and Balance

In the early 1980s IHR worked closely with nearby institutions Good Samaritan Hospital and Oregon Health & Sciences University. Doctors and researchers were studying the relationship of sensorineural (inner ear) hearing loss to the vestibular (balance) system in young children.

This was good news for 2-year-old Katie, my second young client. Her mother said she seemed to hear only intermittently, but this did not concern their family physician. After months of searching, Katie’s mother found an audiologist who tested infants and toddlers, which in turn led her to IHR.

When she turned 4, Katie (left) transitioned smoothly to her peers’ classroom for the hearing impaired in the public schools.

Several visits to the audiologist revealed a severe bilateral hearing loss. But Katie’s mom voiced concern about Katie sometimes stumbling or weaving while walking. Frequent hearing tests determined Katie’s hearing loss was worsening over time.

Back then, the connection between hearing and balance was starting to be uncovered. William House, DDS, M.D., was pursuing the first surgical treatment for debilitating vertigo, often a symptom in Ménière’s disease, and he later developed the first cochlear implant.

Despite her bouts of imbalance and nausea, Katie and her family regularly attended IHR three times a week. Due to Katie’s progressive hearing loss, her parents opted for the addition of sign language to the lessons. Three months later, at age 2 1/2, Katie signed “water” and uttered “wa-wa” as her first word as we poured pitchers of water into a baby bathtub. It was a tearful moment for all in the room.

Katie learned new signs daily. They provided a necessary bridge for her to communicate her wants and needs and to understand what was being requested of her. Our IHR home visits accommodated evenings where grandparents, neighbors, and playmates could learn sign language as well. When she turned 4, Katie transitioned smoothly to her peers’ classroom for the hearing impaired in the public schools.

Changing Views

With these successes, why weren’t children like Alison and Katie identified as having a hearing loss much earlier in age? Mostly we just didn’t have the research-backed knowledge like we do now.

Up until the early ’80s, research on infant brain development was minimal. The role of early brain stimulation was unknown. The term “early intervention” did not yet exist—in fact, not until 1986 did the term exist, when it became part of Public Law 99-457, an extension of the 1975 Public Law 94-142 Education for All Handicapped Children Act. The new law for the first time specifically addressed infants to 4-year-old children, stating that public schools must provide “early intervention for infants and toddlers with disabilities”—15 years after IHR opened its doors.

A second reason was the family practitioner’s understanding of infant and toddler hearing development. Educators of the deaf and audiologists repeatedly heard from parents of newly identified 2- and 3-year-old toddlers with hearing loss that their family doctor had “tested” the child and declared that the hearing was typical.

This led IHR to work with Oregon Health & Sciences University to train family physicians to conduct proper hearing tests. For each new class of residents, IHR staff demonstrated how not to do a screening. Doctors learned that slamming a door creates vibrations the child can feel so they turn toward the “sound”; by ringing a bell behind a child, the doctor may cast a shadow visible to the child; and hitting a tuning fork may be visible within the child’s peripheral vision.

By the 1980s, groups formed across the U.S. to demand that formal hearing screening of children occur much earlier than was required—in first grade. In 1993, the National Institutes for Health recommended universal hearing screening of all newborns. By 1999, most states passed legislation for mandatory newborn hearing screening before the infant was released from the hospital.

IHR specialists modeled and coached families on play-based activities and daily routines to foster communication with their child.

IHR along with many organizations like Hearing Health Foundation advocated for universal newborn hearing screening. This work continues today, as seven states still lack screening legislation and 35 percent of states that do have screening laws do not require screening all newborns.

Identifying Infants

Revolutionary changes in legislation and technology continue to improve the lives of children with hearing loss and their families. In the past few decades, we have seen auditory brainstem response testing for infants; cochlear implants; IDEA (Individuals With Disabilities Education Act) requiring public schools to serve children with disabilities from birth through age 21; closed captioning; automated speech translation; powerful wireless hearing aids; cochlear implants including for patients at age 9 months; and specially trained early intervention teachers.

The passage of IDEA in 1975 served as a turning point for children with disabilities, especially those ages 0 to 4, as local public school districts began to provide services rather than depending on small, nonprofit agencies. These programs reflected the proven instructional practices and methods developed by IHR and related groups.

As for the two young learners above, I am still in touch with both. Through Zoom and Microsoft Teams (current examples of how technology allows for accessibility), I was able to catch up with them in hours-long conversations. One uses speech-reading and the other American Sign Language and speechreading to foster communication.

Alison completed her college degree and has worked for many years as an accountant at the Jimmy Carter Center in Atlanta. She and her husband have two girls. Katie received a master’s degree and works as a teacher of special education at a residential school for the deaf and with her husband, operates a house for adults who are deaf and have medical issues. They are raising two young boys.

Alison and Katie represent the first cadre of truly “young” children with hearing loss to receive an early education, which is now known as a critical time of language and communication development. These children gained the academic knowledge and social practices to move seamlessly between the hearing and deaf worlds, and are making valuable contributions to their communities.

And IHR? With the IDEA amended in 2004, the bar was raised for local schools to provide services for children from infants to age 21 so the need for other private agencies was no longer needed. IHR closed its doors. Its work was done.

Opportunities for young children with hearing loss came about because a small group of pioneers advocated for young children, realizing the needs of the whole family, raising private funds to maintain their programs, and working in cooperation with both the medical and social-emotional fields. Let us take a minute to acknowledge and appreciate those teachers of the deaf and audiologists who believed that young children with hearing loss should and could be taught from birth in their family environment, just like their hearing peers.

Among the first few dozen Infant Hearing Resource specialists, Jayne Sowers, Ed.D., is an educational consultant and lives in Indiana. She sincerely thanks Valerie Schuyler, who founded IHR with Nancy Rushmer, for help with this article, which also appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of Hearing Health Magazine.

I’ve been collecting these anecdotes that I hope help those of us living with hearing loss to remember that laughter can be the best medicine